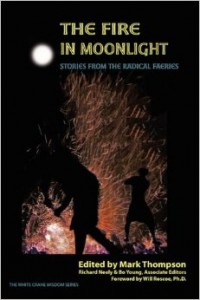

T he Fire in Moonlight: Stories from the Radical Faeries, 1975–2010

he Fire in Moonlight: Stories from the Radical Faeries, 1975–2010

Edited by Mark Thompson

White Crane Books. 309 pages, $25.

IF PROPONENTS of queer theory convened in the seminar room, the Radical Faeries gathered around the bonfire. Both movements—though both resist the label “movement”—arose in the late 1970’s and early 80’s, and both advanced a radical challenge to the assumptions of the ascendant gay assimi- lationism. And both have articulated new gestures of queerness and inspired a younger generation that often takes them for granted.

As retold multiple times in The Fire in Moonlight: Stories from the Radical Faeries, a new anthology edited by Mark Thompson, the Radical Faeries officially began in 1979, with the “spiritual conference for radical fairies” convened by three main organizers: Harry Hay, a founder of the Mattachine Society and grande dame of the gay rights movement; Don Kilhefner, an activist without whom, one learns, nothing would have gotten accomplished; and Mitch Walker, a young would-be shaman. Yet the roots of the Faeries go back further. All three men had grown disillusioned with post-Stonewall gay life, which they saw as increasingly milquetoast politically and vapid culturally, filled with clones, objectification, and discos. These three, along with Murray Edelman, Arthur Evans, Mikel Wilson, Carl Wittman, and others, had already begun to coalesce into workshops, rituals, and even small communities, emphasizing spiritual growth, “conscious” libertine sexuality, distinctive roles for queer people in society, alternative forms of community, and often, though not always, radical politics.