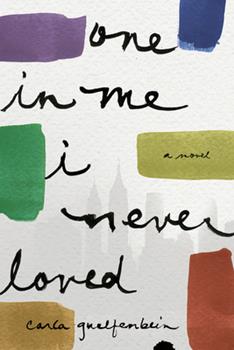

ONE IN ME I NEVER LOVED

ONE IN ME I NEVER LOVED

A Novel

by Carla Guelfenbein

Translated by Neil Davidson

Other Press. 130 pages, $14.99

CARLA Guelfenbein’s eighth novel, skillfully translated by Neil Davidson, centers on the lives and loves of four women living in the neighborhood of Columbia University in the 1940’s and in the present time. One in Me I Never Loved opens with Margarita, a Chilean faculty wife observing her fifty-sixth birthday sitting on a bench at Barnard College waiting for Jorge, her physics professor husband, to appear on the arm of one of his students. “Waiting is a way of disappearing,” Margarita thinks to herself, introducing her exploration of the varieties of disappearance as a key focus of the novel.

But Margarita is not sitting on just any bench; she’s sitting on an actual Barnard Campus structure decorated with sayings by neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, who has given Guelfenbein permission to punctuate the narrative with actual Holzer slogans. This is only one example of the rich artistic underpinning of the novel. Fittingly, a photograph of the actual bench appears on the novel’s last page, suggesting the omnipresence of art in our lives.

Guelfenbein gestures again toward her native country in the second chapter, which transports readers to 1948 and the life of Doris Dana, the historical lover of Chilean Nobel prizewinner Gabriela Mistral. (In another affirmation of art and Guelfenbein’s Chilean heritage, the novel’s epigraph is drawn from a Mistral poem.) The historical Doris Dana had met Mistral at Barnard College two years earlier and had become the older poet’s agent and lover. The Doris in the novel is an aspiring writer herself who has fled to New York to find her own artistic voice and to indulge “the need to lose herself, to fill the room with something other than Gabriela’s voice.” As Jenny Holzer’s expressions punctuate Margarita’s narrative, Mistral’s language enters Doris’ narrative in the form of letters of pain and longing, possibly excerpted from the poet’s actual correspondence and certainly the product of Guelfenbein’s extensive research.

A third character, Juliana, is introduced celebrating her thirteenth birthday in 1946, a day that turns bizarre and initiates the novel’s first mystery. A tangential connection to Mistral is hinted at later in the narrative and points to a second theme of the novel, presented as the theory of physicist Erwin Schrö-dinger that “the fact that particles have interacted once means they keep their connection forever.” The presence of street art is once again asserted in a meeting between Juliana and Margarita 64 years later at the Hungarian Pastry Shop, an Upper West Side landmark with a poster at the entrance reading “Expect a Miracle Every Day.”

A fourth character is Elizabeth, who has deliberately abandoned her wealthy Long Island friends and family and sought anonymity and learning in an apartment near Columbia. Her chapters are rendered in a series of letters written to her friend Kristina in 1946. The theme of disappearance is overt here, and Elizabeth repeatedly instructs Kristina to burn her letters after reading them so that her family won’t find her. It is only in the last few pages of this section that we learn something unexpected about Kristina in a novel that’s full of surprises. For example, we learn that Elizabeth is tangentially connected to Juliana and Doris from a previous section.

A colorful array of secondary figures populates the novel and propels the story. During her sojourn in New York, Doris is having an affair with Aline, a childhood friend and bohemian socialite who is, coincidentally, Elizabeth’s sister. Anne, the security guard at Margarita’s building on 119th Street, dominates the second half of the novel even though she has intentionally disappeared when we meet her in Margarita’s chapters. After her mother Lucy enlists Margarita’s help in discovering Anne’s whereabouts, the novel assumes the pace and urgency of a mystery, heightened by the inclusion of a chapter with Margarita and Lucy that’s written entirely in dialogue.

At another key point in the narrative, the author introduces the elaboration of Schrödinger’s theory by Argentine physicist Juan Maldacena, who postulated that “two particles that have been in contact are not only connected … but are always close.” This principle points to the relationships of all of the figures who appear in this suggestive novel. Certain enigmas are clarified; some secrets are revealed or explored. Others remain mysterious. And the sense of the not yet understood hovers everywhere.

Readers may be propelled through the pages of this slim volume out of a need to solve its many puzzles. The novel’s appeal also lies in its skillful mastery of form, the abundance of its literary and artistic reference points, and the ultimate open-endedness of its conclusions. It is as though Guelfenbein were a street performer twirling several plates in the air at once. And when the novel closes and the plates come down, the audience comes away feeling satisfied yet still curious, awaiting the next project of this very talented, provocative writer.

Anne Charles lives in Montpelier, VT. With her partner and a friend, she co-hosts the cable-access show All Things lgbtq.