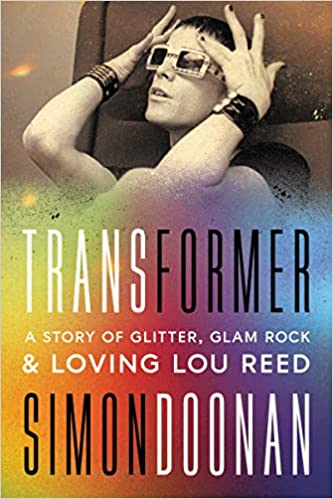

TRANSFORMER

TRANSFORMER

A Story of Glitter, Glam Rock & Loving Lou Reed

by Simon Doonan

HarperOne. 160 pages, $24.99

AS a fey young lad growing up in Reading, Berkshire, England, Simon Doonan lived with his nose buried in fashion magazines, putting on fashion shows in the attic with his sister, garbed in their mum’s clothes. One Sunday morning, Doonan’s father Terry interrupted one of the shows. “Sensing there might be a pansy among the begonias,” the elder Doonan pulled young Simon to a window with a view of Reading Gaol, the Victorian prison where a certain playwright spent two years at hard labor. “Homosexuals lead lonely lives,” he told Simon. “They get beaten up and thrown in jail, just like Oscar Wilde. They get blackmailed too. They often commit suicide.”

His father’s warning did nothing to deter the fashion-obsessed teenager, who came of age in the Swinging Sixties, from “aggressively pursuing fabulosity, fashion, and music.” He became obsessed with early ’70s glam rock, especially that of David Bowie and his “Spider from Mars” guitarist Mick Ronson. In an interview with Bowie, Simon learned about Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground, and his obsessions grew to include Lou Reed.

Doonan writes that the year 1972 was pivotal not only in his life but for social change in general. “The counter-culture of the late ‘60s [had]loosened up the stays of midcentury respectability. … Notions of sexual liberation, gender equality, androgyny, camp, unisex style, [and]bisexuality are endlessly dissected.” That year, Sweden became the first country to legalize gender-affirming surgery, San Francisco outlawed employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and London held its first Gay Pride parade. The time was ripe, Doonan writes, for hitherto unimaginable change. For Doonan, two seminal albums appeared that year: Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and Lou Reed’s Transformer.

Simon Doonan’s Transformer is a light-hearted, deeply personal, thoroughly researched examination of the social and artistic revolution in fashion and music ushered in during the 1960s and ’70s, and the role of Transformer in that revolution. Along the way, Doonan sheds light on the notion of “camp” (and Susan Sontag’s provocative Notes on Camp); the influences of Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and the Factory on art, music, and social mores; the history and omnipresence of drag in Britain and the U.S.; the role played by Warhol “superstars” Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and others in the creation of Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side”; Reed’s history of electro-shock therapy, drug dependency, poetic aspirations, and bad marriages; and the reactions of both gays and “hets” to Reed’s best-selling album. It is a slim volume, but it’s packed with intelligent analysis and Doonan’s trademark humor.

Simon Doonan’s Transformer is a light-hearted, deeply personal, thoroughly researched examination of the social and artistic revolution in fashion and music ushered in during the 1960s and ’70s, and the role of Transformer in that revolution. Along the way, Doonan sheds light on the notion of “camp” (and Susan Sontag’s provocative Notes on Camp); the influences of Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and the Factory on art, music, and social mores; the history and omnipresence of drag in Britain and the U.S.; the role played by Warhol “superstars” Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and others in the creation of Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side”; Reed’s history of electro-shock therapy, drug dependency, poetic aspirations, and bad marriages; and the reactions of both gays and “hets” to Reed’s best-selling album. It is a slim volume, but it’s packed with intelligent analysis and Doonan’s trademark humor.

After moving to New York and becoming the window dresser (and later creative director) at Barney’s, Doonan immersed himself in the nightlife, becoming a regular fixture at Max’s Kansas City and the Factory. Getting to know Andy’s superstars, he developed a deep appreciation for drag: “Drag takes so much effort and commitment—if you have any doubts, try ‘tucking’ with duct tape and get back to me—it is safe to assume that the motivations are many and various.” These include gender expression, survival, revenge, a desire for attention (“those girls wanted to be gawked at and desired and unconditionally worshipped”), and money. “Drag is a power grab of the otherwise powerless. Drag is a money grab of the otherwise broke. … Holly, Candy, and Jackie … were no strangers to financial desperation.”

When Lou Reed encountered drag queens in New York, Doonan writes, drag was “transgressive, clandestine, taboo, and fun.” He celebrates the superstars’ fixation on Hollywood glamor: Candy Darling went “directly from grim boyhood—a violent drunken dad and bullying schoolmates—to Hollywood movie star, female.” He agrees with Warhol’s assessment that “Jackie Curtis is not a drag queen; Jackie is an artist. A pioneer without a frontier.” Holly Woodlawn, he writes, “vibrates with manic, drug-fueled conviction … a stomping tour de force of feminine self-belief.” Their influence on the album Transformer cannot be overstated.

After examining all the background that informs Transformer, Doonan takes us on a track-by-track trip through the album. In the opening song, “Vicious,” he finds a touch of delightfully campy badinage on a par with “the relentlessly bitchy queens in The Boys in the Band,” with the two characters in the song swatting each other with flowers. “Andy’s Chest,” he tells us, was written in response to Valerie Solanas’ shooting of Warhol. He briefly dissects other tracks on the album but saves most of his surgical skill for “by far the most significant cut” on the album, “Walk on the Wild Side.”

The characters who are name-checked in the latter song are Warhol superstars. Besides Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, and Jackie Curtis, there’s Joe Dallesandro and Joe Campbell (a Warhol actor known as “Sugar Plum Fairy,” ex-boyfriend of gay icon Harvey Milk). Doonan finds the core of this song in “the electrifying juxtaposition between the sordid screenplay of Lou’s poetry [Candy ‘never lost her head even when she was giving head’] … and the sumptuous musical arrangement. It’s like a corpse in a satin-lined coffin.” Reed’s sordid images couched in the soaring arrangement thus elevated the lives of these characters to the level of romantic, campy myth. For readers who appreciate the minutiae of how a record is produced, Doonan explains how Ken Scott (who did the final mix on the song) incorporated the “doo-de-doo-de-doos” sung by the three girls in the group Thunderthighs. Scott and Reed were somewhat bored with the repetitiveness of the chorus. So, in order to mix things up, Scott asked the girls to start at a distance from the microphone, walking toward it as they sang, to simulate hearing the girls walking toward you on a Manhattan street, their voices getting louder with each step of their walk on the wild side.

“The song is ultimately a hymn to visibility,” Doonan writes. The critics, however, were having none of it. Rock ’n’ roll critics, especially in the U.S., brutally scorched the album, filling their critiques with homophobic dog-whistles, as if to ask: How dare those faggy freaky glamazons Bowie and Ronson co-opt our classic rocker Lou Reed? Ellen Willis in The New Yorker blasted the album as “lame, pseudo-decadent lyrics, lame, pseudo-something-or-other singing, and a just plain lame band.” Even Lou Reed came to hate the album and retreated from his androgynous glam rock persona.

Despite the critics’ lambasting Transformer, the new century brought a deeper, fuller appreciation of the album. It regularly appears high on several magazines’ and critics’ list of the greatest albums of all time. And, of course, the centerpiece of the album, “Walk on the Wild Side,” still plays on radio stations around the world. Doonan’s book is a serious yet campy homage to the very first explicitly, purposely queer-oriented music album. In addition to being a funny, fact-filled history, the book sent me back to listen more intently to the album and led me to the conclusion that Transformer is indeed a glamdrogynous (Doonan’s coinage) masterpiece.

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.