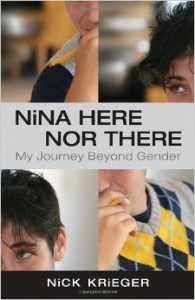

Nina Here Nor There: My Journey Beyond Gender

Nina Here Nor There: My Journey Beyond Gender

by Nick Krieger

Beacon Press. 202 pages, $15

THIS FASCINATING, deeply personal memoir recounts the author’s experience of transitioning from a female to a male identity, and learning through the process that gender is a much more fluid and varied idea than might appear at first glance.

Nick Krieger, originally known as Nina, discovers the transgender community while living in San Francisco. Reaching her thirties, she moves in with a group of younger queers who push the boundaries of gender by having “top” surgery, taking hormones, and changing their names. Some members undergo all of these processes, while others experiment with only one or a combination. In this way, Krieger explores the spectrum of possibilities available; one does not have to simply change from female to male or vice-versa. Through interviewing and speaking with these folks, she learns about her own feelings towards her body and gender.