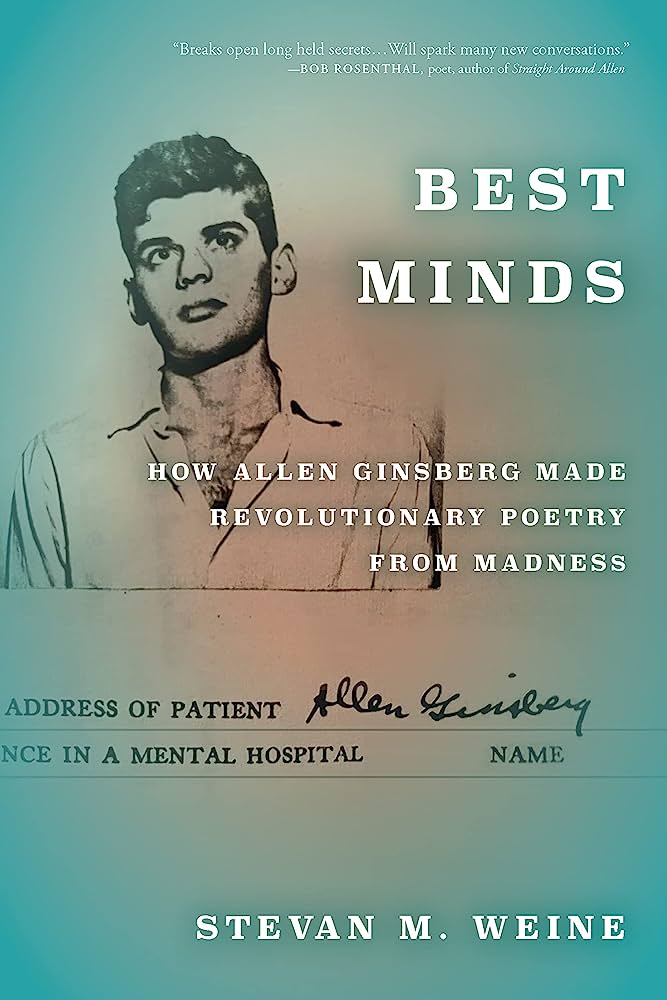

BEST MINDS

BEST MINDS

How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness

by Stevan M. Weine

Fordham U. Press. 304 pages, $34.95

AS A THIRD-YEAR medical student at Columbia in the mid-1980s, Stevan M. Weine wrote to his hero, Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997), wanting to pursue research on Ginsberg’s experiences with mental illness. The poet welcomed Weine’s interest and gave him access to his medical records from his eight-month stay at a psychiatric hospital (1949–1950). Weine, now a professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, thought the author of “Howl” and “Kaddish” could help him understand “the relationships, if any, between madness and poetry, between art and life.” Published more than three decades after their first meeting, Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness reveals what Weine learned from and about the Beat poet and counterculture spokesman who became his friend and mentor. The book combines biography, medical history, literary analysis, and memoir. It feels jumbled in places, with the narrative moving back and forth in time, but Ginsberg’s long reckoning with mental illness deserves the sustained and sympathetic attention that Weine provides.

Born in Newark, Ginsberg grew up in Paterson, New Jersey, the younger son of Louis and Naomi Ginsberg. His mother, a Russian immigrant who graduated from college and worked as a schoolteacher, was periodically institutionalized for schizophrenia throughout his childhood, and his parents eventually divorced. In November 1947, when Ginsberg was a 21-year-old English major at Columbia—reading widely, getting to know other ambitious young writers, and fretting over his sexuality—he granted doctors at New York’s Pilgrim State Hospital permission to perform a prefrontal lobotomy on Naomi. Two months later, she had the ghoulish procedure. In time, based on apparent improvement, she was allowed to leave the asylum, a massive complex housing more than 13,000 patients. However, she continued to suffer and caused distress for everyone around her, which led her to be institutionalized again.

In May 1948, six months after he gave the doctors permission to lobotomize his mother, Ginsberg began having what he called visions. While reading William Blake’s poetry in bed in his East Harlem apartment, he heard a disembodied, “ancient” voice reciting the poems. The apprentice poet felt he was in God’s presence and experienced a profound contentment and acceptance of the universe. Most accounts of this formative incident report that Ginsberg heard Blake himself reading the poems. According to Weine’s research, it was actually ten years after his visionary experience that Ginsberg began identifying the voice as Blake’s.

Exciting as his visions (including one in the university bookstore) were at the time, Ginsberg still had to function in the quotidian world. Distracted and worried that he was going mad just like his mother, he struggled. In the spring of 1949, he allowed several thieves, including his impoverished junkie pal and poetic muse Herbert Huncke, to store their loot in his apartment. When they were caught, Ginsberg’s father, a respected poet and teacher, along with several of Allen’s Columbia professors, intervened on behalf of the troubled young man who clearly wasn’t in the same category as the crooks he’d befriended. As a result, Ginsberg was sent not to prison but to the New York State Psychiatric Institute for treatment and rehabilitation. It was there that Ginsberg met fellow patient Carl Solomon, an erudite gay man with whom he quickly bonded and later immortalized in “Howl,” the long title poem of his debut collection, Howl and Other Poems (1956).

The most intriguing parts of Best Minds appear in the prologue and the chapter describing Ginsberg’s eight months in the asylum. Near the end of his stay, during the hospital’s weekly case conference, he appeared on stage with his therapist for an interview in front of an audience of hospital staff. Weine summarizes the notes in Ginsberg’s medical file: “The patient acted as if he had something to prove—that he wasn’t mad like his mother, who had recently been released from Pilgrim State Hospital following a several-year stay and a prefrontal lobotomy. He was talkative and brash but cooperative and aware of the audience around him. … He was grandiose, like many people in the throes of psychosis, but also demonstrated literary talents and ambitions not commonly seen among the patients presented at the clinical case conference.”

After Ginsberg left the auditorium, the doctors conferred, and the hospital’s chief of service, Dr. Nolan Lewis, gave his pronouncement: “The patient was a severe schizoid, who would probably go definitely schizophrenic someday, but was near genius level in creating.” In an interesting twist, Ginsberg apparently was not informed of his prognosis. His time in a mental institution proved to be restorative, providing him with valuable material for “Howl,” his most famous poem.

The title of Weine’s book comes from the first line of “Howl”: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked.” With that memorable opening, Weine argues, Ginsberg “opened up a space for telling an entirely new story about the generation coming of age in postwar America. He had been gathering and digesting these stories for years, stories that spoke to many sides of madness. He had been making his way toward adopting the voice and perspective of a witness to madness.”

Weine makes a similarly eloquent case for “Kaddish,” Ginsberg’s masterpiece eulogizing his mother. Naomi Ginsberg died at Pilgrim State Hospital on June 9, 1956. Allen Ginsberg, by now launched as a poet and living in San Francisco with his boyfriend Peter Orlovsky, chose not to return East for the funeral. Years later, he said he forgot why he didn’t go. For lack of sufficient mourners at her funeral, Naomi was not memorialized with a Kaddish, the traditional Jewish prayer for the dead. In “Kaddish,” he gave her his version of the prayer that she didn’t have at her funeral. The title poem of a collection he published in 1961, “Kaddish” offers a much darker, sadder view of the madness Ginsberg champions in “Howl” and contains graphic descriptions of his desperately ill mother. As Weine observes: “‘Kaddish’ staked out harrowing new landscapes in imagining and engaging real-world suffering, conflict, injustice, traumas, and death, in an empowering narrative of witness.”

Best Minds follows the poet through his rise to countercultural stardom in the 1960s and after. It touches on Ginsberg’s close relationship with Orlovsky, who was addicted to drugs—a complicated bond that warrants more attention than it receives in the book. Weine acknowledges that Ginsberg was no saint (as the poet’s defiant membership in the North American Man/ Boy Love Association makes clear), but his faith in his mentor remains steadfast. Looking back on what he learned from Ginsberg, he declares that the poet’s “radical acceptance of madness as a basic human capacity, which includes the potential for good, invites us to change how we understand madness and mental illness and is itself another powerful way of expanding consciousness for the benefit of humankind.”

Hilary Holladay is the author of The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography and Herbert Huncke: The Times Square Hustler Who Inspired Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation.