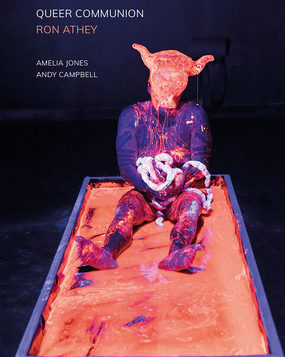

QUEER COMMUNION: Ron Athey

QUEER COMMUNION: Ron Athey

Edited by Amelia Jones and Andy Campbell

Intellect/University of Chicago Press

439 pages, $37

I WAS Curator of Performing Arts at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from 1988 to1996. Artists were creating fierce and politicized bodies of work; some became entangled with the Culture Wars being waged in the media and in the halls of Congress. In 1994, I presented Ron Athey’s Four Scenes in a Harsh Life.

Athey’s life story is a compelling one. Raised by schizophrenic women in a fundamentalist Pentecostal household, he writes: “By the age of nine, I spoke in tongues, danced in the spirit, and was prone to visions and ecstatic catatonic states.” His first artistic forays emerged out of the Los Angeles punk, leather, sex-club, and modern-primitives scenes of the late 1970s and ’80s. A decade of drug addiction followed. In the early ’90s, Athey amalgamated his experiences into shamanistic rituals of extreme corporeality. Drawing upon his evangelical, punk, and BD/SM roots, he describes his æsthetic thus: “Physically, my work manipulates the human body: acts of bloodletting, branding, piercing, cutting, purging, exhaustive dancing, and gender bending are staged.” This vision, while harsh and unrelenting, is ultimately about redemption. Responses to his theatricalized suffering are cathartic and visceral. Experiencing his work, we witness miracles of survival.

The sold-out Walker performance was well received by an audience of about a hundred.

Frank Rich’s “Trail of Lies” in The New York Times called Athey’s performance “valid, if shocking art,” adding that witnesses said “there was no panic, no dripping of blood, and no health hazard that night in Minneapolis.” Despite Rich’s journalistic clarifications, vituperative argument about Athey’s work became a flashpoint in the National Endowment for the Arts’ re-appropriation battles that summer. Senator Jesse Helms called Athey “a cockroach” on the Senate floor. Representative Bob Dornan termed him a “porno jerk,” and Senator Clifford Stearns ranted about how Athey endangered the audience by the “slopping around of AIDS-infected blood.” By the time Rush Limbaugh railed against the performance on late-night cable TV, “Buckets of AIDS-tainted blood were intentionally thrown at the audience” and “the audience ran for their lives.” Facts clearly didn’t matter. Senator Helms introduced an amendment (that went nowhere) prohibiting the NEA from funding art that involved “human mutilation or invasive bodily procedures on human beings dead or alive; or the drawing or letting of blood.”

That summer, Athey joined an elite group of modern-day provocateurs, including Joel-Peter Witkin, Karen Finley, Andres Serrano, Holly Hughes, Tim Miller, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cheryl Dunye, David Wojnarowicz, and Marlon Riggs, who were demonized by indignant, unformed outrage and became flashpoints in the Culture Wars of the ‘90s. But, unlike many of his cultural infidel colleagues, Athey found his performing career in America essentially ended by the controversy. He eventually moved to London and continued to create critically esteemed work in European and South American clubs, theaters, and festivals. Commissions allowed his work to evolve into operatic proportions with large ensembles and exquisitely rendered production values. In 2014, as he returned home to L.A., the Hammer Museum presented his work—the first American museum to present his performance since the Walker twenty years earlier. I was pleased to lead a post-performance dialogue with the artist that sold-out evening.

Historians, scholars, and academics are beginning to write about Athey and his seminal contributions to theater and performance. In 2013, Intellect Press published Pleading in the Blood: The Art and Performances of Ron Athey, a beautifully illustrated catalogue raisonné in which his extensive œuvre is analyzed, comparing him to Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud, and Yukio Mishima. His papers have now been acquired by the Getty Museum, and a new catalogue, Queer Communion: Ron Athey, edited by art historians Amelia Jones and Andy Campbell, draws from these archives and includes his art, ephemera, performance notes, scripts, sketches, and both published and unpublished writings. Set pieces, props, and costumes are augmented by production photographs as well as formal portraits by Cathy Opie and Dona Ann McAdams, among others.

Athey’s writings flesh out his backstories and influences. Scripts and interviews published in such disparate publications as LA Weekly and Honcho illuminate an inchoate childhood at Pentecostal revival meetings, his nascent proto-punk beginnings, and his gay cruising activity in L.A.’s Griffith Park. An op-ed piece by Athey titled “Polemic of Blood” was published in 2015 by the Walker Art Center. Queer Communion also includes short personal essays from friends and collaborators, including Lydia Lunch, Vaginal Davis, Julie Tolentino, Dominic Johnson, and Bruce LaBruce. He is described most succinctly as an artist who wants “to show that there’s beauty and transcendence in much of what’s considered horrific or tragic.”

John R. Killacky, a longtime contributor to this magazine, is serving in his second term as an elected legislator in the Vermont House of Representatives.