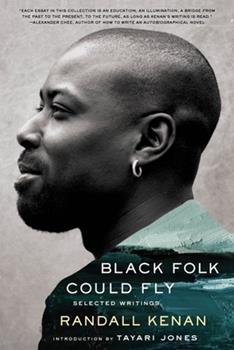

IN AN ESSAY centering on legendary photographer Gordon Parks titled “There’s a Hellhound on Your Trail,” the late Randall Kenan suggests: “The scary truth about fiction and nonfiction is that when it comes to writing, to capturing—the difference is that there is no difference.” This assertion is often felicitously borne out by this posthumous collection of 21 of Kenan’s prose pieces written during his relatively short lifespan.

As Tayari Jones explains in her appreciative introduction, the title of the collection derives from the African-American folktale depicting Africans who flew back to Africa after the slave ships arrived in the U.S. Jones rightly points to the ending of the book’s first selection, “A Change is Gonna Come,” where Kenan explicitly evokes the myth and metaphor as he urges his godson to “Remember that [story]when you think you are stuck in the mud.”

Fans of Kenan’s fiction may well recall the title of his last story collection, If I Had Two Wings, or his dazzling debut novel, A Visitation of Spirits, to recognize the writer’s ongoing preoccupation with folkloric supernaturalism and the otherworldly. In fact, “Ghost Dog or How I Wrote My First Novel,” one of the most appealing pieces in Black Folk Could Fly, traces the tales he heard in childhood of an apparitional white canine who performed various benevolent acts and then disappeared. After multiple engaging detours covering Kenan’s intellectual awakening, including his discovery of such influential figures as Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, and Zora Neale Hurston, the writer circles back to the image of the “ghost dog,” which seems to symbolize his own literary project—which, alas, he did not get to complete due to his premature death at age 57.

Kenan’s childhood in North Carolina is the focus of the first part of the collection, titled “Comfort Me.” Here he reminisces about members of his father’s family who raised him after his birth in Brooklyn as “a love child.” He introduces readers to the great aunt who began taking care of him when he was three and whom he called mother. Friends and neighbors appear as well, inhabitants of the rural village of Chinquapin where “Community was an experienced thing, not simply an idea.” In this section, he recalls chasing a rooster and awakening a rattlesnake, being struck by lightning, discovering sex by seeing two hogs mating, and catching his first glimpse of homosexuality in the 1976 Max Beer film Ode to Billie Joe. These accounts are often rendered in Kenan’s lyrical prose incorporating Whitmanesque list-making that accelerates the narrative and fosters a poetic sense of place.

The impact of the writer’s early years is echoed throughout the last two parts of Black Folk Could Fly. The lens is broadened to include perspectives from the writer’s stint working in a publishing firm in New York and his travels around the U.S. in search of what it means to be Black. Biographical information appears, including an account of a prison visit to his biological father and a snapshot of his problematical relationship with his birth mother. And social commentary inevitably occurs. Kenan observes upon a return visit to his hometown, for example, that “Chinquapin was becoming more like the rest of America. It was being absorbed by the vast cultural soup of consumeristic we-think.” Miscellaneous essays treat such subjects as Ingmar Bergman, Eartha Kitt, and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton.

The impact of the writer’s early years is echoed throughout the last two parts of Black Folk Could Fly. The lens is broadened to include perspectives from the writer’s stint working in a publishing firm in New York and his travels around the U.S. in search of what it means to be Black. Biographical information appears, including an account of a prison visit to his biological father and a snapshot of his problematical relationship with his birth mother. And social commentary inevitably occurs. Kenan observes upon a return visit to his hometown, for example, that “Chinquapin was becoming more like the rest of America. It was being absorbed by the vast cultural soup of consumeristic we-think.” Miscellaneous essays treat such subjects as Ingmar Bergman, Eartha Kitt, and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton.

Each piece includes a number of digressions, often informative and diverting but sometimes producing a sprawling or disjointed effect. The essay “Where Am I Black Or, Something about My Kinfolks,” for example, starts with Chinquapin recollections, moves to a discussion of the TV series Star Trek and a defense of the genre of science fiction, returns to an account of his grandfather’s life, then jumps to a treatment of an African-American computer hacker, which leads to a reminiscence about his gradual acceptance of the world of cyberspace, then tracks the history of racial relations at Kenan’s alma mater (UNC–Chapel Hill), and concludes with a quotation from Zora Neale Hurston’s autobiography. That Kenan’s encyclopedic literary knowledge is on display here as he quotes sources ranging from alternative journalist I. F. Stone to Greek poet C. P. Cavafy doesn’t really save the essay from being desultory and inconclusive. Semantic elusiveness undermines “That Eternal Burning,” an incantatory meditation that ultimately evades meaning. A similarly unfinished quality undercuts “Chitlins and Chimichangas: A Southern Tale in Black and Latin (A Proposal for a Documentary).” Although this piece showcases Kenan’s heralded culinary interests, the essay remains just that—an unfinished attempt.

To those who argue that a volume of this nature must inevitably be uneven, I would point to the posthumous nature of the project. In the absence of the author’s guiding hand, no editor is credited. Repetitions over the course of the volume might have been excised, articles might have been dated, and the principles of selection might have been clarified. An editor’s introduction could have been added to Tayari Jones’ tribute. As it stands, the volume seems like a marketing tool capitalizing on the stellar reputation of a beloved author. Randall Kenan deserves better.

Nevertheless, the compelling power of Kenan’s prose elevates this imperfect collection. As he reminds us in “Love and Labor,” a superb essay on the writing process, “the proof is on the page.”

Anne Charles lives in Montpelier, VT. With her partner and a friend, she co-hosts the cable-access showAll Things lgbtq.