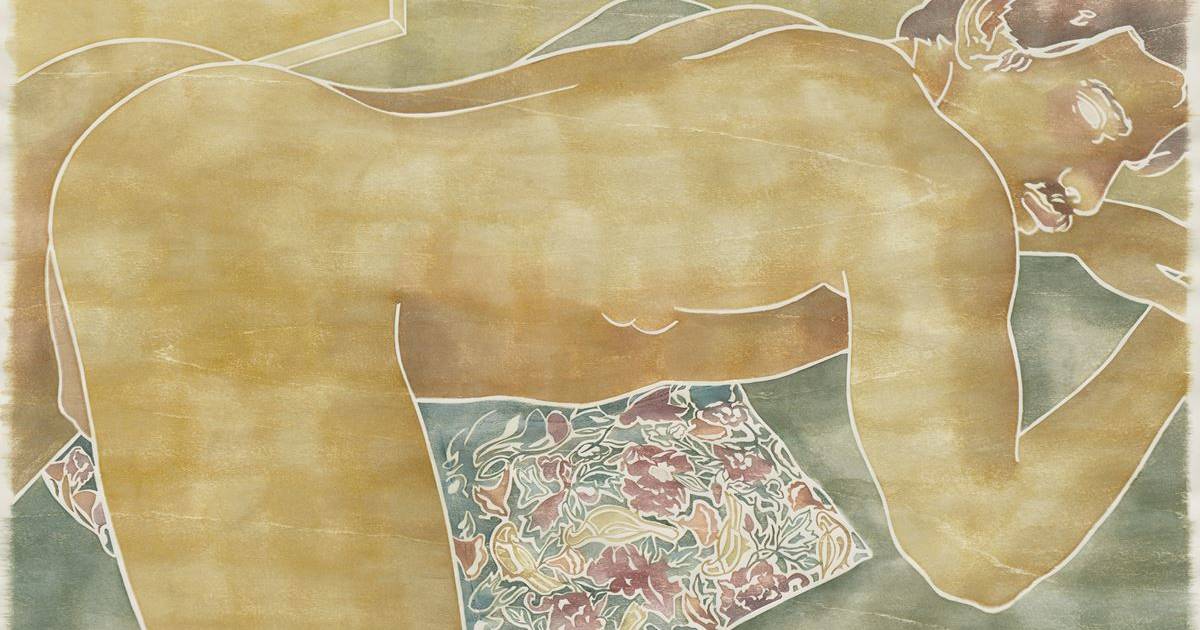

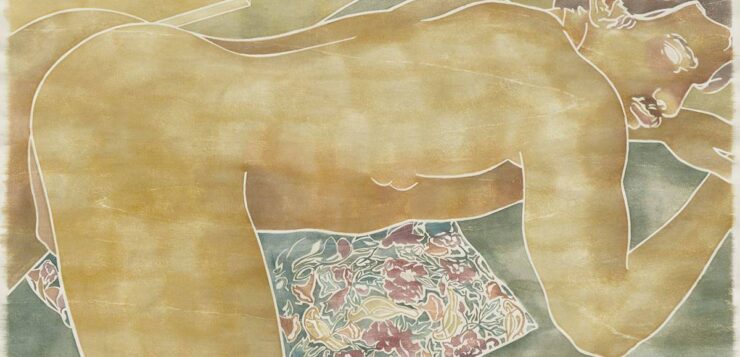

WHEN I turn the corner into the exhibition room, I try not to stare at the paintings of the naked men. It feels too obvious; not the paintings themselves but me, the gay man, stopping to examine the portrait of a model whose erection climbs his stomach to brush his belly button, or the one who balances on his elbows and knees with his ass turned in offering towards the viewer. Their posture is familiar. I have seen these poses in pornography, on Instagram, in my mirror, on my bed. My body is not one that would be found in a magazine, but these men taught me how to put it on display.

Monica Majoli, an artist and educator, created her installation for Made in L.A. 2020, a crosstown exhibition showing the work of thirty Los Angeles-based artists in two different locations. Majoli’s paintings are pulled from “Blueboys,” a series in which she paints the centerfold models of Blueboy, one of the earliest national gay magazines. The magazine’s inaugural cover parodies Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, which is on display in a gallery at the Huntington a few hundred yards from Majoli’s work. How many transmutations are present in the distance between the two buildings and the years in which the art was made? A boy becomes a painting that becomes a man in a photograph, and back again into a painting.