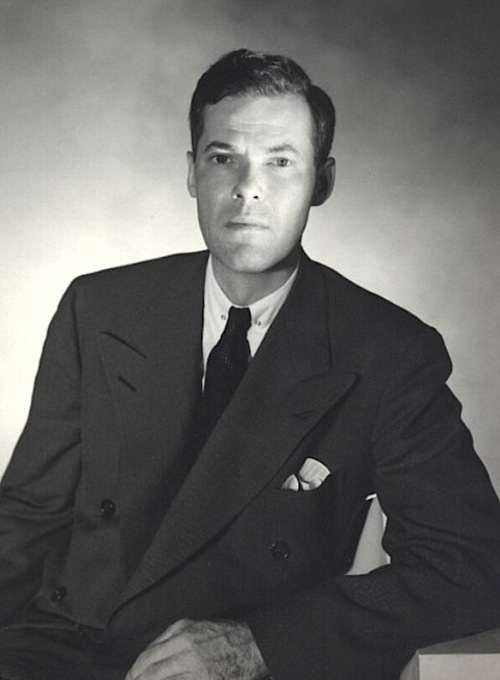

A Heaven of Words: Last Journals, 1956-1981

A Heaven of Words: Last Journals, 1956-1981

by Glenway Wescott

Edited by Jerry Rosco

Univ. of Wisconsin. 314 pages, $24.95

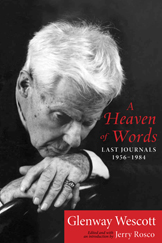

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories

by Glenway Wescott

Edited by Jerry Rosco

Univ. of Wisconsin. 200 pages, $26.95

SAY THE NAME “Glenway Wescott” at a cocktail party or gay studies conference and most people will draw a blank (“Glenway Who?”). But every so often someone may dimly recollect this 1920s expatriate American writer based in Paris whose early autobiographical works from his haunted Midwest youth, such as The Grandmothers and Goodbye, Wisconsin, placed him in the same respected company as Hemingway—for a time. Alas, his later output was limited, though it did include The Pilgrim Hawk, a short novel which was lauded by the estimable Susan Sontag as “among the treasures of 20th-century American literature.” Edmund White wrote a sympathetic assessment of Wescott in The New York Review of Books a number of years ago, and two current books from the University of Wisconsin Press may herald a revival.

Others may know of Wescott less for his literary output than for his gay life and social circle, which included a lifelong intimacy with Monroe Wheeler, book and exhibition designer for New York’s Museum of Modern Art, whom he’d met at the University of Chicago. This connection was sexually sidelined relatively early in their partnership by the arrival of the young and beautiful George Platt Lynes, an upstart æsthete at the time but destined to become famous as a celebrity and dance photographer from the 1930s to the ’50s. His posthumous gay fame comes largely from his wealth of male nude images. Wescott endured the new arrangement—a painful one, since he, too, was enamored of Lynes. The handsome trio was presented in a stylish 1998 illustrated book by Arena Editions, When We Were Three, based on travel albums that covered their European jaunts from 1925 to 1935.

My sense, however, is that Wescott (1901-1987) remains a problematic writer for our times, and this is too bad. His language is highly considered in a way foreign to our colloquial age. His sensibility engages emotional restraint at a time when letting it all hang out is de rigueur. He began as a poet, among Yvor Winters and other Imagists like H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and Mina Loy, and he forever retained an attention to words, one by one, which slowed his facility as a novelist and can give his writing a studied quality. In his new introduction to Wescott’s late journals which he edited, Jerry Rosco, author of the 2002 book Glenway Wescott Personally: A Biography, comments that “his elegant lyrical prose seems more Continental than American”—which I take to mean that while Wescott came from the heartland, his style was more ornate than plain-spoken.

This seems to have been recognized in his own time. When they were both expatriates vying for literary status, Hemingway, already antipathetic to the gay Wescott, sneered of The Grandmothers that “every sentence was written with the intention of making Glenway Wescott immortal.” For those interested in games of literary one-upmanship, it helps to know that Hemingway’s mother once suggested that her son should write more like Mr. Wescott. Instead, Hemingway included a quick, unflattering portrait of Wescott in The Sun Also Rises and once complained to his editor Maxwell Perkins that other writers were getting rich—he named Wescott, Thornton Wilder, and Julian Green, all homosexuals—while he was “the only one with wives and children to support.” This story is valuable for confirming Wescott’s place among the expatriate writers in Lost Generation Paris.

This seems to have been recognized in his own time. When they were both expatriates vying for literary status, Hemingway, already antipathetic to the gay Wescott, sneered of The Grandmothers that “every sentence was written with the intention of making Glenway Wescott immortal.” For those interested in games of literary one-upmanship, it helps to know that Hemingway’s mother once suggested that her son should write more like Mr. Wescott. Instead, Hemingway included a quick, unflattering portrait of Wescott in The Sun Also Rises and once complained to his editor Maxwell Perkins that other writers were getting rich—he named Wescott, Thornton Wilder, and Julian Green, all homosexuals—while he was “the only one with wives and children to support.” This story is valuable for confirming Wescott’s place among the expatriate writers in Lost Generation Paris.

By the 1930s, Wescott’s output slowed; he suffered long bouts of writer’s block. However, he returned in rare commercial form in 1944 with Apartment in Athens, a tense psychological thriller in which an impoverished Greek couple living under Nazi occupation in the capital city with their two children must quarter a German officer. In the event, they can betray no emotion, but abjectly cower under his every whim while answering to his needs with blank servility. So skillful is the narrative’s emotional cat-and-mouse that the book was a bestseller, and popular enough to be made available to servicemen in a wartime miniature pocket edition. Later, Wescott continued to be a respected commentator on the literary scene, supporting and advocating the work of other writers. His collection Images of Truth (1962) contains trenchant profiles of six fellow novelists: Katherine Anne Porter, W. Somerset Maugham, Colette, Isak Dinesen, Thomas Mann, and Thornton Wilder.

So, now we have two volumes from the University of Wisconsin presenting substantially new material that allows us to see Wescott in a fresh light. Rosco, who completed the editorial work begun by Robert Phelps on Wescott’s first diaries, Continual Lessons, covering the years 1937 to 1955 (and ending with Lynes’ early death), brings us the second and final volume, A Heaven of Words, Wescott’s commentaries from 1956 to 1981. Rosco has also put together a collection of short fiction by Wescott featuring a barely known homoerotic tale which is the book’s title piece in A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories, along with a well-chosen mix of unpublished or previously anthologized works.

Given the span of years covered by the short story collection, this approach has the virtue of introducing new readers both to early signature pieces like the psychologically intense and autobiographical “The Babe’s Bed” (1929) and to virgin material like “The Stallions,” a strangely fascinating account of horse breeding which seems to be about more than animal husbandry and was originally planned for expansion into a novella. Another new arrival is “An Example of Suicide” of 1938, based on “a sensational news event” of that year. A young bank clerk threatened to jump from a window ledge of the Hotel Gotham, and the city held its collective breath. Wescott entered the despairing mindset of such a young man while waiting for the comforting return of his own domestic companion (Wheeler). The story was found in manuscript among the Wescott papers.

Some readers may worry that a writer’s late diaries could be difficult to understand without first consulting the earlier ones, but Rosco’s editorial frame is especially helpful on that score. He first writes an overall introduction to A Heaven of Words that delineates the broad outlines of Wescott’s personal and professional life. He then breaks up the 28 years of journal entries into blocks of time and provides short but helpful overviews for each period. These tell us what was taking place in Wescott’s life and career during each of these four- or five-year stretches, sometimes previewing key moments and giving the reader helpful signposts.

In the final analysis, however, it is Wescott’s private musings—about art and the travails of the writing life, about losing the country home that he once shared with Wheeler and Lynes, about sex, aging, and health problems within his family—that strike to the heart by their simplicity and directness. And we learn about his wide-ranging circle of friends—prominent ones like “Willie” Somerset Maugham and Katherine Anne Porter; intimate ones like John Connolly—and about his abiding devotion to Wheeler, which plucks the heartstrings. These journals present a Wescott style that is variously terse, piquant, and emotionally naked. This is quite different from the earlier entries of Continual Lessons, written in lengthy passages rather than these staccato fragments.

As a record of both literary and gay life in the mid-century decades, the journals offer a caustic, though never entirely bitchy, glimpse into the lives of the gay and famous. At one of his own dinner parties, Wescott is eager to regale his guests with stories about Jean Cocteau and to put questions to the composer and (all too candid) diarist Ned Rorem, “but Truman Capote shouted me down all evening, in his falsetto way, about various crimes and atrocities.” This was, after all, the period of In Cold Blood. “As it happens,” continued Wescott, “I have never been with him in all-male society before, and was astonished to find that the subject matter of sex doesn’t interest him at all.” And when one of President Johnson’s aides, “the father of six children,” resigns after “having been arrested for indecent behavior in the men’s room of the notorious Washington YMCA,” Wescott wonders: “Will foolish homosexual or ambi-sexual men never cease to involve themselves in public service careers? I suppose the danger of the risks they run excites them—just as the men’s room surreptitiousness, the voyeurism, the exhibitionism, intensifies their desire.”

In a more domestic vein, the delights and vexations of friends and family, including his brother Lloyd and sister-in-law Barbara Harrison—an heiress whose largesse made it possible for Wescott to live near them on country property in New Jersey—figure prominently in these accounts. Apart from this material, Wescott’s writings on nature nearly always provided him with solace, and the sympathetic reader will share this as well. A simple and brief entry from 1959: “A young hawk visited me, not gyring for food but flying straight across very like a speed-boat, but in magical silence, just over the rooftops—I loved him.”

Wescott managed to know just about every writer of his generation, especially since he served as president of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and he was a social creature inhabiting a very heady society. Thus A Heaven of Words is a feast of dropped names and social events. Here are Sal Mineo and playwright William Inge at a dinner party, or Baron Philippe and Baroness Pauline de Rothschild—two extremely close friends who made his later trips to France possible—and Jean Cocteau, Colette, George Balanchine, Isak Dinesen, or Dr. Alfred Kinsey at various times and places.

Switching to A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories, we find ourselves alternately delighted and vexed, for Wescott can be psychologically astute, yet often he’s at pains to slice layers of meaning in human motivation and action as thinly as possible while failing to deliver any plot momentum. The title story—properly speaking, an autobiographical meditation—feels less an easy pleasure than a task with intermittent rewards. Wescott is taking a trip to Maine and a friend has recommended that he meet up with a young painter and “pseudo-intellectual” named Hawthorn (surely a pseudonym; perhaps also a literary joke?) with a “sex so monstrously large that sexual intercourse with him is practically impossible.” This could be an occasion for comic ribaldry, but as “Priapus” is an account from his life in the year 1938, Wescott is determined to analyze every gesture the young man makes. The eventual sexual action Wescott describes at ponderous length—a long, unsatisfying night of lovemaking so decorously detailed that the reader may not be sure what actually happened. Wescott concludes that the young man is already planning continued relations as future occasions might permit: “He wished to compromise me, to engage me in a kind of collusion in the matter of his physical insensibility to me. He wished to feel free to disappoint me, if need be; and to be sincerely surprised by and resentful of my disappointment if I should so far forget myself as to voice any.”

“A Visit to Priapus” neither takes joy in the improbable nor exudes much sympathy for a young man more afflicted than gifted. It has neither the verbal energy of pornography—which would not have been Wescott’s style in any case—nor elegant aperçus on love and sex that might lend it a bracing freshness. It is not without interesting moments, however, especially as an archæology of the Wescott-Wheeler-Lynes circle’s modus vivendi, where it offers precious glimpses of sexual roundelays shared within their cosmopolitan milieu.

Other stories and essays in the collection are briefer, yet finally more pungent. “The Babe’s Bed” is an important introduction to Wescott’s autobiographical doppelganger, Alwyn Tower, an expatriate writer who returns home to the family farm in Wisconsin in the midst of the Depression. Some stories exhibit Wescott’s unstated political sympathies. In “Mr. Auerbach in Paris,” he recalls his first trip to the French capital in 1923 in the company of his German-American employer, a cultivated Jew who regrets the German defeat in the First World War and displays an alarming German chauvinism. Auerbach thinks Paris would be “the greatest city in the world too if the Germans had it. … Because France … is a sensual, effeminate, idle, decadent nation. The Germans are superior to them.”

Among the most emotionally trenchant pieces is the personal essay “The Valley Submerged”—half memoir, half philosophical rumination. It is haunted by the memory of Wescott’s first country home, Stone-blossom, shared for years with Wheeler and Lynes, which was expropriated by the state of New Jersey and submerged under water to build a reservoir. Reviewing the year of its demise, 1957, Wescott recollects that he “resolved … for the remainder of my tenure of the doomed house … to keep track of the time of the sunrise and set my clock accordingly, so as to allow myself ten minutes of vigil.” Twenty years later: “I haven’t forgotten, and I expect never to forget the exact way the sunrise appeared in my bedroom window there.”

Wescott died a year before Monroe Wheeler; they had been companions together for nearly seventy years.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph and a frequent contributor to this magazine.