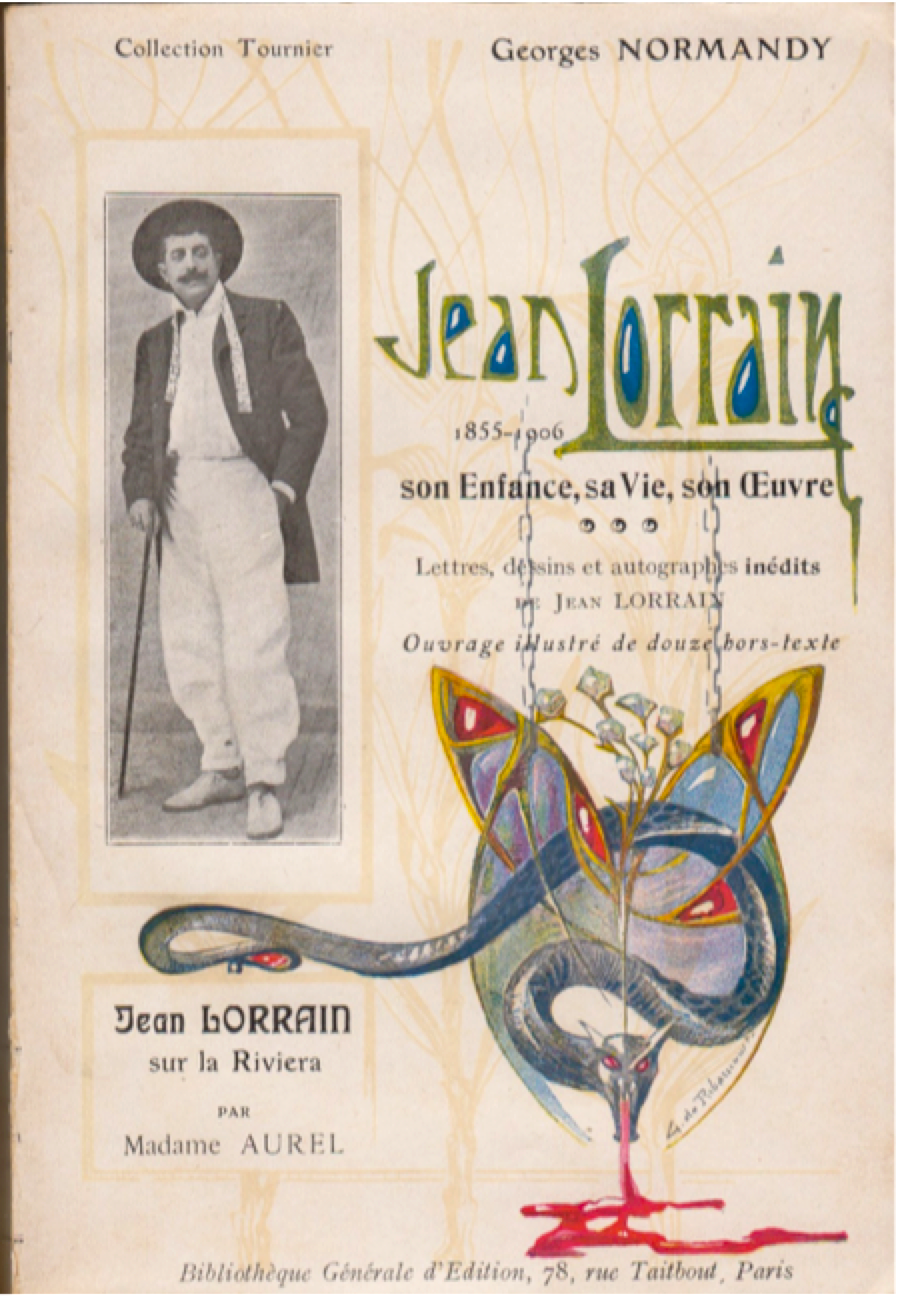

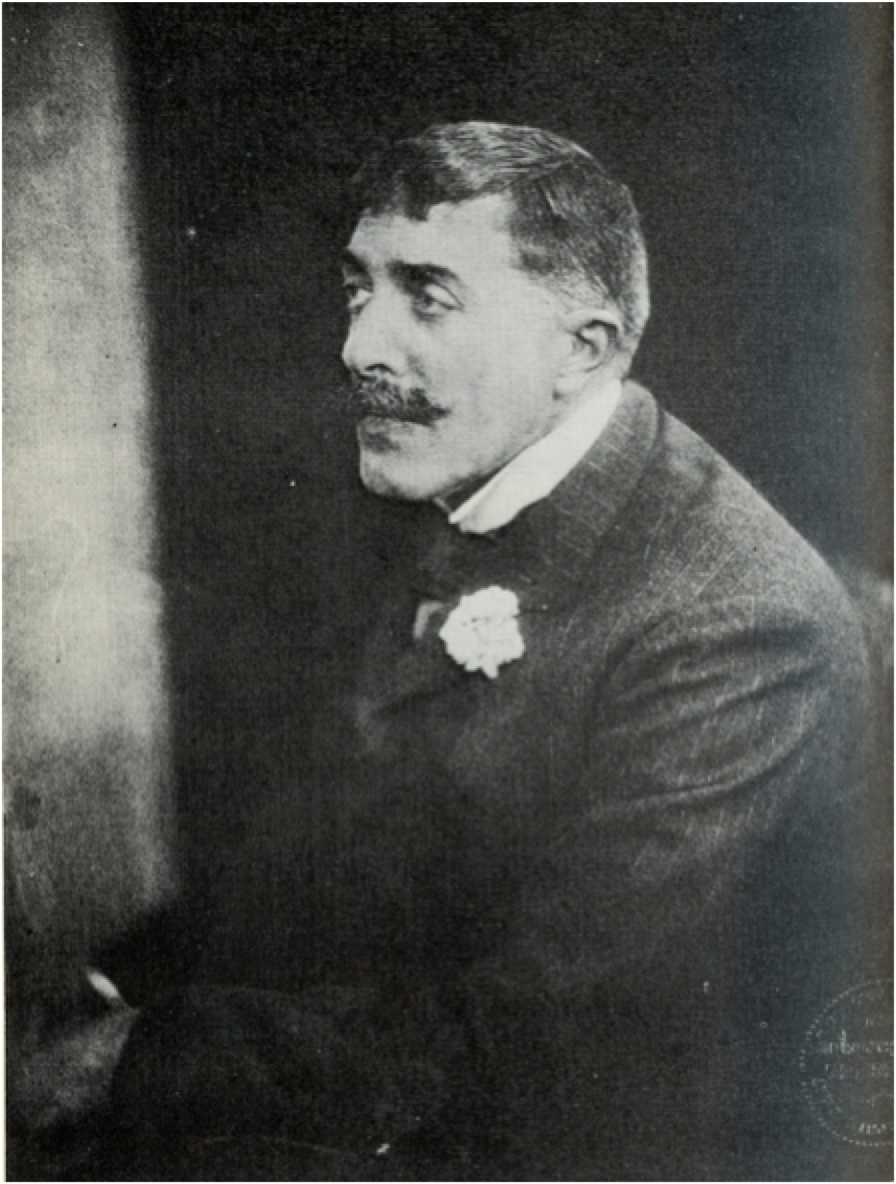

OF ALL THE DECADENTS, dandies, and deviants who enlivened the fin de siècle in France, none was more outrageous than Jean Lorrain (1855–1906). He serves as an early example of the homosexual celebrity as social and artistic arbiter, a role later played to the hilt by Andy Warhol and Truman Capote. His aphorism “What is a vice? A taste one does not share” belongs in every dictionary of quotations. That it doesn’t may be testimony to the sulfurous reputation that lingered long after his disappearance from the scene (Figure 1).

Paul Alexandre Martin Duval, son of a wealthy Normandy ship owner, arrived in Paris in 1881 and set out to make that reputation. When he first began publishing his work, his father insisted that he use a pseudonym, and his doting mother found “Jean Lorrain” in a local directory. His earliest collection of poems, Le sang des dieux (Blood of the Gods, 1882), daringly featured the ephebes of classical mythology: Ganymede, Antinous, “Hylas, his arms polished by Hercules’ kisses,” and the Roman mime Bathyllus scorching sailors in low dives with his come-hither glances and provocative dances. The book met with modest sales but major publicity.

With their emphasis on succulent adolescents, the poems fail to reflect Lorrain’s own weakness for what he called Fleurs de boue (Flowers of Mud, an allusion to Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil), “those gentlemen of the ring, a tiger pelt/ About their loins, bare chests, their own hides fine and clear” (Modernités, 1885). “I am very fond of hooligans, fairground wrestlers, butcher boys and assorted pimps, both plain and fancy,” he boasted. In a fashionable restaurant he declaimed to the astonished diners: “Last night I lay between two stevedores/ Who emptied me of all my passion.” Sex with thugs and ruffians is a recurring theme in his stories. In Sonyeuse (1891), a woman prefers to couple with the basest criminals in the hope of some day attending their executions (Figure 2).

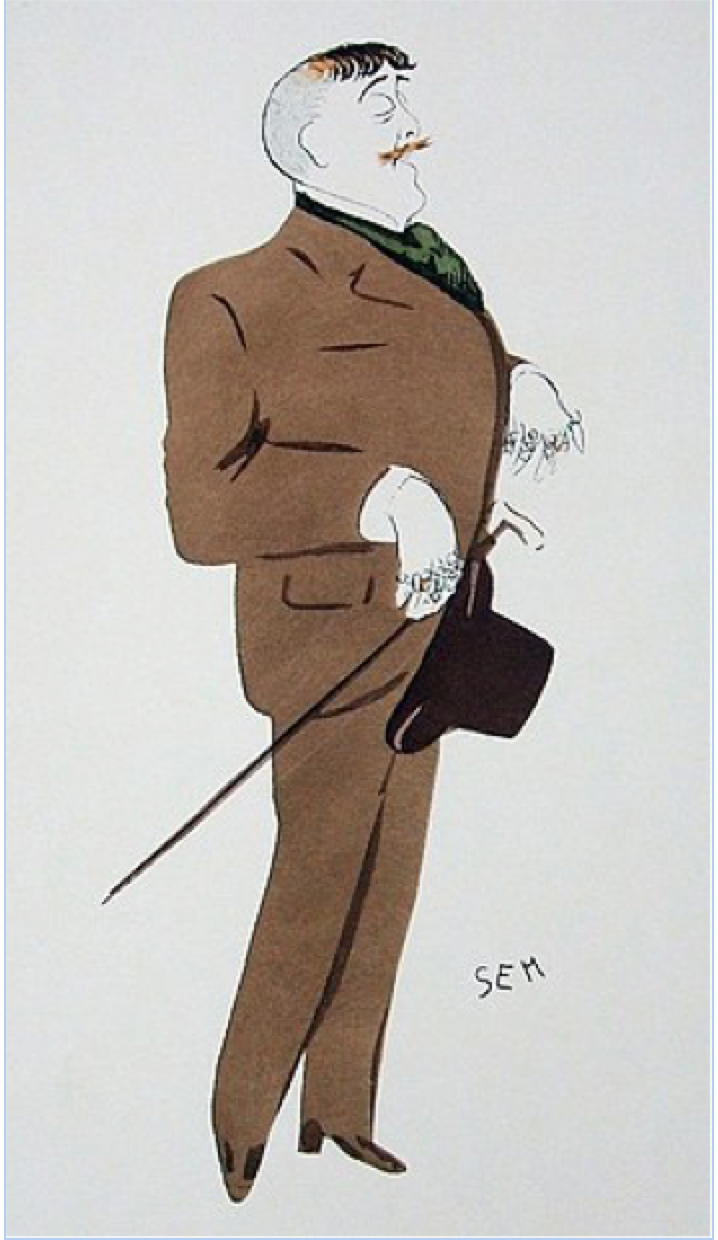

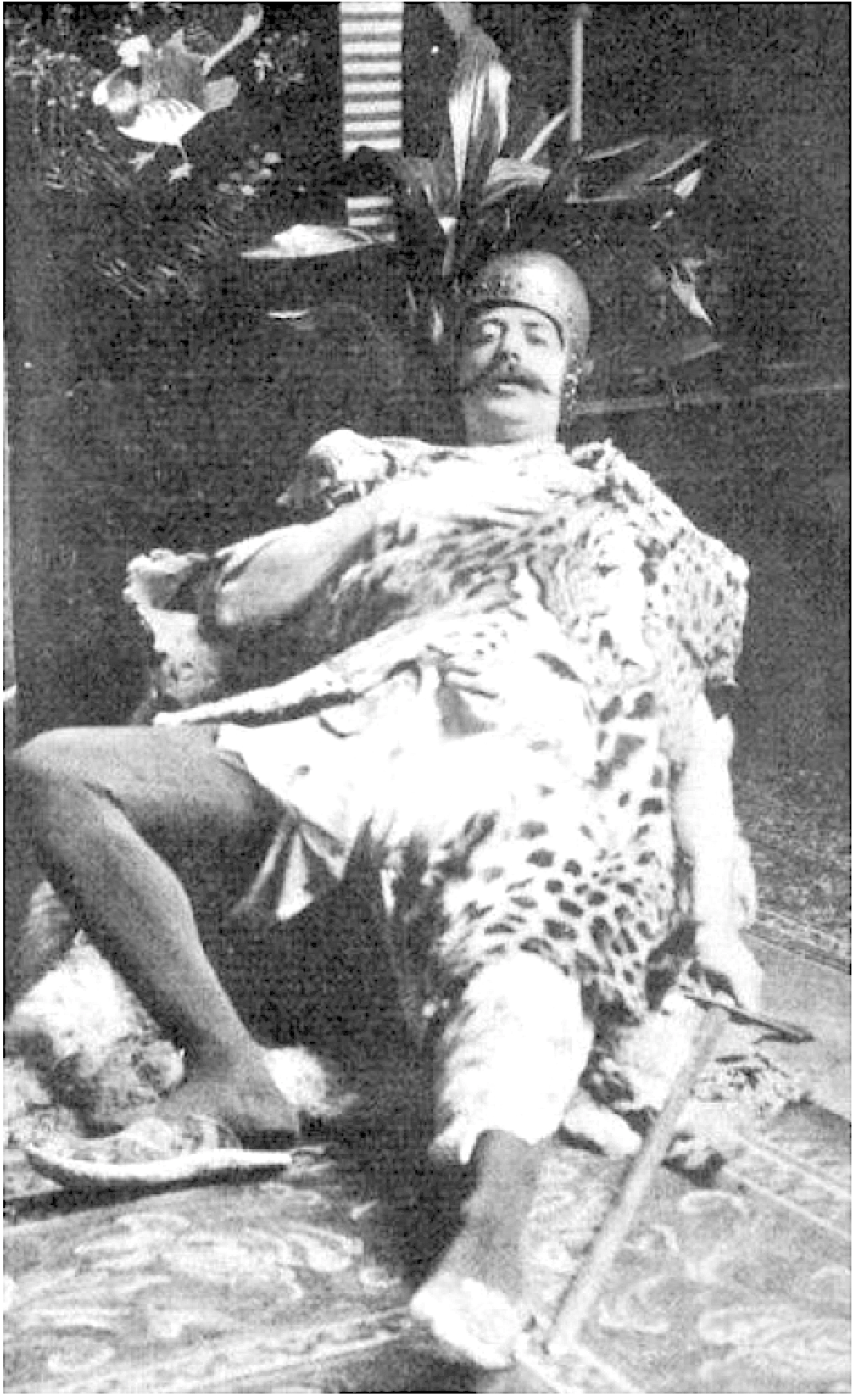

Of strapping physique himself, with the blond moustache of a Viking and a deep bass voice, Lorrain painted his face, dyed his hair garish colors, rimmed his heavy-lidded, bulging eyes with kohl, and adorned his fluttering hands with ornate rings. He attended artists’ balls in outrageous costumes, often escorted by a prize-fighter in tights. “As unctuous as a frosted pastry,” Lorrain became known, in the words of Philippe Jullian, as “the Petronius of the decadence … the best observer of a milieu of which he was also the worst ornament” (Figure 3).

Lorrain haunted galleries and theaters for material to write about, puffing a painter or scorning a star in sensational articles signed with pseudonyms from “Mimosa” to “Stendhaletta.” He soon won infamy as a journalist whose columns were savored for their colorful reportage, innuendo-saturated gossip, and character assassination. They would flay his best friends and apologize profusely afterwards. Nor had he any compunction about mocking others’ sexual penchants, calling Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen “a petty suburban Nero” whose taste for Black Masses and altar boys “is better suited to the pink mass (Vaseline and essence of Guerlain).”

In Le Figaro, in 1896, Lorrain venomously characterized the budding Marcel Proust as one of those “pretty little young men in society down with a bad case of literature.” Proust’s Pleasures and Days is described as a blend of “elegiac flabbiness, elegant and subtle little nothings, pointless tenderness, inane flirtations in a precious and pretentious style.” This was the chamber pot calling the slop bucket smelly. It led to a harmless duel, after which the two ignored one another thoroughly (Figure 4). There is, however, more than a hint of Lorrain in Proust’s Baron de Charlus.

As a writer of fiction, Lorrain spanned the fin de siècle spectrum, from Zola’s squalid naturalism to Maeterlinck’s otherworldly fantasies, but with no sense of proportion or taste. His works are a compendium of the faddish tropes of the period: Florence and Venice; Medusa and Ophelia (“the charm of a virgin and a perverse boy,” Sur un portrait de Botticelli); gems and poppies (“a breast-plate studded with amethyst grips his torso and he wears a huge crown of enormous purplish poppies,” in Coins de Byzance [Byzantine Corners], 1902); melancholy lilies and irises “which revealed to me my infamous and chaste dishonor,” in La forêt bleue [The Blue Forest], 1883); barbarians and Byzantium (“Yes, let them come, let them burn all that is here; let them empty my coffers, let them crush my pearls, let them crucify the steward, let them rape my mother,” in Coins de Byzance); the decorative and esoteric paintings of Gustave Moreau, Jan Toorop, and James Ensor; the actress Sarah Bernhardt, for whom he wrote unproduced plays; the music-hall singer Yvette Guilbert, for whom he composed scabrous ditties; Wagnerian opera and Arthurian legend; grimacing masks and necrophiliac orgies; erotic delirium and odors “of sex, of cosmetics, of sweat.” All this is described in a lapidary style, an indigestible mixture of recondite vocabulary and the latest slang (Figure 5).

Lorrain’s fiction is misogynistic, ruled by women whose morbid and perverse psychology is expressed in furnishings, wardrobes, and scents. Madame Litvinoff in Très Russe (Very Russian, 1886), with the “unsettling smile of the Mona Lisa,” dominates effeminate men, “gentle as a child,” and practices chastity as an erotic refinement. Another of Lorrain’s heroines concentrates on making half-naked acrobats fall from their trapezes and tightropes. The anemic virgin in Âmes d’automne (Autumnal Souls, 1898) wants to warm her chilled extremities inside (literally) the bosom of a stable-boy. Depravity is commonplace in courtesans like the “pianist” whose virtuosic fingers can rouse enfeebled dotards or the twelve-year-old “graveyard hooker” who plays schoolgirl for elderly pedophiles.

Lorrain’s overheated imagination revels in extremes. In Monsieur de Bougrelon (1897), a starving dandy recounts stories of grotesque passion. There is the Mexican dancer, raped fifteen times, who has fifteen rubies embedded in her flesh. Les Norontsoff (1902) tells of a fabulously wealthy Russian prince who, among other extravagances, serves his guests three naked tattooed men on a platter and eventually commits suicide to consummate the desires of his delirious fantasies. Another hypersensitive neurotic, the title character in Monsieur de Phocas (1910), a combination of Dorian Gray and Mr. Hyde, is obsessed with a statue of Antinous and goes to his death seeking a wonderful shade of green once glimpsed in the eyes of the goddess of lust.

A morphine and ether addict, perpetually in failing health, Lorrain excelled at portraying physical decrepitude and superannuated desire. For him, love consists of the intimate contact of two solitary and incompatible beings. It can be expressed only in excess, leading to madness or violence. Characters who long for beauty tend to be repellent lunatics or venal perverts. The dominant mood, a sort of mournful and sadistic sensuality, may be derivative (think Algernon Charles Swinburne, Joris-Karl Huysmans, or Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly), but the overwrought style is all his own.

Although Lorrain was infatuated with the stage, his own plays had scant success. The best attended was his version of Prometheus, performed in 1900 at an open-air amphitheater in Orange and drowned out by a thunderstorm. The flamboyant actor Édouard De Max, Lorrain’s histrionic counterpart, played it in the nude, and the hairdresser who had depilated his body placed the cuttings for sale in his shop window with the sign: “Tuffts [sic: poiles] from the great tragedian De Max” (Figure 6).

Caricaturists had a field day with Lorrain’s pigeon-breasted posing, particularly his desire to be elected to the Académie, an institution he attacked in his columns. Lorrain was pilloried in Carle Armory’s comedy Le monsieur aux chrysanthémes (1908; the title parodies La dame aux camélias). Its camp antihero is a sought-after celebrity journalist who revels in destroying reputations and thwarting heterosexual love affairs. The subject was considered so daring that no actor of repute would take the part.

Note that Armory’s play appeared only after Lorrain had vanished from the scene. Much as he had relished notoriety, he would have riposted savagely to such a frontal attack. Near death, impelled partly by patriotism, partly by a sense of waning fashion, Lorrain overturned the idols of his youth in his unfinished novel Pelléastres (Fans of Pelléas, 1910), savaging æsthetes along with the German Wagner and the Belgian Maeterlinck. Fed up with Paris, he settled in Nice with his one true love, his ever-faithful mother. There he died at the age of fifty, succumbing not to the embraces of a circus roustabout but to an enema that perforated a colon already ravaged by tuberculosis, syphilis, and drug abuse (Figure 7).

Detested by most of his contemporaries and undervalued by his immediate posterity, Lorrain’s amalgam of lowlife culture and preciosity, of exhibitionist journalism and artistic aspirations, has come to be seen as forerunners of Jean Cocteau and Jean Genet. His musky writing may be an acquired taste, but, then, so is caviar.

Laurence Senelick is author of Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture (2017) and the editor-translator of Lovesick: Modernist Plays of Same-Sex Love, 1894–1925 (1999).

Discussion1 Comment

An excellent article introducing us to the great Lorrain.

At the risk of terrible self-promotion Side Real Press in the UK has issued a deluxe limited edition (300 copies) of ‘Monsieur de Bougrelon’ with decadent illustration by the equally wonderful artist and designer Etienne Drian (1885-1961) which originally appeared in a 1927 French-language edition of the book.