TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, artist Ray Johnson (1927–1995) left the Barron’s Cove motel on Long Island, drove 100 feet to the 7-Eleven at the foot of the Sag Harbor–North Haven bridge, parked, walked out on the bridge, and jumped. Two kids heard a splash and saw a bald man, fully clothed, doing a casual backstroke—no cries for help, no struggle, just a slow steady progress out into the bay. His body washed up the next day.

Today it is generally assumed that Johnson’s death was not only intentional, it was also a last choreographed action in a concatenation of collages, performative “nothings,” and labyrinthine art world interactions that together represent the long career of an intentionally low-budget, marginal, and puzzling artist. A 1965 New York Times article called him “New York’s most famous unknown artist.” And not much changed over the years: a 2015 Vanity Fair article referred to him as the greatest artist you’ve never heard of.

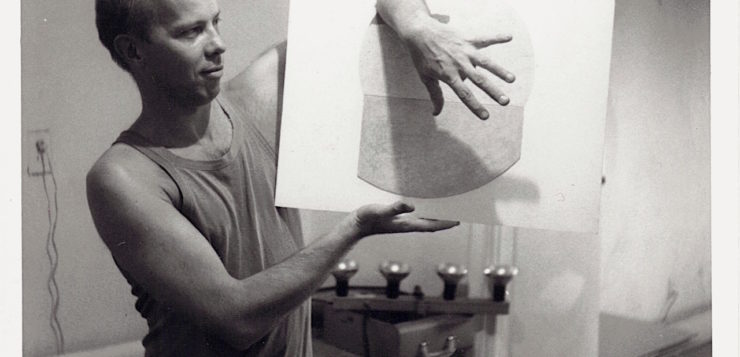

In many ways it seems like he should be positioned as the cynosure of 20th-century American art. His preoccupation with celebrity and the incorporation of commercial and popular imagery into his 1950s collage work predates Andy Warhol, for example, and his performative “nothings” situate him within the developing traditions of the happening and other performance art of the 1960s. His practice of sending art through the mail (which is the art for which he’s best remembered today) traffics in the same theories of art that Robert Rauschenberg and others would later promulgate (art as a shifting product of time, speed, and chance). Under the umbrella of the New York Correspondence School, Johnson mailed an untold number of doctored fragments and unfinished collages, often with the directive to “Add something and send it on.” At times he referred to this action as “Correspondance,” and I can’t help but wonder about the influence of Merce Cunningham, whom Johnson must have known first at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s and later in New York City. Martin Duberman, in his 1972 history of Black Mountain, notes how focused Cunningham was on the centrality of dancing as action rather than as a mechanism for storytelling. A similar impulse can be seen in the playful prompts and emphasis on the spontaneous action (and chance) of Johnson’s mail system. At the same time, Johnson seems to have deliberately claimed his space on the margins of the art world, relocating to Long Island in 1968 and delighting in confounding dealers, collectors, and the general public. Articles and interviews often refer to him as a trickster, puzzler, guru, or court jester, and as someone for whom there was no boundary between art and life. When he died, there was little in his house besides his art (a lot of it, all organized and cataloged) and art-making material. The 2002 documentary How to Draw a Bunny succeeds in illustrating the life-as-art and art-as-puzzle nature of Ray Johnson through the fragmentary perspectives of many who knew him. Indeed, the film, as with much of the writing about him, tends toward a hagiography: Johnson as a sort of Zen master, producing koans of image and text to make us think. Think about what, however, remains debatable. Are they critiques of the art world? Dadaist jokes without meaning? Litter from an exhaustive and complicated brain? Evidence of a gay sensibility? His work is certainly a far cry from some of the more overt political collage and performance work that emerged in the 1980s and ’90s. Johnson, of course, was formed at an earlier time, and one anecdote from Duberman’s history of Black Mountain College is revealing of those times. Consider that just before Johnson arrived there as a student in the mid-1940s, theater teacher Robert Wunsch was fired after getting picked up by police for “unlawful acts” in his roadster with a Marine. So, instead of more overt political or sexual work, Johnson punctuates his art with puns and jokes for a specific audience: what Brad Gooch calls Johnson’s “idiosyncratic, hieroglyphic language.” Looked at in this way, gays might recognize his attraction to movie stars and pop culture and art world references, such as in a newspaper clipping of Andy Warhol, Liza Minnelli, and Paulette Goddard, on which Johnson has copied the phrase “Oh but so lovely” over and over; or an image of Jasper Johns eying a Ben-Day-dots version of James Dean, a Coca-Cola bottle provocatively added at his mouth. Johnson also favored cheeky titles. Some of my favorites include: Diane Varsi’s Mother’s Potato Masher, Buddha Urinating on André Breton, and Untitled (A Star is Born Bunny with Alphabet Buttocks). In the end, Johnson’s death has held as much fascination as his art. Even today, there continues to be a preoccupation with the arithmetic of his death, especially the number thirteen (he died on Friday, January 13, 1995) and numbers adding up to it: he was 67, had checked into room 247, was supposedly last seen alive at 7:15. Yet it remains unknown why he would end his life. As one bewildered article written in 1995 notes, he had just put a new roof on his house. The inexplicability of Johnson’s death, like his life and art, engages us in a loop of tangential and inconclusive contemplation. Even Richard Lippold, the sculptor whom Johnson met at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s and with whom he was lovers for close to thirty years, admits in How to Draw a Rabbit that he really didn’t know Ray Johnson at all. As with a good koan, the answer may be that there is no answer.

Philip Moore is a doctoral candidate at Gratz College in Melrose Park, PA.