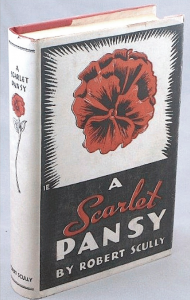

“WHAT The Well of Loneliness did for the man-woman, this most unusual tale does for the woman-man.” This is how an early gay classic was blurbed in advertisements and on the dust jacket flap by Samuel Roth, its first publisher, in 1933. A Scarlet Pansy, by Robert Scully (possibly a pseudonym), is a skillful and mature American novel about forbidden sex, complete with sensational packaging. That a book like A Scarlet Pansy could be displayed and sold openly in 1933 is itself remarkable.

The novel’s omniscient narrator tells the story of protagonist Fay Etrange, presented as a highly sympathetic character for all the surface frivolity of her world. The novel opens with Fay dying in the arms of her lover on a World War I battlefield.

The novel’s omniscient narrator tells the story of protagonist Fay Etrange, presented as a highly sympathetic character for all the surface frivolity of her world. The novel opens with Fay dying in the arms of her lover on a World War I battlefield.