SINCE MARCH 2020, I’ve interviewed dozens of LGBT people via Zoom to talk about their experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic for a full-length documentary, Attend Me: A Pandemic Journal, from Outspoken Films. Also, I’ve been making images and filming coronavirus-related street art in the Las Vegas Arts District known as “18b,” an eighteen-block, rundown corridor with recent small-business gentrification, where street artists painted murals. In Poetry and Commitment, Adrienne Rich wrote about the role of artists as fundamental to resistance movements:

But—let’s never discount it—within every official, statistical, designated nation, there breathes another nation: of unappointed, unappeased, unacknowledged clusters of people who daily, with fierce imagination and tenacity, confront cruelties, exclusions, and indignities, signaling through those barriers—which are often literal cages—in poetry, music, street theater, murals, videos, Web sites—and through many forms of direct activism.

§

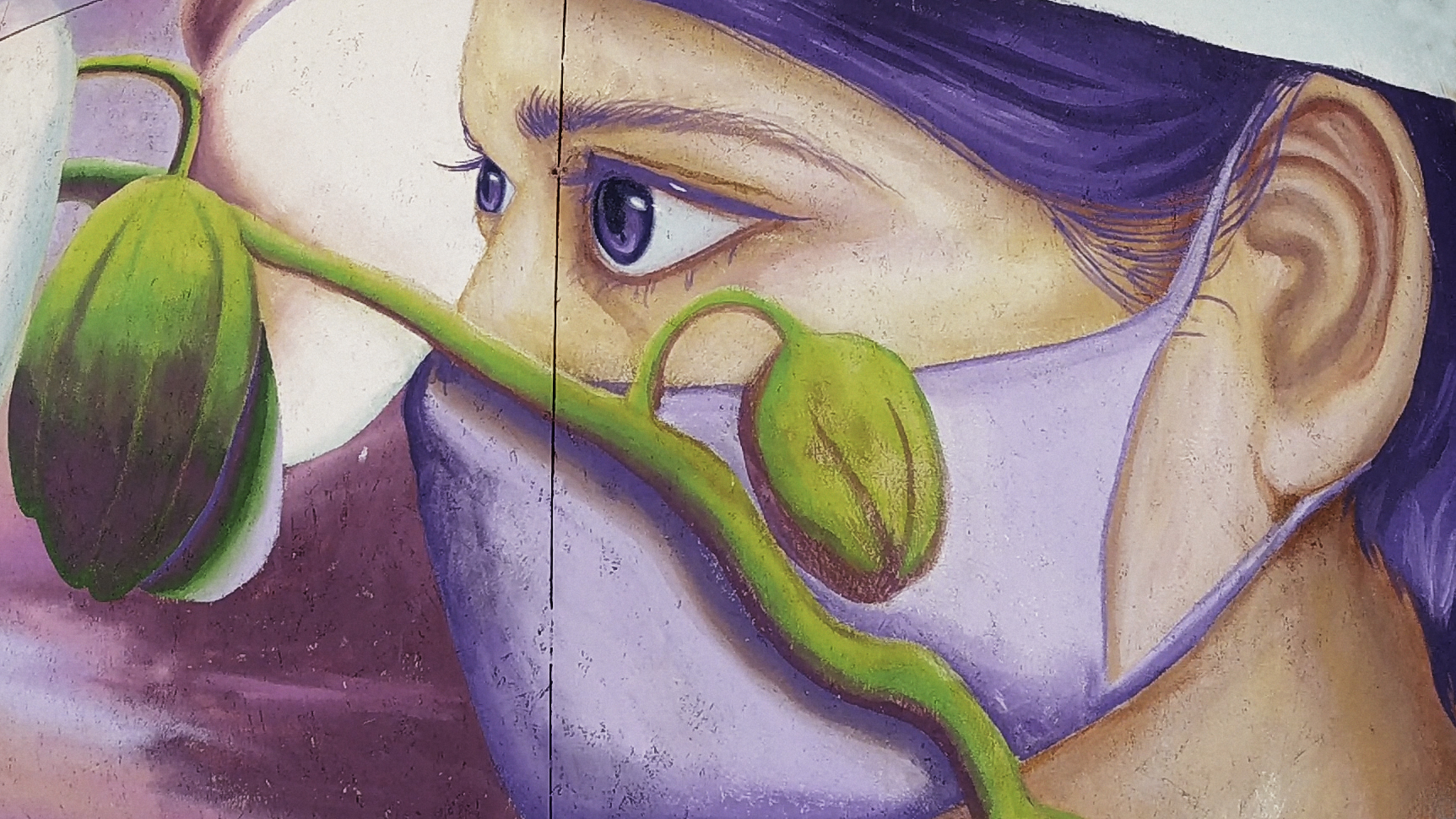

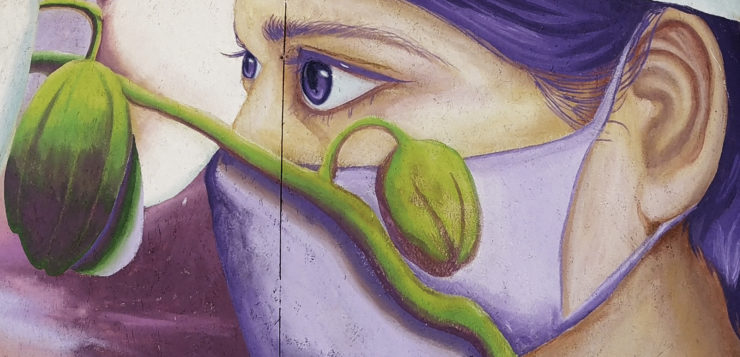

Around the world, masks have been the one recurring metaphor to symbolize the Covid-19 pandemic. Historically, masks serve a social function and can be used in communal rituals to promote the cohesion and the well-being of a community, as protection from evil spirits, or to ward off sickness. Often in poetry a mask trope alludes to disguise, secrecy, and maintaining hidden identities.

In 1896, African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote “We Wear the Mask” with the lines: “We wear the mask that grins and lies/ It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,” expressing the sadness of concealing one’s authentic self. A century later, the hip-hop group the Fugees referenced the Dunbar lines in the song “The Mask”: “Put the mask upon the face just to make the next day/ Feds be hawking me, jokers be stalking me/ I walk the streets and camouflage my identity.” Mental health counselor and author Irene Javors of Jackson Heights, NY, writes in her poem “Pandemic–Gotham Weeps”: “We are ordered to wear masks/ So familiar/ To a lesbian/ Living in the patriarchy/ Life has always been a masquerade/ Of camouflaged desires.” The mask can refer to being closeted, disguised behind a false identity. During the Covid pandemic, masks have been politicized, as condoms were by abstinence-only homophobic religious activists during the AIDS plague.

Macabre actor Vincent Price and low-budget filmmaker Roger Corman adapted a short story by Edgar Allan Poe into the 1964 apocalyptic, spine-chilling, cult-classic The Masque of the Red Death. Prince Prospero, the mythical central character, “retired to the deep seclusion” within a walled and iron-gated abbey to escape a plague ravaging his country after “his dominions were half depopulated.” But the Red Death was inescapable. At an orgiastic celebration, “he had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revelers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel and died each in the despairing posture of his fall.” Of the government’s failure to respond effectively to the devastating coronavirus pandemic, Bronx, NY, poet and writer Perry Brass writes in “Covid-19,” dedicated to Kious Kelly, a gay nurse who died of the coronavirus: “They had put their political/ morons in charge, when you started/ to have dreams of doves/ and angels, of your rescue, of/ certainty, to keep away those nightmares of ghouls hiding/ inside acts of everyday normalcy.” Some of the people I interviewed had contracted Covid-19 and were recovering from its effects, including the following dissimilar accounts—one a homebound person and the other someone out in the world. The former was an early LGBT activist, Bruce Gottfried of Yonkers, New York, for whom being shut in was not a new experience. He has multiple sclerosis (MS) and uses a wheelchair and receives visits from three home-health aides. He didn’t expect to contract Covid-19, but he did, and was hospitalized for eight days and in a nursing home for two weeks before returning home. “I’m terrified of the second wave of Covid-19. I’m certain there’s going to be a second wave. I don’t know if I’m immune or not. I’ve not been retested.” The second interview was an associate professor, Harlem Gunness of South Orange, New Jersey, who reported: Two weeks into the pandemic, my husband John flew home … he started to exhibit mild symptoms of the coronavirus. He was in isolation for three weeks until all symptoms went away. We were fortunate enough to have a dedicated room and bathroom. We had to be very strict about it because we have two six-year-old daughters. It was very difficult because the girls’ school closed, and they had to be home-schooled. I was juggling my responsibilities at work, taking care of John and my children’s remote learning from many different websites. § As for the U.S. government’s response to the pandemic, let me cite three essential books that chronicle the assault on secular government by Christian nationalism—Jeff Sharlet’s C Street (2011), Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains (2018), and Katherine Stewart’s The Power Worshippers (2020)—all of which prognosticate the spectacle that is the Coronavirus Task Force, whose official mission it is to monitor, prevent, and mitigate the coronavirus pandemic, but whose members are mostly self-congratulatory Christian nationalists who seem to revel in the pandemic’s spread. Most of the Task Force’s members are driven more by religion than by science and have been fierce opponents of reproductive healthcare and LGBT rights. For example, Surgeon General Jerome Adams proclaimed: “I really do think God always has a plan.” Alex Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), established a division of Conscience and Religious Freedom, authorizing healthcare pro-viders to refuse to perform medical services if they violated their moral conscience. Doctors Deborah Birx and Robert Redfield are evangelical Christians who served on the board of the Children’s AIDS Fund (CAF), whose founder Anita Smith lobbies for abstinence-only sex education around the world. Smith once said: “What we have here is a power struggle between [us and]homosexual white men who abuse all the government AIDS programs fundamentally to fund their subculture and their political activities.” Ben Carson, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), is a cabinet sponsor of Capitol Ministries, which provides Bible studies, evangelism, and discipleship to political leaders. Vice President Mike Pence, who chairs the Task Force, falsely claimed that the U.S. had “flattened the curve” even as hospitalizations, new cases, and mortality were spiraling out of control. Anthony Fauci is an exception to the religious activism of the Coronavirus Task Force, though he had an uneven history with the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, as described by Randy Shilts in And the Band Played On. In 1983, Fauci wrote an “infamous JAMA editorial” proposing that HIV could be transmitted through “routine personal contact among family members in a household.” He was called an “imbecile” by Larry Kramer in Reports from the Holocaust, but the former adversary became a friend when Fauci made life-saving changes to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). As with AIDS in the 1980s, the Covid-19 pandemic has spawned opportunism, deception, and the proliferation of false, potentially harmful treatments. In the U.S., there is fear-mongering from the anti-vaccine (anti-vax) movement, which claims that vaccines cause autism and de-masculinization. Amid FDA warnings against using hydroxychloroquine outside of hospital settings because of the risk of serious heart events, Donald Trump said: “A couple of weeks ago, I started taking it, because I think it’s good. I’ve heard a lot of good stories. And if it’s not good, I’ll tell you, right? You know, I’m not going to get hurt by it.” At a televised meeting of the Coronavirus Task Force, he mused about disinfectants: “I see the disinfectant where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning?” The notorious Alex Jones of InfoWars claimed: “The government is using chemicals to turn people gay. So-called ‘estrogen mimickers’ are being placed in juice boxes, water bottles, and tap water to ‘feminize’ people.’” He was warned by the FDA to stop selling false Covid-19 cures. § For the LGBT community, the AIDS pandemic initiated profound behavioral changes in sexuality, particularly before pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The complexities of behavioral change and safer-sex practices are substantially more extensive and challenging than wearing a mask. At the most basic level, there was condom use and non-penetrative sex without the exchange of bodily fluids. However, there were many innovative strategies—phone sex and on-line chat rooms—and some can be instructive for the Covid pandemic. Apps such as Grindr, Tinder, Bumble, Scruff, and Jack’d advise users to follow CDC guidelines but stopped short of advising users against in-person hookups. Theater artist and social activist Joan Lipkin of St. Louis, Missouri, contemplating the current health crisis, remarked: It took me back to some early roots and it gave me the opportunity to think about some things. The role of moral leadership that some of our queer compatriots took during the AIDS epidemic. The way they uncovered the tension between the American tradition of individualism and collective need. I decided to take a look at How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, by Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen. For us to observe appropriate medical protocol is a reflection of love. Associate dean Barclay Barrios of Wilton Manors, Florida, commented: I’m a very strong introvert. I’d go out to the leather bar and sort of hang with people. I’d have dinner with friends. That’s all not exactly gone, but it’s been replicated in ways that feel like a shadow of their former selves. … I just left a virtual cigar social, which is not the same, but it’s something. At the cigar social I was at people were comparing it to the AIDS epidemic. It was very clearly a kind of PTSD. And a guy from Los Angeles talked about how the community immediately started gathering resources because we’ve learned we can’t trust the government to take care of us. In most major U.S. cities, LGBT centers provide vital social services, often to marginalized populations. They serve as community venues for numerous events and conduct meetings for twelve-step programs and support groups. They have been closed for many months with only remote services. Transgender activist Frankie Perez of Las Vegas spoke of the criticality of LGBT centers: “Not being able to access the LGBT center. Access to the Internet. Not being able to be just themselves. The Las Vegas Lounge, transgender owned and operated, was a safe haven for transgender. It couldn’t survive financially during state-mandated closure.” Wearing T-shirts with the slogan “Asylum is an lgbtq Issue,” transgender activist Ellen Holzman and her spouse Meredith Vezina of San Diego agree that Covid is hitting marginalized people the hardest. Ellen expressed her concern: “The two transwomen we have living with us before the coronavirus were just starting to get stable. They were both working, and all of a sudden the coronavirus comes, and they lose their jobs. And they have no money.” Meredith wrote in the Sdglbt News: “Most transgender women who request asylum do not have the support of their biological families. So unlike cis asylum seekers who have relatives in the U.S., trans women languish in detention because there are no relatives willing to help them.” § Susan Sontag remarked in AIDS and Its Metaphors (1988): “The AIDS epidemic serves as an ideal projection for First World political paranoia. Not only is the so-called AIDS virus the quintessential invader from the third world. It can stand for any mythological menace.” The Covid pandemic has seen incidences of racism, homophobia, and xenophobia stoked by Donald Trump, who said the following at the West Point graduation ceremony: “The new virus that came to our shores from a distant land called China. We will vanquish the virus. We will extinguish this plague.” At his notorious rally in Tulsa, he declared: “By the way, it’s a disease without question, has more names than any disease in history. I can name ‘Kung flu.’” Themes about social separation, isolation, anxiety, depression, and lethargy echoed throughout the narratives of interviewees. Edmund White told New York Times contributor Ted Loos: “I find most writers that I talk to can’t write during this thing. They just watch msnbc and sleep.” But many writers and artists are accustomed to solitude and the artistic process. Lesbian-feminist writer and activist Sue Katz of Boston read from a blog post titled “My One-Month Isolation Anniversary”: “Since I closed the door on March 11, I haven’t opened it again except to bring inside the things kind people deliver outside my door—either my mail or groceries or medicine; and except for my late-night journeys down the long empty hall of my apartment building to the garbage chute.” Poet Michael Joseph Arcangelini of Sebastopol, CA, writes about vigilance, vulnerability, and mortality in “Hour of the Wolf”: “He wants into my house./ Tries to sneak in on the soles of my shoes./ The surface of my hands./ He wants to settle down in front of the heater./ He wants food and drinks served to him./ He wants my life.” People spoke of loved ones from whom they are separated, stranded for months in other states or countries. Performance artist and professor Holly Hughes of Ann Arbor, whose partner Esther Newton was in Florida, asked: “How do you negotiate travel from Florida to Michigan with two dogs 1500 miles away?” Writer Dennis Altman of Melbourne, Australia, lamented: “On March 27 Juan Carlos sent me a video taken from his balcony, of police and military enforcing a curfew in Quito. … For the first time since we met, there can be no plans to see each other again. Global lockdowns have disrupted relationships in all sorts of ways, either forcing people apart or ironically forcing them too much together.” Undeniably, the coronavirus pandemic exposes pre-existing social inequities and discrimination with a disproportionate effect on people of color, indigenous people, and seniors in terms of hospitalizations, severity of symptoms, and mortality. There’s been an alarming rise in domestic violence with families in lockdown. LGBT people have higher rates of HIV and cancer and smoke tobacco at higher rates than the general public. Consequently, we are more susceptible to Covid-19 infection and can expect poorer outcomes. LGBT people also experience the lack of cultural competence within healthcare systems along with the narrowing of the legal definition of sex discrimination in the Affordable Care Act, omitting protection for transgender people. This is a consequential time in the history of the Republic with the intersection of two significant events. First, the global coronavirus pandemic is a seismic health crisis that has killed nearly 150,000 Americans as I write, with the number of new cases rising daily. Second, arriving on its heels are the civil uprisings and Black Lives Matter protests in every U.S. city in response to the police killings of people of color. These events compel an intersectional analysis because they focus on communities and social issues with often forbidden, outlawed, or concealed perspectives.