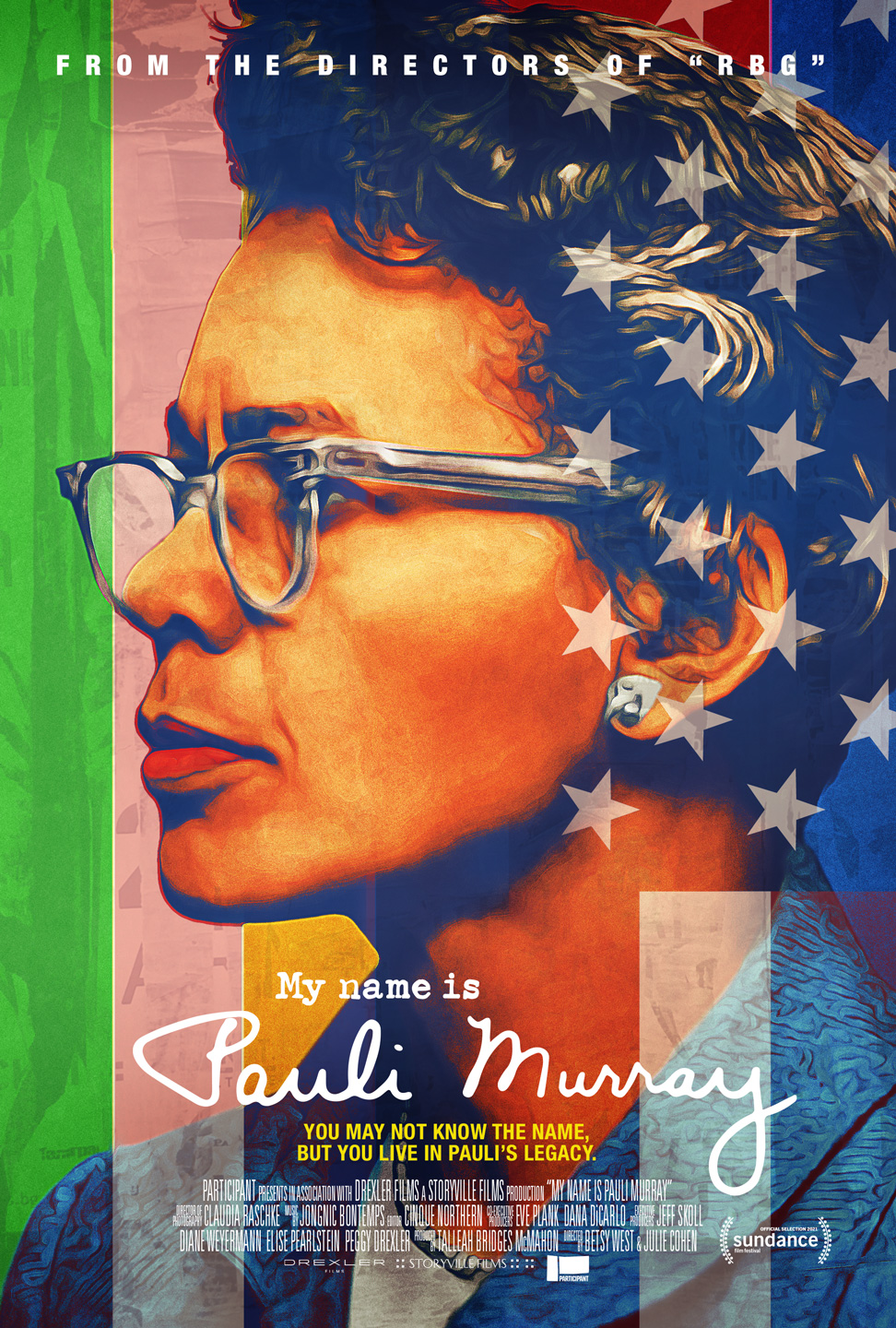

FILMMAKERS Betsy West and Julia Cohen first gained public attention in 2018 with the release of their inspiring documentary RBG. Now they have followed up with My Name Is Pauli Murray, a project of an entirely different order. While Ruth Bader Ginsberg received wide recognition as a Supreme Court Justice, Murray is relatively unknown. So the filmmakers’ task became twofold: to introduce Murray to a general audience and to celebrate her accomplishments. The endeavor was rendered more challenging because of the complexity of their subject’s life. Raised in poverty in the Jim Crow South, Murray struggled against racism and sexism for much of her life. In addition, internal conflict over gender identity and relationships with women called for privacy in a figure who at certain points sought publicity in the service of causes that she espoused. (Note: I use the term “woman” advisedly. A transgender designation was not available at the time, and she was known by female pronouns.)

Anne Charles lives in Montpelier, VT. With her partner and a friend, she co-hosts the cable-access show All Things LGBTQ.