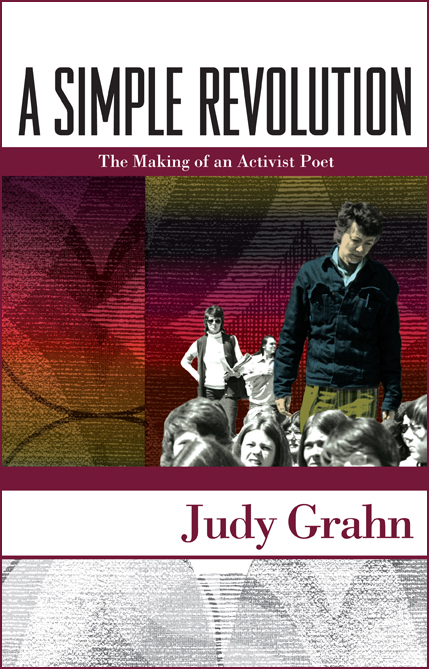

A Simple Revolution: The Making of an Activist Poet

A Simple Revolution: The Making of an Activist Poet

by Judy Grahn

Aunt Lute Books

360 pages, $19.95

JUDY GRAHN was born in Chicago in 1940. This is just about the only ordinary thing that can be said about Grahn, a self-identified working-class lesbian poet who became an uncommonly powerful voice in the women’s and gay liberation movements of the 1970s.

Grahn’s new memoir, A Simple Revolution: The Making of an Activist Poet, traces the provenance of her poems and the path they took from her life experience to the printed page. Writes Grahn, referring to her famous mimeographed, self-published collection of poems (1978): “After the Common Woman poems arrived, the wind holding my life in position suddenly exhaled, and everything changed. Women wanted copies and I could hardly keep enough on hand.”

This exhalation is the “simple revolution” of the title, that of an openly lesbian poet creating a new world with her words, where her words are celebrated, passed from hand to hand, and memorized by heart. In her characteristic blend of humility and confidence, Grahn writes: “I’m sure many women’s movement poets must also have experienced people standing in line to tell them the poetry had literally saved their lives, had given them hope for the first time, had taken them through a hard time, had spurred them to change their lives for the better.”

Grahn tells fascinating stories of her working-class origins, lesbian lovers, brutal hardships in the military, lousy jobs, and activist  breakthroughs. She charts a course through her homes and “all-women’s households” in Chicago, New Mexico, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Oakland. She recounts the tears, anguish, anger, laughs, travels, and sisterhood that went into making her an activist and a poet. As a lesbian poet myself, I was especially delighted to hear about the circumstances surrounding the birth of individual poems, her internal dramas of influence, inspiration, and creation. An important love in Grahn’s life, Wendy, once asked her, “Just why is it that you write? What is it for?” Grahn says these questions still haunt her, and that she has realized that poetry is “more than a ride on the breath-horse of the times. … An activist poet stirs the world to action.”

breakthroughs. She charts a course through her homes and “all-women’s households” in Chicago, New Mexico, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Oakland. She recounts the tears, anguish, anger, laughs, travels, and sisterhood that went into making her an activist and a poet. As a lesbian poet myself, I was especially delighted to hear about the circumstances surrounding the birth of individual poems, her internal dramas of influence, inspiration, and creation. An important love in Grahn’s life, Wendy, once asked her, “Just why is it that you write? What is it for?” Grahn says these questions still haunt her, and that she has realized that poetry is “more than a ride on the breath-horse of the times. … An activist poet stirs the world to action.”

Another important figure in Grahn’s life was her father, who read poetry to her as a child, albeit strictly male poets in the Euro-American literary canon: Carl Sandburg, Robert Service, Robinson Jeffers, Edgar Allen Poe, John Donne, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Grahn reports that Sandburg inspired her with the large and expansive “Chicago” of his poems—one can see his influence in her work—and she seems tenderly appreciative of her father. But certainly Grahn must also have felt a serious lack of poetic foremothers. And then, kaboom! Due in large part to Grahn’s example, there was a huge exhalation of lesbian poets all over America; Grahn says we were all writing poems in the 1970s. Her stories about Pat Parker and Adrienne Rich are thrilling, as are the road-trip tales of giving readings in our freshly created literary world.

In a recent Los Angeles Times interview, Grahn explains: “I tried for many years to have my memoir published on the East Coast without success; I couldn’t find an agent who was willing to handle it. So, once again, you go to the people [Aunt Lute Books] to carry it on.” Shame on the East Coast for once again failing to recognize a great lesbian-feminist poet. Grahn is in full strength in her memoir and uses her apocalyptic poetic insights to recount the epic adventure of creating a world that respects and cherishes women, lesbians, and lesbian poetry.

Mary Meriam’s book of poems is titled Conjuring My Leafy Muse.