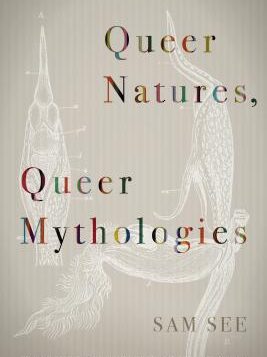

Queer Natures, Queer Mythologies

Queer Natures, Queer Mythologies

by Sam See

Fordham U. Press. 336 pages, $30.

SAM SEE was a professor of English at Yale who died in 2013 at age 34. For those interested in the strange details of his short life, involving his husband, escort services, court orders, and miscellaneous strife, the news media has all those. See’s specialty was queer issues and themes from the classics through the early 20th century. This collection contains previously published and complete but unpublished material, with an introduction and three essays by other writers. It is essentially a Festschrift focused on the main themes of See’s work. The book is long, dense, academic in nature, and thus largely of interest to specialists in the field. If you are comfortable navigating a text featuring “anacoluthon, chiasmus and catachresis,” this book is your natural habitat, deep in the bayous of critical technical English.

Nature is one of its major themes, with a long chapter on rooting ideas of queerness in the works of Charles Darwin. This chapter is frustrating, as it trawls Darwin’s writings for examples of uncertainty and the inherent unpredictability of the natural world, using those as hooks on which to hang a broad speculation that queerness as a cultural fact exists as a consequence or an inevitable parallel of constant variability in nature.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.