BERLIN CABARETS between the wars had their fair share of homosexual headliners (“homosexual” being the period term). Wilhelm Bendow, affectionately known as Lieschen, portrayed a scatterbrained, giggling “nance” whose naïve questions and double entendres provoked hilarity. Claire Waldoff, a regular at the lesbian clubs with her henna-dyed Prince Valiant hairdo and husky voice, sang of “Kicking the Men Out of Parliament.” They were both wildly popular with all ranks of society.

Despite their unabashed sexual identities, both performers managed to outlive the Nazi regime. Because of a tour to London, Waldoff was forbidden to appear onstage and retired to provincial obscurity. Bendow’s silliness kept him in favor until 1944, when a remark deemed to be politically offensive caused him to spend the last months of the war in a labor camp. He survived to become the beloved “Uncle Willi” on postwar West German television. A more dire fate was reserved for Paul O’Montis. Despite his great celebrity as a stage and recording star, O’Montis was completely erased from the record after his death in a concentration camp. Only now, with the issuance of a biography in German by Ralf Jörg Raber and a CD of fifty of his “greatest hits,” can his career be reconstructed. However, many blanks remain in the record.

O’Montis was born Paul Emanuel Wendel in a small Hungarian town in 1894. German Protestants in a Magyar Catholic community, his family soon moved to Riga. The Slavic culture of the Latvian capital was dominated by a German-speaking population and a Russian administration, so young Wendel grew up a polyglot. At seventeen he wrote the libretto for an operetta that was performed at the German theater there. Despite several successes in that line, he moved to cabaret songs or chansons almost by accident.

When the First World War broke out, the German residents of Riga were regarded as a Fifth Column by the Russian government. Still a minor, Wendel was packed off to a civilian internment camp in Siberia, where he began entertaining to piano accompaniment. As the Tsarist regime unraveled, he escaped in 1917 and wound up at a variety theater in revolutionary Petrograd. Because of his fluency in Russian, no one suspected that he was an enemy “Kraut.” Eventually he managed to get back to Riga, where he starred at the Casino-Theater, offering “intimate songs” packed with innuendo. By this time he had adopted the stage name Paul O. Montis (later O’Montis).

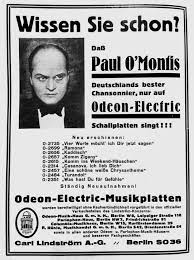

His local celebrity brought him to Munich and Berlin, where he continued to write libretti for operettas. In the Friedrich Hollaender revue Laterna Magica he came to public notice, classified as a Vortragskünstler, which means an artiste who delivers patter with his songs. O’Montis appeared in silent films, published a good deal of pulp fiction, and was a jack of all trades in the performing arts. His enduring fame and fortune, however, came with the new medium of radio. His frequent appearances there led to lucrative recording contracts, beginning in 1927 and resulting in seventy popular “platters.” His first great hits were typically suggestive: “Was hast du für Gefühle, Moritz?” (“What kinds of feelings have you, Moritz?”) and “Die Susi bläst das Saxophon” (“Susie Blows the Saxophone”).

O’Montis’ voice was a light tenor, very much of its time; analogues would be the voices of Noёl Coward and Fred Astaire. Our contemporary Max Raabe (b. 1962) and his band have tried hard to recreate this somewhat effete style. American radio had popularized “Whispering Jack Smith,” so O’Montis was billed as “the whispering chansonnier.” The microphone afforded him a wide variety of effects and enabled him to make points and suggest nuance effortlessly. Critics raved about his “shrewdly balanced technique.” One of them explained: “His technique is to put across the most banal and popular chansons in such a way that they are also fun for more demanding people, because, by standing above them, he wittily satirizes them.”

However, O’Montis was distinguished above all by a racy reliance on what we would call “camp.” Although he had to be careful not to offend against the 1927 “Gesetz zur Bewahrung der Jugend vor Schund- und Schmutzschriften” (Law to Protect Youth against Obscene and Filthy Writing), a measure similar to our present-day legislation against queer and transgender texts, he managed to permeate both his lyrics and his delivery with equivocal messages. The lyric for his earliest recorded hit goes:

Was hast du für Gefühle, Moritz, Moritz, Moritz,

Sind’s kühle oder schwüle, Moritz, Moritz, Moritz,

Du sagst nicht Ja, du sagst nicht Nein,

Du bist so fein, and doch gemein

Du hast eine Herz für viele, Mortiz, Moritz, Moritz

Du bist zu schön, um treu zu sein!

(What kind of feelings have you, Moritz./ Are they cool or warm, Moritz?/ You don’t say Yes, you don’t say No,/ You are so refined and yet so coarse/ You have a heart for many, Moritz/ You are too good-looking to be true!)

The pun on schwül (warm) and schwul (gay) is too obvious to be missed. O’Montis later made a best-selling record camping up a hit from the operetta White Horse Inn (1930): “Was kann der Sigismund dafür, daß er so schön ist?” (“How can Siggy help it if he’s so good-looking?”) (Noel Coward’s “Mad about the Boy” is similarly equivocal. Originally it was written to be sung by a woman in a revue, but once Coward sang it himself in his nightclub act it became a gay anthem.) Via the air waves and the domestic Victrola, O’Montis managed to inject sexual diversity and questionable gender into commercial pop.

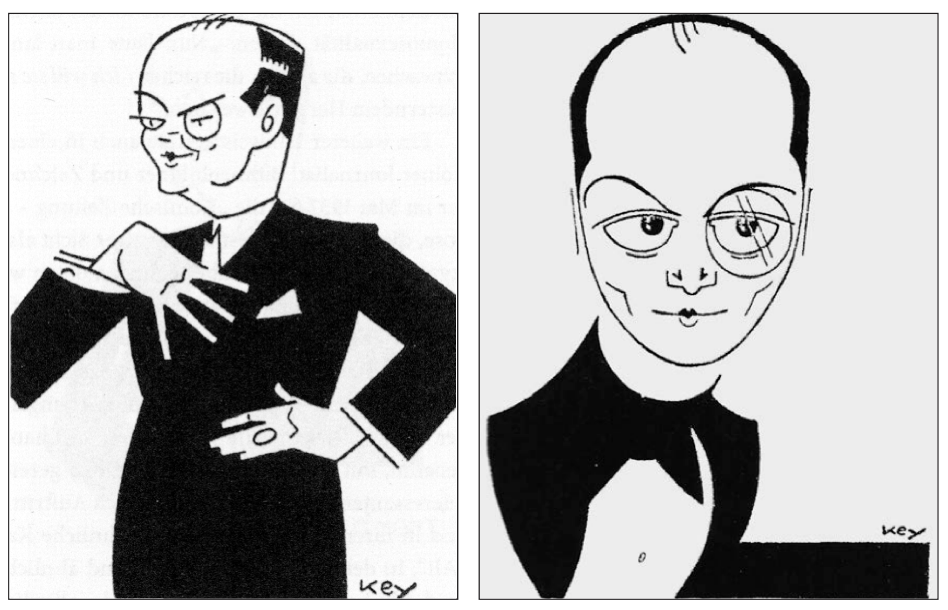

Caricatures and publicity photos made no secret of his effeteness. Impeccably dressed, with a monocle firmly in his left eye and plucked eyebrows, O’Montis was shown in poses that suggested effeminacy (Fig. 2). Baldness aside, he bears a striking resemblance to Peter Lorre’s Joel Cairo in The Maltese Falcon (Fig. 3). O’Montis himself liked to say that he was “beloved of elderly ladies and young gentlemen,” which serves as the title for Raber’s biography.

For all this, O’Montis kept his private life private. Court documents reveal that he probably had liaisons with his piano accompanists Teddy Sinclair (born Theodor Jakob Schmidt) and Franz Hasl. Much of the time he seems to have taken up with working-class youths and hustlers, whose easy availability in Weimar Berlin is attested by Christopher Isherwood’s memoirs. This would ultimately lead to the singer’s downfall.

The notorious Paragraph 175 of the German penal code, which criminalized sex between men, was still in force, but had been something of a dead letter under the Weimar Republic. No sooner had the Nazis come to power in 1933 than they began strictly enforcing it. An attack was launched against homosexual bars and drag clubs. Beyond the disappearance of his favorite haunts, the closing of Jewish firms meant that O’Montis’ recording contracts were not honored.

In December, while touring in Cologne (Fig. 4), he was arrested and imprisoned, accused of “vilely” inducing two youths to “endure unnatural sex acts,” language taken directly from Paragraph 175. One of the alleged victims was reported to be a fifteen-year-old apprentice from a good Cologne family; the other, a year older, “came from another class” and “must be regarded as already corrupted.” O’Montis protested that the boys had approached him and no harm had been done, but the court regarded him as an “uninhibited person” who used “ingenious skill” in passing the teenagers on to “like-minded people.” O’Montis’ private secretary was held as an accessory and a search of the singer’s quarters turned up hundreds of letters from youths throughout Germany.

It was perhaps coincidental that O’Montis’ first encounter with the police came after the Nazi takeover, but the charges also included “making remarks insulting to members of the government and the national party,” calling the Reich ministers Ernst Röhm and Rudolf Hess gay, as well as dissuading the older boy from joining the naval branch of the Hitler Youth. (These were crimes that fell under the purview of the Gestapo.) O’Montis made a statement that he had never belonged to leftist parties and only repeated what he had heard.

The political charges were more serious than the sexual ones. Male prostitution and homosexual activities with minors were not specifically made illegal until 1935, and it was clear that the older boy was a hustler. After a trial in March 1934, O’Montis was sentenced to one year and nine months’ imprisonment and three years’ loss of civil rights, an exceptionally harsh sentence. The usual penalty for infringing Paragraph 175 was a fine or three months in jail.

This ended O’Montis’ career in Germany. On his release, he continued to attract enthusiastic audiences throughout countries with a sizable German-speaking populace: Switzerland (until he was expelled as an “undesirable alien”), Austria, where he was advertised as the “German Maurice Chevalier,” the Netherlands, and Czechoslovakia. Everywhere he was acclaimed by press and public alike and was very well paid. He ventured farther afield to other polyglot nations—Poland and then Yugoslavia, where the reviews were equally glowing.

In Zagreb, however, O’Montis again fell afoul of the police, who recorded that he worked in the Pik-Bar, where “many problematic types known as homosexual” hung out and the pianist was Jewish (he was actually Catholic). His criminal record was known to the Croatian authorities, who noted the homosexual contingent in his audiences and labeled him as “a typical example of a homosexual whom you can spot at first sight,” offering swishy clichés from the stage and flirting with his accompanist. He was deported and in June 1938 returned to Prague.

That September, in the fast-food restaurant the Koruna Automat, he met Josef Roška, an eighteen-year-old with blue eyes and bad teeth, a juvenile delinquent who had twice served time for theft. According to Roška’s subsequent testimony, O’Montis became his “sugar daddy” and they had “perverted intercourse” in his apartment. Aware of his imminent arrest, O’Montis had nowhere to run. This time the sentence was three months’ hard labor and loss of civil rights, but in February 1939 the President of the Republic offered a general amnesty. It was Eduard Beneš’ last act in office before he escaped to London. O’Montis had barely returned to the stage when the troops of the Wehrmacht marched in. Czechoslovakia was now subsumed by the Third Reich.

From this point on, the singer’s decline and fall were rapid. O’Montis was arrested a few months after the occupation and sent directly to prison for the crime of being “a homosexual.” After eleven months’ internment in Prague, in May 1940 he was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where his death and that of his fellow prisoners was assured. “Homosexuals” were segregated from the other inmates: of the 700 there from November 1939 to June 1943, 600 were murdered between April 1940 and April 1943. The few survivors called it “hell on earth” (Fig. 5).

O’Montis, once again Paul Wendel, now wore the pink triangle and was kept in isolation behind barbed wire. He and his fellow prisoners were given no work but had to kneel, arms behind their necks, bare-headed in the rain, or in warm weather made to roll across a hundred-meter-long gravel path. It was customary in these barracks for the “block elders” (often political prisoners who hated “queers”) to implement “suicides” when so ordered. The victim was commanded to go to a bedpost or a latrine and hang himself. In all likelihood, this is how O’Montis died on July 17, 1940, at the age of 46.

Although in the course of his career O’Montis had been one of the brightest stars in the German entertainment world, his squalid demise and his sexual orientation made him a non-person after the war. (Paragraph 175 remained on the books in the German Federal Republic until reunification in 1994.) When I was in West Berlin in the 1970s researching German cabaret culture, I never came across his name. O’Montis was absent from all the publications, exhibitions, and recordings, both West German and East, devoted to this subject. It is noteworthy that the publication of Raber’s biography has been supported by the Bundestiftung Magnus Hirschfeld, an institution founded by the German Ministry of Justice and dedicated to the advancement of queer studies. Such efforts should eventually make invalid the term “hidden from history.”

Laurence Senelick is the editor and translator ofCabaret Performance: Europe 1890–1940.