Delayed Rays of a Star

Delayed Rays of a Star

by Amanda Lee Koe

Doubleday. 383 pages, $27.95

WHO AMONG US has not wanted to see inside the lives of the most glamorous or intriguing stars of a bygone generation? In Amanda Lee Koe’s debut novel, Delayed Rays of a Star, we get to know three such stars: Marlene Dietrich, Leni Riefenstahl, and Anna May Wong. The novel’s first three chapters alternate between their stories, which are denoted by the symbols Koe uses to mark shifts between characters throughout the book.

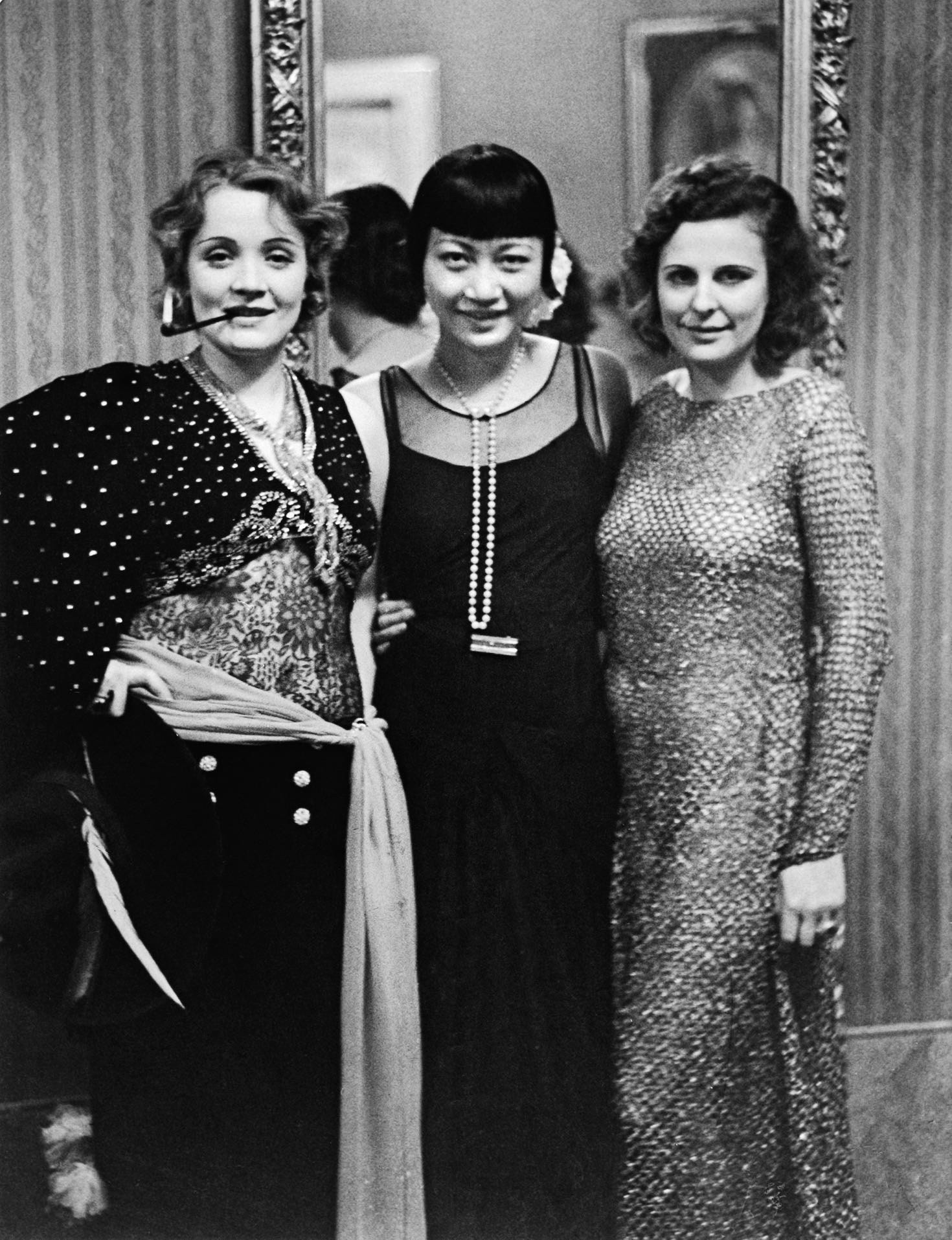

Their narratives first intersect at a party in Berlin, in 1928, when the novel begins. The action revolves around the photograph that inspired Koe’s book, which was actually taken in 1930, when the three women stood together and posed for a photographer. In Koe’s narrative, Dietrich then spills her drink on Wong’s dress, and in subsequent chapters the attempt to clean the dress leads to a brief sexual encounter in a bathroom. In these pages, Dietrich plays the expected roles: the vixen, the bisexual seductress with the charm to bed anyone she likes. Avid fans of Hollywood’s Golden Era will thrill to the accounts of Dietrich and Wong’s affair and how it colors their work on Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express. Movie buffs will enjoy teasing out the historical fact from fiction, which Koe weaves together so seamlessly that the question of what’s real and what isn’t ceases to matter as one reads deeper.

But the novel is not only, or even primarily, for those nostalgic fans looking to immerse themselves in a bygone era. At its heart, Delayed Rays of a Star is a close-up examination of the prejudices of an era through the lives of three of its most politically divisive female figures. Some readers may come to the novel unaware that Dietrich left her native Germany amid the rise of Hitler, denounced the Nazis, pursued U.S. citizenship, and gave performances to GIs fighting against Germany during World War II. Meanwhile, Leni Riefenstahl, who auditioned for the part that launched Dietrich to stardom (Lola Lola in 1930’s The Blue Angel), went on to become one of the most notorious, reviled directors of all time thanks to Adolf Hitler’s patronage and her role as the director of much Nazi propaganda, including Triumph of the Will (1935).

In the midst of this heavy Germanic influence, Anna May Wong’s narrative provides an alternate but no less political perspective, examining how Wong struggled against the inherent racism of Hollywood and the Hays Code in her pursuit of a career in the movies. Of the three women, Wong possesses the lowest degree of control over her range as an artist, having neither the benefits of superstardom nor the backing of a dictator to support her. Consequently, Wong was serially typecast, offered subservient roles, or passed over altogether. In the end, her narrative proves the most touching, as the dignity of her character isn’t undermined by the grotesqueries of old age or fascism, as it is for Dietrich and Riefenstahl, respectively.

Koe supplements the three primary narratives with subplots devoted to many—one might even say too many—secondary or tertiary characters, including Wong’s German philosopher pen pal Walter Benjamin; the best boy on the set of Riefenstahl’s Tiefland, Hans Haas; and Bébé, the Chinese maid who attends to an aging Dietrich in her final years as she languishes in bed in Paris, using a Limoges pitcher as a bedpan and dousing herself in perfume instead of bathing. In these side plots, the political intention of the novel becomes impossible to ignore, even for those readers who just want to read about old Hollywood and World War II. When Bébé’s half-German, half-Turkish boyfriend is shot by East German soldiers beside the Berlin Wall, or when Bébé herself is deported back to China after the shooting, Koe is commenting on the absurdity of the political regimes and tensions that dominated the second half of the 20th century.

It should come as no surprise that the novel ends when the Berlin Wall falls in 1989. Having dozed through most of the action, Dietrich watches the aftermath on TV in wonderment. It’s the beginning of a new era—one still haunted by images of the past. Koe’s novel is a rueful examination of the delayed impact that our collective and individual histories can have on the present.

____________________________________________________