THE DEVIANT’S WAR

THE DEVIANT’S WAR

The Homosexual vs. The United States

by Eric Cervini

Farrar, Straus, Giroux

512 pages, $35.

ERIC CERVINI begins his compelling history of Frank Kameny and the Washington, D.C., Mattachine Society with the famous (and infamous) 1960s study of the sexual practices of men in restrooms by sociologist Laud Humphreys. Eventually published in 1970 as Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places, the book was the first to turn public sex into a subject for sociological study, free of the moralisms and legalisms that such activities had been saddled with for decades.

The public restroom holds a particularly important place in the history that Cervini is recounting in The Deviant’s War. In August 1956, a young Frank Kameny—who had just delivered a paper at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting in San Francisco—entered a public restroom and was approached by another man. Police were staking out the restroom, as they often were in the 1950s and 1960s, hiding behind a ventilation grill, spying on the whole encounter. Kameny would be arrested along with his companion. In court, he pled guilty and paid the fine, assuming after a period of probation his arrest would be set aside and the case registered as “dismissed.”

Instead of accepting this outcome, Kameny did something bold: he came out publicly as homosexual and, with the help of the ACLU, took the government to court. It was one of the first legal actions against the government for LGBT workplace discrimination. Cervini expertly maps the legal hurdles that the young Kameny navigated in the following months and years, which ultimately ended at the Supreme Court, where his appeal was finally rejected, ending his hopes of working as an astronomer for the U.S. government. But while his legal fight ended there, his prominence in the case had the effect of thrusting the mild-mannered Kameny into the role of a reluctant political activist, which he remained for the rest of his life.

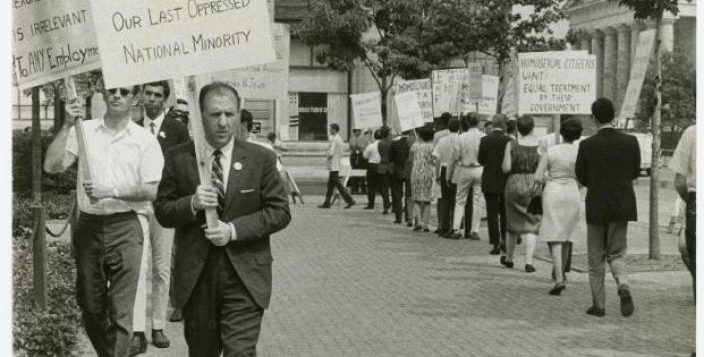

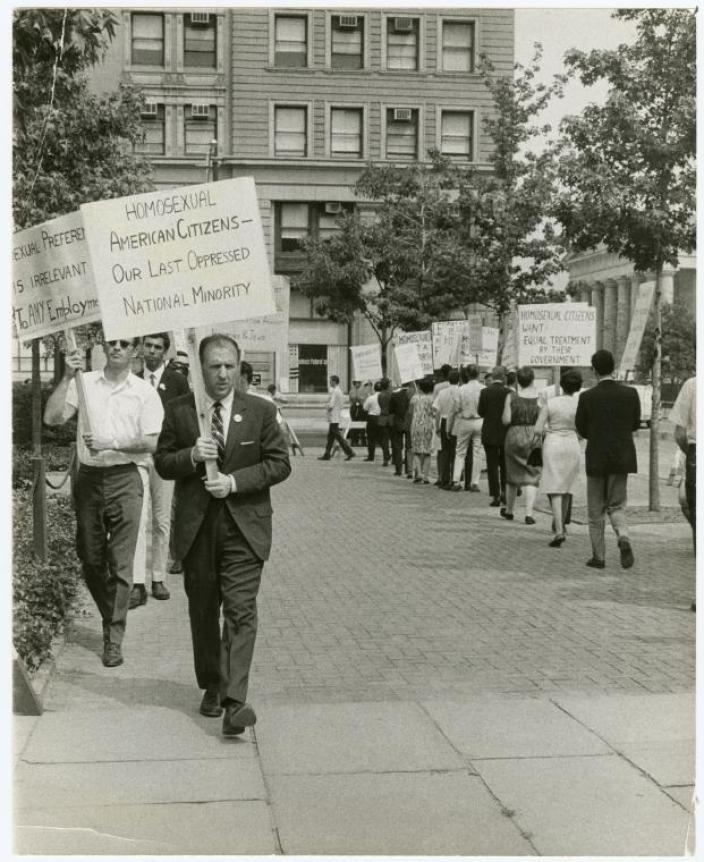

Kameny devised the now familiar “Gay is Good” slogan in the late 1960s, riffing on the slogan “Black is Beautiful” that was being chanted at Civil Rights rallies. As Cervini details, the intersections between the Civil Rights movement and the “Homophile” movement were not lost on Kameny. However, he also shaped a style of gay activism that relied on “respectability” as a political strategy. At their annual Fourth of July protests in Philadelphia, for example, Kameny enforced a strict dress codes for activists. “Picketing is not an occasion for an assertion of personality, individuality, ego, rebellion, generalized non-conformity or anti-conformity,” he wrote to his fellow activists, adding that they all had to be “symbols of acceptability, conventionality, and respectability, as arbitrary as those symbols may be.” Cervini notes that, while Kameny had rejected the need to conform once he took on the U.S. government in his legal battles, he recognized the “trappings of conformity as a political tool,” adding that “it was a matter of image, of strategy.”

The approach to activism would eventually be sidelined in the late 1960s and early ’70s. While the book is anchored to Kameny’s fight and his work with the Mattachine Society in Washington, it is also about the struggles among early activists and arguments between those who, like Kameny, wanted to work within the system through court fights and political lobbying, and those who wanted to take a more radical approach to gay civil rights, connecting this struggle to other oppressed minorities as well as the anti-Vietnam War movement. Groups such as the Gay Liberation Front, founded in 1969, resisted the politics of respectability, advocating a more radical social transformation. But as Cervini points out, this was not simply a conflict between generations; it was a fight over political philosophies. This complicated story, which is detailed through a wide range of sources and evidence, is especially relevant today amid a renewed climate of activism.

The Deviant’s War made it to the New York Times bestseller list in its first month—a rarity for a hefty book of queer history (with 86 pages of endnotes!). This success points to the contemporary relevance of the story, both of Kameny’s fight and of the larger political struggles about social change that we continue to experience. Kameny never became the astronomer he had hoped to be. He struggled throughout his life with finding work and paying the rent. While at times Cervini’s book feels too much like the dissertation it started as, getting mired in the particulars of a timeline, it ultimately tells a powerful story about how Kameny’s fight, and early gay rights activism itself, was deeply shaped by other movements, especially the Civil Rights struggle.

By pure chance, Cervini’s book was published just weeks before the unexpected and historic Supreme Court decision that outlawed discrimination based on sexual orientation for the first time, ruling that the protections in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act apply to LGBT citizens. The Deviant’s War is a stark reminder about the historical echoes of that decision, and the slow march of progress for gay rights in this country—a march that Kameny was so instrumental in sparking six decades ago.

James Polchin is a frequent contributor to these pages and author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall(Counterpoint).