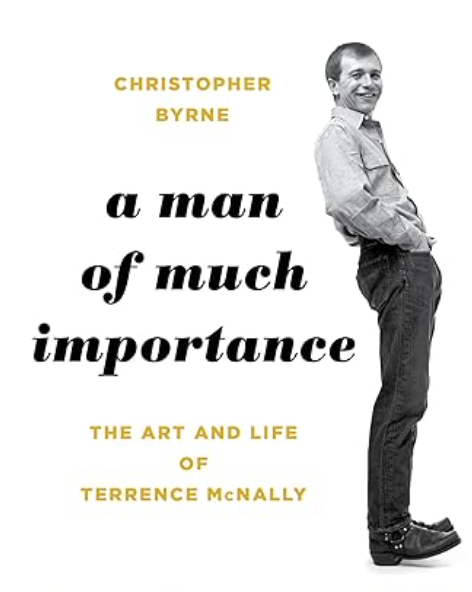

A MAN OF MUCH IMPORTANCE

A MAN OF MUCH IMPORTANCE

The Art and Life of Terrence McNally

by Christopher Byrne

Applause Theatre and Cinema Books 378 pages, $36.95.

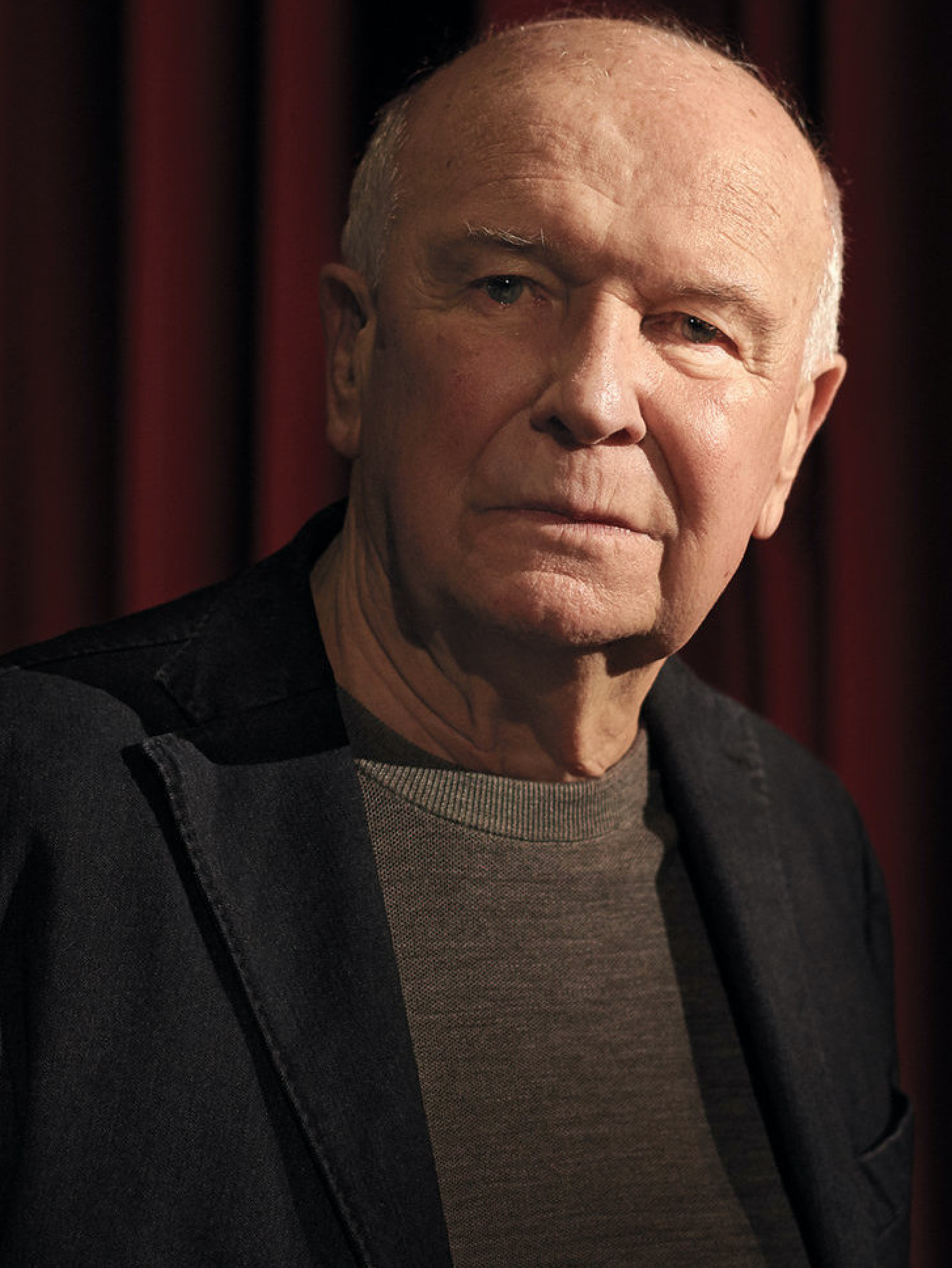

MUCH TO THE IRE of the gay press, Terrence McNally (1938–2020) resisted being called a “gay playwright.” Arguing that the term was “ghettoizing,” he protested on more than one occasion that “I’ll accept the label of ‘gay playwright’ only when Arthur Miller is routinely referred to as a straight playwright.” Yet it is difficult to think of another playwright who has represented gay life as fully as McNally, or who has done more to advance gay rights, including marriage equality and support for people with AIDS.

From the start of his career, McNally dared audiences to reconsider what they thought of homosexuality. Fully four years before Stonewall, his first Broadway play, And Things That Go Bump in the Night (1964), offered the first unabashedly gay character who is neither a neurotic nor a predator. Ten years later, in The Ritz, he not only dared to set a riotous farce in a gay bathhouse with actors dressed only in skimpy towels, but made a running sight gag out of the shocked expressions on the faces of heterosexual interlopers who inadvertently stumble upon the group sexual activities occurring in the steamroom. At the height of the AIDS epidemic, when people were suddenly terrified of physical contact, he depicted one character tenderly sucking the blood from another person’s cut finger in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (1987), dramatizing the simple reality that we die, not physically because we’ve had sex with another person, but emotionally when we’re too frightened to risk life-enhancing intimacy.

McNally’s plays rarely failed to arouse controversy over their gay content, most infamously when, in Corpus Christi (1998), he retold the life of Jesus Christ in terms of a gay teenager’s coming of age in 1950s Texas, turning the marriage feast at Cana into an argument for same-sex marriage, and the healing of a leper into compassion for a person with AIDS. McNally was traduced by religious conservatives in the tabloid press, the theater was forced to install metal detectors to protect theatergoers against bomb threats, and a fatwa (still in effect when McNally died more than twenty years later) was issued against the playwright by the Muslim Defenders of the Prophet Jesus. Homophobic critics ridiculed his celebration of gay men’s love of opera divas in The Lisbon Traviata (1989) and of silver screen goddesses in Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993), and audiences gasped at his use of full-frontal nudity in Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994) to explore the bonds that connect gay men. Two late period plays—Some Men (2007) and Mothers and Sons (2014)—movingly chronicled the changes in gay life from the 1920s to the present day and dramatized the homophobia, both external and internalized, that diminishes gay life.

Christopher Byrne’s biography is welcome on several counts. First, despite the choppy way that it consigns McNally’s plays, operas, and work for television to separate chapters, the book does offer an accurate overview of McNally’s life that’s surprising in some of its details. For example, while McNally had spoken publicly about his parents’ alcoholism and his father’s beating him for his artsy behaviors and sassy comebacks as he grew up in Corpus Christi, Byrne is the first to report that McNally’s mother “interfered” (Byrne’s word) with him during his teenage years, which perhaps explains the sexually troubled relationship between mothers and sons in his plays.

Second, Byrne was able to interview a number of McNally’s collaborators—including actors Nathan Lane and Christine Baranski, director John Tillinger, and Manhattan Theatre Club Artistic Director Lynne Meadow—allowing him to offer valuable insights into how several of McNally’s plays evolved from early rehearsals to opening night performance. I chortled to read that The Lisbon Traviata was originally commissioned by National Public Radio as a radio play, but that the government-supported broadcaster dropped its option because it was uncomfortable with the play’s frank look at contemporary gay life. Likewise, it is illuminating to read the participants’ recollections of the rocky development process of Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991), now widely considered to be one of McNally’s greatest works.

Second, Byrne was able to interview a number of McNally’s collaborators—including actors Nathan Lane and Christine Baranski, director John Tillinger, and Manhattan Theatre Club Artistic Director Lynne Meadow—allowing him to offer valuable insights into how several of McNally’s plays evolved from early rehearsals to opening night performance. I chortled to read that The Lisbon Traviata was originally commissioned by National Public Radio as a radio play, but that the government-supported broadcaster dropped its option because it was uncomfortable with the play’s frank look at contemporary gay life. Likewise, it is illuminating to read the participants’ recollections of the rocky development process of Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991), now widely considered to be one of McNally’s greatest works.

There is, however, much that disappoints in this biography. As Byrne himself says in his preface, he is not attempting to offer a “definitive biography.” McNally once described himself as “a serial monogamist,” and, while Byrne offers a handsome portrait of the playwright’s relationship with his surviving spouse, lawyer and Tony Award-winning producer Tom Kirdahy, he passes much too quickly over McNally’s earlier extended relationships with Edward Albee and Robert Drivas. McNally has spoken or written about each of these relationships, particularly on the influence of Drivas’ AIDS-related death upon his evolution as a playwright, but Byrne doesn’t use these reports to flesh out his narrative.

The narrative is also undermined by the number of key figures whose testimony Byrne did not capture, many of whom died while the book was in progress (notably: actors Marin Mazzie, Charlotte Rae, Doris Roberts, Angela Lansbury, and Marian Seldes; playwright Edward Albee; and McNally’s close friend, Molly Jones). Of greater concern is the fact that the book is undocumented, so one is unable to check, for example, on the source of a misstatement within a quotation. What’s more, much of the writing is syntactically sloppy and badly punctuated.

Finally, I’m troubled by Byrne’s failure to understand the guiding principle of McNally’s life and the humanity of his art. All through his career, McNally was at pains to stress the equal importance of every person in the human community. (“We’re each special. We’re each ordinary. We’re each divine,” Joshua teaches his disciples in Corpus Christi.) Yet riffing on the title of the musical A Man of No Importance (2002), Byrne has titled his biography A Man of Much Importance. McNally had a healthy ego and could resent slights, as anyone who provoked his anger knows. But ultimately he was committed to maintaining the difficult balance between applauding individual accomplishment and celebrating the community of equals.

Raymond-Jean Frontain’s most recent book is Conversations with Terrence McNally.