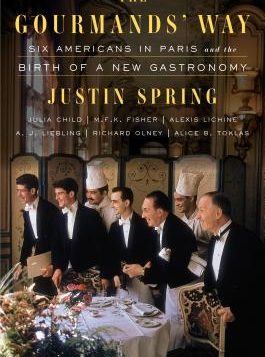

The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and

The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and

the Birth of a New Gastronomy

by Justin Spring

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

448 pages, $30.

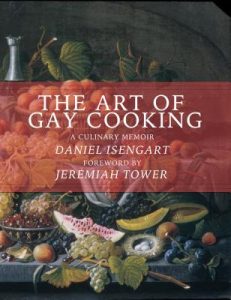

The Art of Gay Cooking: A Culinary Memoir

The Art of Gay Cooking: A Culinary Memoir

by Daniel Isengart

Outpost19. 350 pages, $18.50

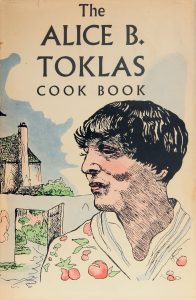

COOKBOOKS by openly lesbian and gay authors have been published steadily over the decades, with Alice B. Toklas leading the charge. Many are fund-raising efforts for gay or lesbian organizations, while others are collections of recipes and reminiscences, such as Cookin’ with Honey: What Literary Lesbians Eat, edited by Amy Scholder (1996), with contributions by Dorothy Allison, Cheryl Clarke, and Jewelle Gomez (among others). And there’s no end of books by LGBT authors that include a selection of recipes, such as the late Lady Chablis’s 1996 Hiding My Candy: The Autobiography of the Grand Empress of Savannah. At the other end of the spectrum are scholarly works such as A Taste of Power: Food and American Identities by Katharina Vester (2015), in which the topic of “Queering the Menu” receives extensive coverage. Daniel Isengart and Justin Spring have made important new additions to this subgenre.

The multi-talented Isengart is a Munich-born, Paris-raised, Manhattan-based performance artist and writer who once made his living as a private chef. His fascination with Alice B. Toklas is apparent from the style that he brings to his gossipy culinary memoir, The Art of Gay Cooking. As in Toklas’ original Cook Book (1954), recipes and memories flow into each other, and, following Toklas, they are written in a style that doesn’t allow for a quick reading of ingredients or instructions. Isengart has an easy if slightly arch writing style, but this is a richly overstuffed book best digested in small portions.

His recipes range from those remembered from his Continental childhood to elegant dishes that he developed while working for wealthy New Yorkers as a private chef. His chapters, like those in Toklas’ Cook Book, are illustrated with black-and-white drawings. Hers were by her friend Sir Francis Rose, the artist initially championed decades earlier by Gertrude Stein. Isengart’s are by his partner, the conceptual artist Filip Noterdaeme. One image shows a young Elvis crooning over a peanut butter sandwich; another shows Noterdaeme and Isengart, shirtless, about to dig into a enormous sundae.

His recipes range from those remembered from his Continental childhood to elegant dishes that he developed while working for wealthy New Yorkers as a private chef. His chapters, like those in Toklas’ Cook Book, are illustrated with black-and-white drawings. Hers were by her friend Sir Francis Rose, the artist initially championed decades earlier by Gertrude Stein. Isengart’s are by his partner, the conceptual artist Filip Noterdaeme. One image shows a young Elvis crooning over a peanut butter sandwich; another shows Noterdaeme and Isengart, shirtless, about to dig into a enormous sundae.

While Isengart doesn’t include any recipes like Toklas’ infamous hashish fudge, contributed by artist Brion Gysin to the chapter titled “Recipes from Friends” (which includes recipes from such luminaries as Virgil Thomson, Natalie Barney, and Carl van Vechten), he does demonstrate the production of a hashish fudge in a 2016 YouTube video. In a marvelous feat of multitasking, Isengart cooks, narrates, and sings “Light my Fire” and “La Vie en Rose” to piano accompaniment. It serves as quite a memorable way to bring to life his opinion that cooking is a “rewarding pastime for musical people.”

Written under a tight deadline, Toklas’ 1958 Aromas and Flavors of Past and Present contains almost no autobiographical material, but it does have a lengthy introduction and comments by the then popular magazine writer Poppy Cannon, who came under extensive criticism for her inept interpretation of Toklas’ style of cooking. Cannon is mentioned disparagingly in Justin Spring’s The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and the Birth of a New Gastronomy. Alice B. Toklas, the bisexual M. F. K. Fisher, and the openly gay Richard Olney (as well as A. J. Liebing, Julia Child, and Alexis Lichine) are the six Americans from the subtitle. Spring devotes more pages to some than to others, and in several cases their personal and professional lives intersected. Isengart states that Richard Olney (1927–1999) should be better known than he is, and it’s a pleasure to find that Spring devotes so much attention to him.

Olney wrote numerous books about food and wine, including some of the first to bring French country cooking to American audiences, but to date no biography has been written. He was the oldest of eight children in a small-town Iowa family, and he began his career as a painter. When a promised Fulbright fellowship to Paris was withdrawn in the early 1950s after Olney’s sexual orientation was discovered—he’d made no secret of it—his socially conservative yet entirely supportive father decided to fund Olney’s fellowship himself, and the latter chose to keep France as his permanent residence. Perhaps the most intellectual of the individuals that Spring profiles, Olney had a particularly close friendship with James Baldwin. Beauford Delaney, the Harlem Renaissance-era painter, was Olney’s housemate for a period of time. Olney’s memoir Reflexions was published posthumously in 1999.

A “performer of her own life,” in Spring’s words, the Southern California-born M. F. K. Fisher (1908-1992)—as she styled herself; she was born Mary Frances Kennedy—lived a tumultuous private life, with passionate lesbian relationships in her early and late years and several heterosexual marriages in between. Praised for her writing style, she turned out a plethora of cookbooks (notably for Time-Life’s Foods of the World, a pioneering series, of which Olney was an editor), memoirs, and works of fiction. Of Alice B. Toklas, who died at the age of 89 in 1967, Spring offers extensive publishing histories of both her Cook Book (including the back story on Brion Gysin’s contribution) and Aromas and Flavors. He also dives deeply into her postwar, post-Gertrude life, which involved the constant struggle to make ends meet and to keep up her many friendships.

In addition to chapter notes and a bibliography, Spring includes a surfeit of footnotes, many of which could have been incorporated as parenthetical asides or omitted entirely. But that’s a minor complaint in an otherwise riveting book.

Martha Stone is the literary editor of this magazine.