Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989

Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989

Grey Art Gallery and the Leslie-Lohman

Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art , NYC

April 24-July 21, 2019

Catalog published by Rizzoli. 304 pages, $60.

We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power, and Pride

We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power, and Pride

in the History of Queer Liberation

by Matthew Riemer & Leighton Brown

Ten Speed Press. 368 pages, $40.

Dona Ann McAdams: Performative Acts

Brattleboro Museum and Art Center

June 22-September 23, 2019

Catalogue published by Brattleboro Museum

and Art Center. 60 pages, $15.

AS THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY of Stonewall approaches, there are numerous visual arts projects illuminating the legacy of early queer liberationists, particularly subsequent generations of out artists who took up the mantle of social and political change.

Art After Stonewall, a sumptuous exhibition of queer æsthetics assembled by New York University’s Grey Art Gallery and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, features artwork by a pantheon of LGBT luminaries, including Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Catherine Opie, Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, Barbara Hammer, Keith Haring, Marlon Riggs, and Andy Warhol.

Alongside paintings, sculpture, film clips, video, music, and historical documents, documentary photography plays a central role in the exhibition. Insightful essays, reminiscences, and interviews highlight forgotten pioneers and contextualize this “next generation of artists politicized by Stonewall.” Straight-identified artists who ventured into queer territory in their art-making are also included: Lynda Bengalis’ nude self-portrait with a two-headed rubber dildo, Nancy Grossman’s black leather fetish masks, and George Segal’s white plaster statues titled Gay Liberation, which were installed in 1980 in Christopher Park opposite the site of the Stonewall Riots.

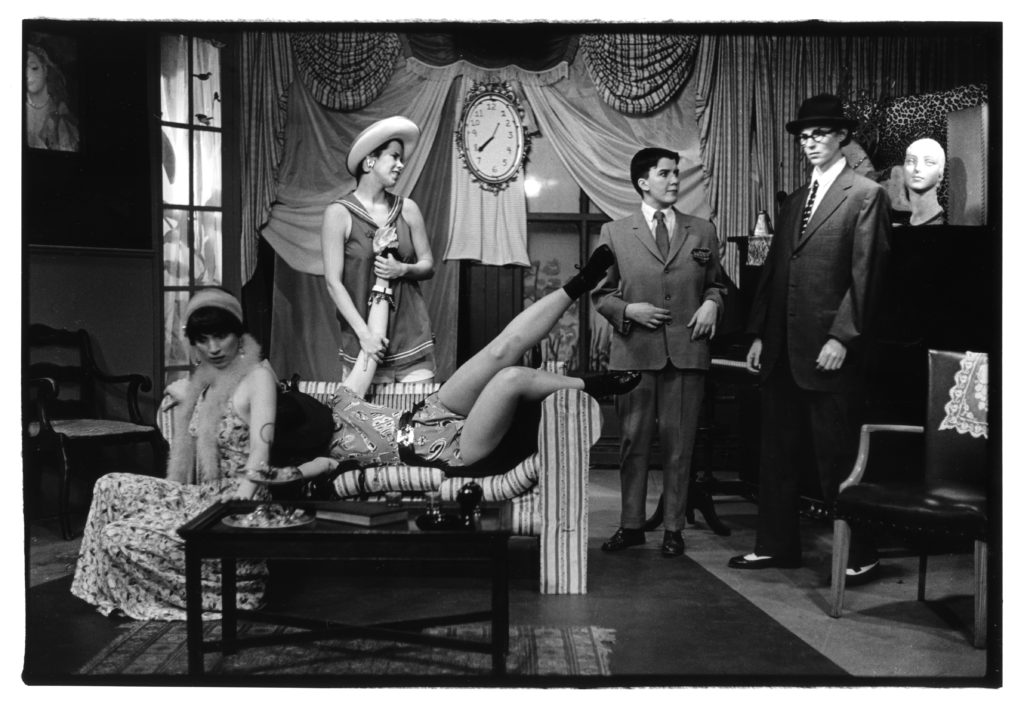

In one section of the catalogue, photographer Dona Ann McAdams writes about New York’s WOW [Women’s One World] Café in the 1980s as a safe space for women, particularly lesbian artists, to perform and develop their craft. A selection of her theatrical images is featured in the exhibition, including documentation of an early work by Tony Award-winning playwright and performer Lisa Kron, a piece titled Paradykes Lost that mischievously played with butch–femme tropes within a “whodunit” murder mystery.

Another project pertinent to Stonewall’s anniversary comes from Matthew Riemer & Leighton Brown, creators of the influential Instagram account @lgbt_history. Their gorgeously illustrated book, We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power, and Pride in the History of Queer Liberation, documents LGBT activism from its roots in late 19th-century Europe to the present day. Meticulous research accompanies indelible images depicting ferocious outrage, glorious celebration, and profound mourning, making this an essential reference for generations to come.

While the Art After Stonewall exhibition features mostly well-known artists, the authors of We Are Everywhere take a more grassroots approach, drawing from the work of seventy photographers and twenty archives—underscoring our diverse and unruly histories: bulldaggers, nellies, leather daddies, trannies, dykes on bikes, punks, and militants, as well as mainstream assimilationists of all ages and races. Buttons, picket signs, newsletters, and other ephemera amplify the narratives of the early organizations beginning in the 1950s, notably the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis on the West Coast and the Homophile organizations on the East Coast—trailblazers to subsequent generations of gay and lesbian liberationists, AIDS activists, and marriage equality advocates.

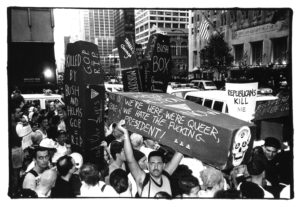

ACT UP at the Waldorf Astoria, New York City, 1990.

Dona Ann McAdams’ photography is featured in both the Art After Stonewall exhibition and the We Are Everywhere book. She too is a child of Stonewall, having chronicled queer æsthetics for over thirty years, adroitly capturing the urgency of early dyke marches, ACT UP actions, and LGBT military members marching in Washington in solidarity against the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy that went into effect in 1994.

McAdams’ agitprop works are also included in a retrospective exhibition that I am curating for Vermont’s Brattleboro Museum and Art Center titled Dona Ann McAdams: Performative Acts, opening on June 22, 2019. Augmenting her photographs of avant-garde performers and pioneers of LGBT liberation, the exhibition includes resplendent black-and-white photographs of people living with schizophrenia, cloistered nuns, and racetrack workers, along with luminous images of horses, oxen, and goats.

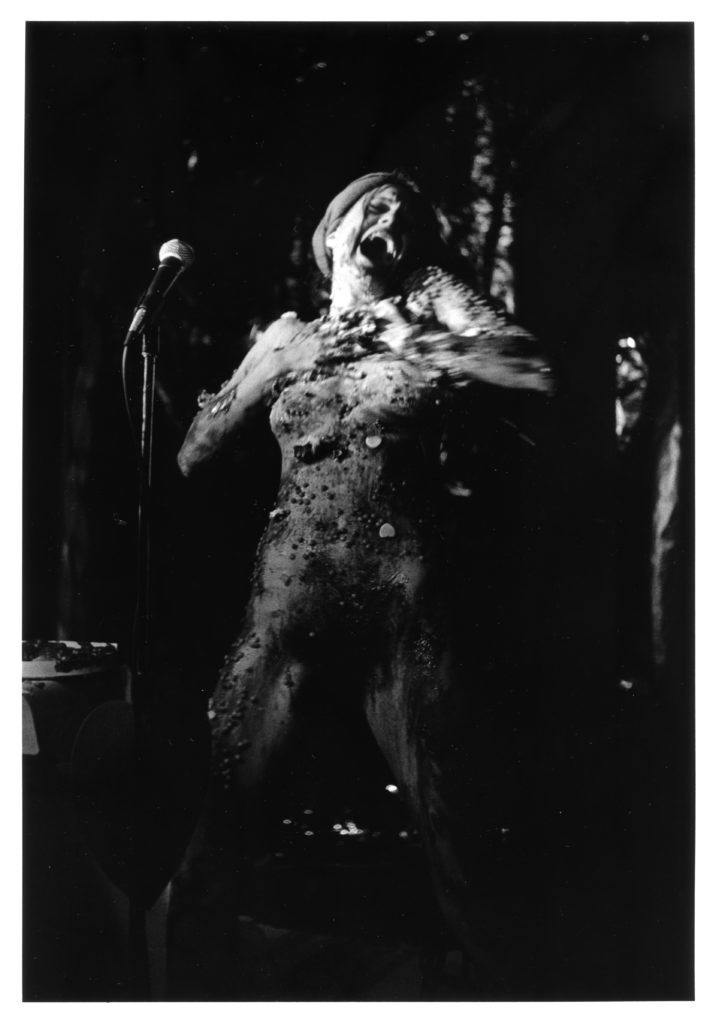

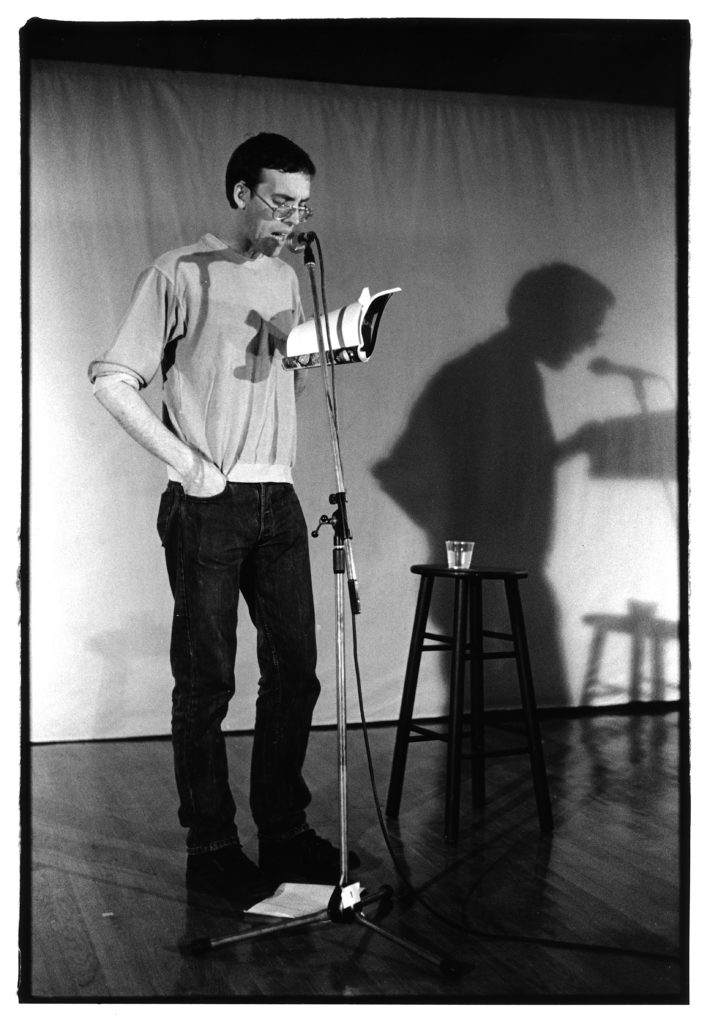

The artist is perhaps best known for her performance images, captured while she was the house photographer for the innovative New York performance space P.S. 122, a position that she held for 23 years. She won an Obie Award for this body of work in 1997 for Distinguished Contribution to Off-Broadway. Her iconic images of the raw splendor of such queer provocateurs as Ron Athey, Ethyl Eichelberger, Tim Miller, Holly Hughes, and Bill T. Jones, who became lightning rods for malicious conservative outrage in the Culture Wars of the 1990s, still resonate today.

McAdams’ iconic print of Karen Finley covered in chocolate performing her feminist AIDS screed We Keep Our Victims Ready, is in both the Art After Stonewall and Performative Acts exhibitions. Finley was one of the artists demonized by Sen. Jesse Helms, who pressured the National Endowment for the Arts to rescind a grant to her in 1990, an action that was later reversed by the Supreme Court. (The so-called “NEA Four” consisted of performance artists Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller.)

Visual artist David Wojnarowicz became another conservative target during this time, when his images were presented out of context and exploited shamelessly as part of a fund-raising campaign by Donald Wildmon and his American Family Association. Wojnarowicz sued this organization for illegal use of his art and eventually won in the Supreme Court, shortly before his death from AIDS at age 37 in 1992. McAdams’ photograph of Wojnarowicz’ fragile fierceness (which is shown on page 31) exemplifies her palpable empathy with her subjects, who are being photographed not as some exotic “other” but instead as participants in the act of portraiture.

Her work is not that of a detached photojournalist but of a fully engaged—and enraged—social activist. She invites the viewer into the particularity of place and into the innate humanity of her subjects. Participatory politics are also a through-line in her æsthetic sensibility. Her documentation of recent history includes anti-Trump protests in Washington and Vermont’s transgender gubernatorial candidate Christine Hallquist marching in a Burlington Pride parade last summer.

McAdams’ photography has been exhibited and collected nationally and internationally, including in museums, galleries, and libraries in New York, Los Angeles, Barcelona, and Paris. In this time of commemorating Stonewall and its legacies, we are reminded how essential McAdams has been and remains in her steadfast commitment to documenting LGBT civil rights struggles—an arts warrior among us.

John R. Killacky, a longtime contributor to these pages, is an elected legislator in the Vermont House of Representatives.