AMONG the notable 20th-century painters, Cy Twombly is one of the most polarizing, either adored or despised by critics and the public, with few people in between. If his admirers consider him a poetic genius, his detractors claim that a child with a crayon could do as well. In 1993, Twombly was the subject of a 60 Minutes piece by Morley Safer titled “Yes, But Is it Art?”

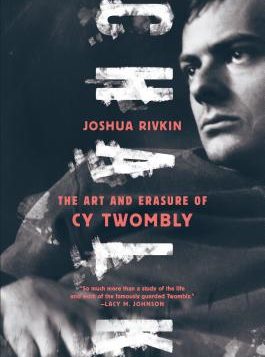

Joshua Rivkin’s new book on Twombly is unlikely to convert many skeptics, and since there are no reproductions in the book (for various reasons, he received virtually no cooperation from the Twombly Foundation), devoted fans will need to spend a lot of time Googling images that can’t come anywhere close to approximating the feel or texture of the actual canvases. On the other hand, for those who love his work, Chalk is a very welcome book. Not exactly a biography or an appraisal, it’s partly about how hard it is to write a book on someone as intensely private as Twombly was. It is also a rumination on what makes us respond to certain works of art and to certain artists.

“I use paint as an eraser,” Twombly remarked. “If I don’t like something, I just paint it out.” In Rivkin’s investigation, Twombly, who was gay, marked out many things in his life, the traces of which are often still tantalizingly available, if not quite understandable. Twombly and artist Robert Rauschenberg were lovers for a short time and maintained a friendship throughout their lives. For Rivkin, the theme of the departed lover resonates all the way from his earliest work through to his final masterpiece, Untitled: Say Goodbye, Catullus, To the Shores of Asia Minor. Rivkin cites a Twombly photo from early in their relationship called Bed—a counterpart to Rauschenberg’s famous work of the same name—which he describes as “crumpled sheets like topographical maps. One can feel the heat where the body, or bodies, had been.”

Not exactly secretive about his sexuality but not entirely open about it either, Twombly often inserted bits of poems or myths into his paintings about pairs of lovers, one or both of whom die. Rivkin also notes: “It’s hard to miss the same-sex desire in the texts and writers Twombly borrows. … The erotic life … that Twombly kept in mind or notebook, is decidedly queer.”

For fans, it’s the missing context that’s so evocative and intriguing. In poetry, as in painting, the fragmentary, the gestural, the hidden, and the outright erased can be just as evocative—if not more so—than what’s actually there. Indeed, this element is central to the appeal of Twombly’s canvases in that what’s been alluded to or elided provides an opportunity for our minds and imaginations to find meaning in the work. This is why we can engage so strongly with paintings such as Achilles Mourns the Death of Patroclus, with its abstract, floating clouds mimicking the essences of each; Woodland Glade, with its minimalist, penciled horizon line and splash of green suggesting a tree; or Coronation of Sesostris, with its impressionistic suggestion of an Egyptian barge. Indeed, once clued into the context, Twombly’s work can also be extremely moving. Rivkin cites a novelist who wrote: “I slumped into an empty corner opposite Say Goodbye, Catullus and wept into my knees for a half hour.”

For fans, it’s the missing context that’s so evocative and intriguing. In poetry, as in painting, the fragmentary, the gestural, the hidden, and the outright erased can be just as evocative—if not more so—than what’s actually there. Indeed, this element is central to the appeal of Twombly’s canvases in that what’s been alluded to or elided provides an opportunity for our minds and imaginations to find meaning in the work. This is why we can engage so strongly with paintings such as Achilles Mourns the Death of Patroclus, with its abstract, floating clouds mimicking the essences of each; Woodland Glade, with its minimalist, penciled horizon line and splash of green suggesting a tree; or Coronation of Sesostris, with its impressionistic suggestion of an Egyptian barge. Indeed, once clued into the context, Twombly’s work can also be extremely moving. Rivkin cites a novelist who wrote: “I slumped into an empty corner opposite Say Goodbye, Catullus and wept into my knees for a half hour.”

None of this is likely to convince those who just don’t connect with Twombly’s work, but it will resonate for those who do. Indeed, chasing down his work has become something of an obsession for many of his devotees, of which I now count myself as one. At times the author can seem a little too much in love with his own searching, but he never really lets us in on the secret of what he personally finds so fascinating about this artist. Still, if this book were nothing more than a summation of some of the most interesting things ever written about Twombly, that would be enough to recommend it. Yet Chalk is also a sensitive and thought-provoking look into the mind of an extremely important figure and even confronts the question of whether an artist’s sexuality is important to his or her work. From the evidence of this book, that is certainly a key question that needs to be addressed in order to understand this, or any, artist’s meanings.

Dale Boyer is the author of The Dandelion Cloud and Thornton Stories. A new work, Justin and the Magic Stone, is forthcoming.