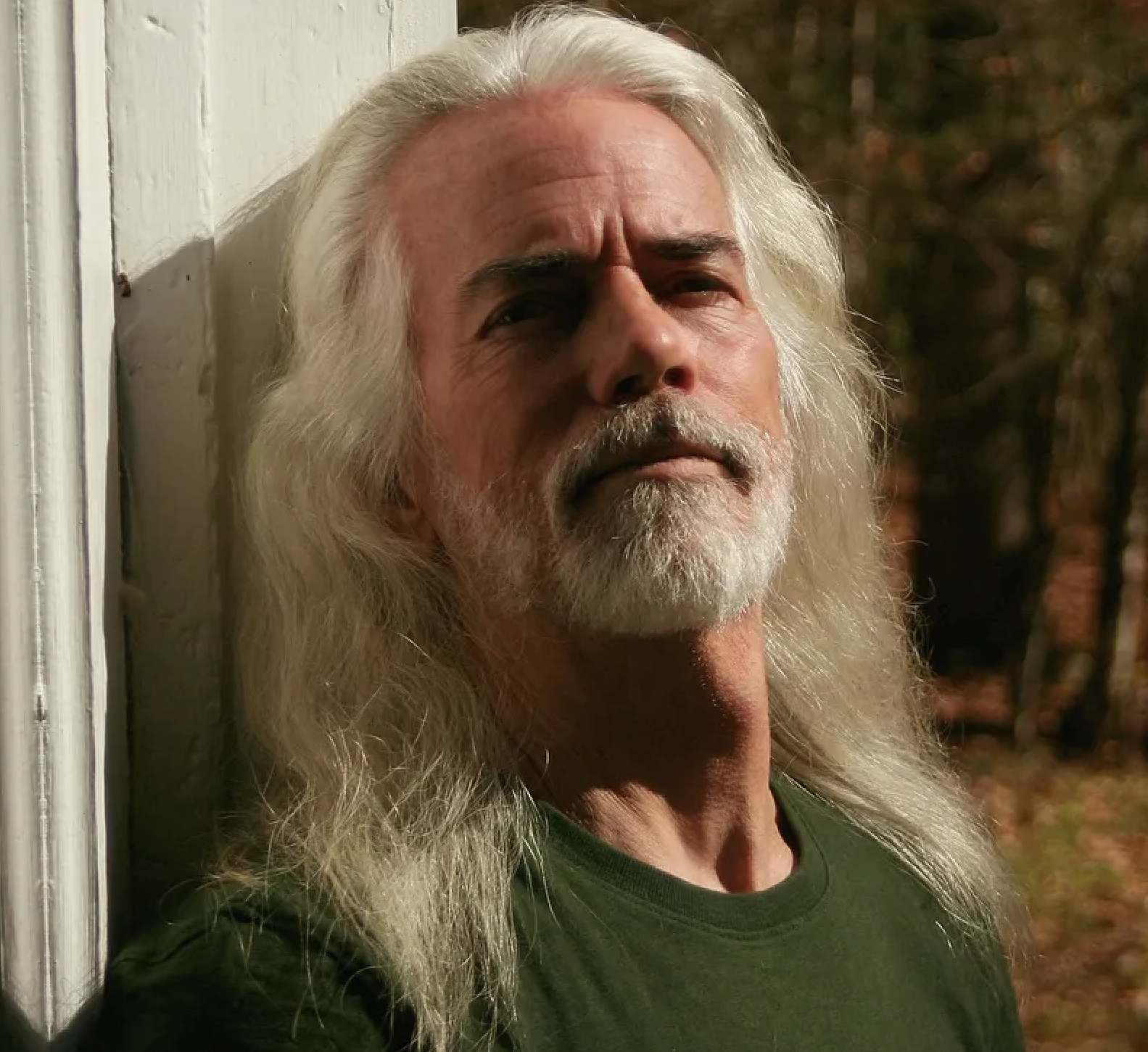

GAVIN GEOFFREY DILLARD began publishing gay poetry in the 1970s after studying poetry at the North Carolina School of the Arts, and then relocating to New York City where he befriended Allen Ginsberg, Harold Norse, Ian Young, and other gay icons of the day, before heading west to Hollywood, where he was dubbed “The Naked Poet” by The Los Angeles Times for his in-the-buff poetry readings.

He has gone on to publish ten collections of poetry (most notably The Naked Poet and Yellow Snow), two anthologies (A Day for a Lay: A Century of Gay Poetry and Between the Cracks: The Daedalus Anthology of Kinky Verse), and a provocative tell-all memoir, in the flesh (undressing for success), recounting his time in Hollywood. Dillard also wrote book and lyrics for the acclaimed BARK! The Musical, which has been staged from Anchorage to Sao Paulo to Edinburgh. He had a hit song, “The Rescue,” sung by Sam Harris and Janis Ian, and won a Frontiers Award as well as an Opera America Award for his opera When Adonis Calls, which premiered in 2015. Classical composers, starting with Jake Heggie, have set many of his poems to music.

An avid and skilled photographer, Dillard has just re-issued his poetry collection, Notes from a Marriage, first published by Felice Picano’s SeaHorse Press in 1983—this time as a photo collection—and another volume, also with photos, the elegiac Dave (due June of this year). The latest volumes can all be found at GavinDillard.org.

Trebor Healey: What poets of all stripes do you admire, and which gay poets in particular?

Gavin Geoffrey Dillard: I don’t make that distinction, generally, though bards Ian Young and Harold Norse were both friends and influencers. Beyond that, the 9th-century Japanese poet, Ono no Komachi, is my fave-rave. And Izumi Shikibu from that same period. I love Rumi and Hafiz in spurts—Mirabai as well. In these poets I found sex and romance as spiritual metaphor—something deeper and richer than I was getting from Ginsberg and others of my cadre. Mostly I read the Taoists, the River-and-Mountain poets from ages past in China. I want to hear about the trees and the clouds, the mountains, waterfalls, and a simple bowl of rice for a starving belly. I think I might have been William Blake in a past life—but shhh, that’s a secret! I’ll also confess that Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks is my singular sacred text.

GGD: Ooh, I’m the last one to ask. A Day for a Lay, my centennial anthology and paean to queer culture, was a big push for me. I’ve read very little of the genre since. I took major issue with the way gay culture handled AIDS—all our magazines sold out to Big Pharma and we became no longer the radicals I envisioned myself, but merely an economic target group. I could go on, but I’ll piss people off. Anyway, I traipsed my radical ass to the hills.

I almost exclusively read classics: Joyce, Wolfe, T.H. White, Tolkien, McCullers … and recently blew through the entire Isherwood canon—Chris was a great friend and mentor. I re-read Austen interminably—it’s a thing. Lawrence Durrell was a brilliant writer, as was Castañeda. Gore Vidal was an L.A. chum, but I’ve passed on much of his work—too much political and intellectual over romantic and heartfelt—though Myra Breckenridge was a pivot in my pre-teen years. Of course, Gore hailed Christopher as the finest writer in the English language—I cannot disagree.

I find that reading bad writing fucks up my own scribbles. The same way that reading Dickinson will keep me from writing free verse for a week. It’s like having a Blondie song stuck in your craw. I pick my writers much more carefully than I ever have my lovers. But then, a good novel lasts forever…

TH: So you’ve returned to the hills of North Carolina where you grew up. Many poets do that as they get older, and it seems a poetic homecoming. How is that going for you?

GGD: I’m a natural for Appalachia. Of course, Asheville is a hip and happening town, with terrific food, mysticism, and whatever you need. I didn’t venture too far out as I didn’t want to live amid neighbors with guns and bibles. Now I find I really don’t want to be around people with guns and bibles, so I’m looking still further out in the hills. The world is batshit crazy, but there’s an inescapable logic and exquisite, sexy, and profound simplicity (and sanity) one finds in folk who grow their own food and chop their own wood. Also, #1 on my bucket list is to hug a Sasquatch. I’ve hugged an ET (that’s another story), but I have a thing for wookies—I want to meet a real one!

Actually, I’d really like to die in a country where English is not the first language. But getting my life, in its entirety, and six cats to such a place isn’t easy—none the better for wars and plagues. So, we shall see. I find that I’ve always ended up where I’m supposed to be. But let’s not wax philosophical or we’ll cause eyes to roll. Let’s just say that I’m always awaiting my next orders.

TH: Tell me about Dave, the most recent volume (due June 21st), and this fabulous new edition of Notes from a Marriage.

GGD: Ah. Dave was the eternal lover-paradox. The angel on my shoulder, the devil-in-the-blue-dress. We couldn’t live with each other, we couldn’t live without each other. Circumstances eventually pulled us apart; my big regret is that I wasn’t with him at the end—though I believe he ended up back with his family in Florida. I do remember assisting him on a job and administering an IV antibiotic during lunch …

That said, he deserved his own book, since I shot him all the time. His life was a perpetual pose. I love the form of these two books—small, hard-bound, coffee-table editions. Simple, pretty and elegant. And they show dick unabashedly—even on the cover of Dave. My point being, as always, rawness, nakedness, intimacy, and unabashèd truth.

The Wife of Lot

Were God to take me by the hand

to my bed reserved, the Promised Land,

would he find me, wistful, gazing back,

toward smoking hills and ocean black,

Mournful of this world gone sour,

longing in that sacred hour

for one last breath of clover sweet,

a deft embrace, a swollen teat,

The eyes of lovers, insecure,

the voice of sorrow, wrath, allure,

temptation like a treasured wine

which seeps from grapes yet on the vine;

I think, all things considered be,

the Lord might have to pardon me,

that whilst that final second tolls

and angels harvest all good souls,

That I, as hearts are laid to waste,

may linger for one final taste.

Trebor Healey is the author of Falling and A Horse Called Sorrow, among other books of fiction.