THIS YEAR I’ve reviewed half a dozen of the ten or so films that I saw in June at the Provincetown International Film Festival—not officially an LGBT filmfest, but hey, it’s P’town. And an excellent crop of films it was this year.

Richard Schneider Jr.

This German-Israeli coproduction opens with a seduction. After buying his favorite cookies from Thomas, the “cakemaker” of the title, Oren, an Israeli businessman who frequently travels to Berlin, makes a pass at Thomas, and it works. Although a married man, Oren starts a weekend-a-month fling with Thomas; and the two men are falling in love. They keep in touch by telephone, until Oren stops answering. Eventually Thomas learns that his lover has died in a car crash. Shocked by the news, Thomas closes the bakery and heads to Jerusalem to look for Oren’s widow, Anat, whom he finds running her own café. He asks if she has a job opening; she hires him to wash dishes.

What makes this movie fascinating is the sticky situation that Thomas has gotten himself into in Jerusalem, possibly with the best of intentions. In flashbacks, we learn that while making love to Oren he would ask how Oren made love to his wife, and Thomas would perform these same acts upon his lover. Later, when Thomas is seduced by Anat—against his better judgment and his sexual orientation—he gets through it by imagining that he’s having sex with her husband. Part of the film’s mystique is Thomas’ reticent nature: he is not one to talk about his feelings or motives (and in Jerusalem, of all places!). Indeed the initial decision to go to Jerusalem and find Anat remains a central mystery. Did he go as an angel of mercy, to help a widow in distress? Or was he trying to assuage some sense of guilt he felt over his part in the deception? Or did he harbor some crazy idea that being close to Anat could serve as a surrogate for his lost lover?

Another element in the Cakemaker’s success is the lead actor, Tim Kalkhof, who manages to give this taciturn gay man an impressive emotional complexity through facial expressiveness alone. No matinee idol, Kalkhof might at first seem a surprising choice for the leading role, until you realize that this guy is running on pure acting horsepower.

The New York nightclub sensation lasted for less than three years before being shuttered by the IRS, but there for that one brief, shining moment…. This is the story of Studio 54’s two founders, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, high school friends who dreamed of doing something Big. Both were Jewish kids from Brooklyn; Rubell was gay while Schrager was (and is) straight. True to stereotype, Rubell was the social butterfly who greeted people at the front door, especially the celebrities, catering to their needs for attention or privacy, or for drugs; Schrager was the entrepreneur who worked behind the scenes to keep the operation running.

The film’s structure is that of a classical myth: the first half takes us from the dream of two working-class kids to the pinnacle of success that the 54 reached in 1979, the year when the IRS raided its offices and arrested its two owners for skimming large sums of unreported income. They received a sentence of three years but had their stay reduced to a year by informing on other tax evaders. Rubell died of AIDS in 1989; Schrager, whose testimony provides the narrative backbone of the film, went on to found a hotel empire. Director Matt Tyrnauer sets out to answer the question, What made Studio 54 different; why did it become the place for celebrities and wannabes, who waited in droves outside the front door each night clamoring to be let in? We have our answer by opening night, which was a mob scene: it was the hype.

The epic rise and fall of Studio 54 would come to encapsulate—or anticipate—the far more momentous catastrophe that soon befell the gay community at large. With the arrival of AIDS in 1981, the disco scene and party drugs would become part of the morality play that unavoidably colors the memory of what came before. Apart from that historical superimposition, Studio 54 was a phenomenon that came to symbolize a cultural moment or Zeitgeist, much as Stonewall had a decade earlier: the age of disco, the apotheosis of celebrity culture, dreams of sexual enlightenment and divine decadence for all.

“Wild” is a relative term in this reenactment of a time when a glimpse of stocking was something shocking and people conversed in a formal language full of euphemisms and codes, and in complete sentences. That said, this Emily Dickinson is wild relative to the image you probably have of the dreary recluse who squirreled her poems away in desk drawers or even (as I was taught) in the walls of her house. In this version, with Molly Shannon starring as the Belle of Amherst, Ms. Dickinson actively tries to get her poetry published (it’s largely rejected as too strange); enjoys horsing around with her nephew and two nieces; and doesn’t merely pine for Susan as an object of desire.

In fact, the film is almost as much about Susan as it is about Emily, as Susan is the woman in the middle with a complicated situation on her hands. While terminally in love with Emily, she is married to Emily’s brother Austin—an arrangement that she contrived so as to be close to Emily—with whom she has three children, who figure out early on what their mother and aunt are up to, just as Susan is aware that her husband is having a fling with the maid. Dickinson’s poetry gets a bit of an airing—enough to remind us just how layered in metaphor any feelings or desires are in her verse. A light moment occurs when the characters sing one of her poems to the tune of “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” as can be done with many of her poems. Molly Shannon does a nice job portraying Emily as an affable if eccentric genius whose creativity and rebelliousness were not confined to the written word.

More than any other major playwright, Terrence McNally has zeroed in on that tribe that we know so well, creating gay characters as they might appear in their natural habitats, ranging from the pastoral weekends of Love! Valour! Compassion! to the topsy-turvy world of The Lisbon Traviata, where two opera queens’ obsession with Maria Callas takes over their lives and their relationship in grand operatic style.

The challenge faced by director Jeff Kaufman was to tell in ninety minutes the story of a playwright who has been relentlessly prolific for 55 years, and a man who’s had a fairly complicated personal life. Kaufman starts at the beginning with McNally’s itinerant childhood, his move to New York to attend Columbia, and his affair as a handsome young man with playwright Edward Albee. The rest is a romp through the many artistic phases he went through, with clips from some of his best-known plays—Nathan Lane in Lips Together, Teeth Apart, Zoe Caldwell in Master Class—as well as a manageable number of boyfriends, winding up with his longtime husband, Thomas Kirdahy.

The madcap pace of McNally’s career is reflected in the cavalcade of friends and colleagues who put in their two cents as commentators, mostly extolling McNally’s virtues as a writer and collaborator, including (in approximate order of screen time): Nathan Lane, F. Murray Abraham, Tyne Daly, Angela Lansbury, Chita Rivera, Peter McNally (Terrence’s brother), and many others. The effect of all this is that one leaves the theater with head slightly spinning, but with a new admiration for a playwright who has taken huge risks—Corpus Christi, anyone?—while creating a world in which gay lives really do matter in the larger human comedy.

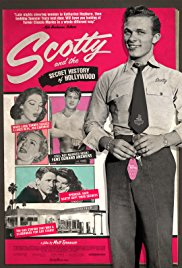

This movie’s title might overstate the case, but it certainly covers a secret history of Hollywood, namely the deeply concealed sex lives of gay and lesbian movie stars in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Call him a matchmaker or a pimp, but Scotty Bowers was the go-to guy for gay trysts who made it possible for many of these heartthrobs (and others) to have a sex life and still maintain the public fiction of heterosexuality. The formula was simple: Scotty ran a Richfield filling station behind which was discreetly parked a large van with two separate compartments, each outfitted with a bed and little else. Scotty would set up the celebrity appointments and supply a suitable male or female love interest. Among his celebrity clients were Rock Hudson, Cary Grant, and Katherine Hepburn—no surprises there, perhaps, but who knew about Charles Laughton? or Spencer Tracy? or Lana Turner?

Interspersed with commentary from living friends and scholars, the director allows Scotty to tell his own story—a sensible strategy, given that questions have been raised about claims in his 2012 memoir Full Service. He may be over ninety, but he still has a steel-trap memory and rattles off names and liaisons as if they happened yesterday. (But, of course, absolute discretion was essential to his trade back then.) Plus, he’s got the goods: the memorabilia, the autographed photographs, even the appointment books. To those who complain that Scotty is “outing” people who are long dead, he points out that their homosexuality was an open secret in Hollywood at the time; only the general public was kept in the dark. In fact, he doesn’t out anyone who hasn’t been outed before; he just tells us a bit more about how they got their kicks when they filled up at Richfield.

Is there a type of person whose early departure from this mortal coil could have been predicted early on? The list of incandescent flames that burned out quickly is quite long—from Byron, Keats, and Shelley to Hendrix, Joplin, and Cobain—and Alexander McQueen clearly belongs to this roster. A suicide at age forty, he produced more work—more lines of dresses, more runway shows, more zany happenings that turned fashion into performance art—in twenty years than other designers produce in a long career, or never produce. As so often in these cases, the manic energy was fueled by chemicals, with cocaine being the drug of choice, though he was no stranger to alcohol.

The forward propulsion of this film nicely conveys the mad ambition that drew McQueen upwards, such that he was hired to be chief designer of Givenchy at the age of 27 (the year was 1996). The drawback of this approach is that we never pause for long to figure out what made him run. We see him scribbling, stitching, dressing models, taking bows, and occasionally talking to the camera, always in cryptic sound bites with nary a complete sentence to be heard. His childlike enthusiasm reminds one of Warhol, as does his general refusal to elaborate on his vision for a given show, or for fashion in general, beyond throwing out adjectives like new, fantastic, or mind-blowing. There’s some suggestion that his fascination with the grotesque went back to childhood abuse, but McQueen himself is not forthcoming on this point. Like Warhol, he seems to have possessed a nonverbal imagination that enabled him to create amazing things without being able to explain what he was doing.