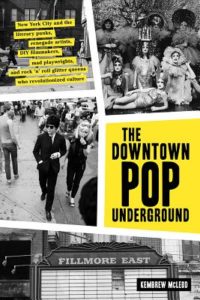

The Downtown Pop Underground

The Downtown Pop Underground

by Kembrew McLeod

Abrams Press. 361 pages, $27.

THERE ARE several strands running through Kembrew McLeod’s tumultuous history of the art scene in lower Manhattan from the 1960s to the late ’70s—a scene that McLeod believes has had an outsize influence on American and global culture. He starts with the mostly gay playwrights who got their first plays performed at a coffeehouse in the West Village called Caffe Cino, segues to Andy Warhol’s movies, underground publications like Fuck You / A Magazine of the Arts, the new technology of the video camera, television, and finally the rise of punk rock. But the gay playwrights who started out on Cornelia Street at Caffe Cino are the most fascinating.

Caffe Cino flourished at a time when there were still Italians in Little Italy, when women leaned on pillows on their windowsills to watch what was going on in the street below, when people threw their keys down to the pavement to let visitors in, when homeless men on the Bowery set trash cans on fire in winter to stay warm (and sometimes expired on the sidewalk), and glitter was crucial to drag queens and theater. It was a time when New York was on the skids, and rent was very cheap—though not cheap enough for playwright Harry Koutoukas, who would, when bills arrived that he couldn’t pay, stamp deceased on them and send them back.

Several of the Caffe Cino playwrights—William Hoffman, Lanford Wilson, Robert Patrick, Harvey Fierstein—went on to achieve success on Broadway. Tom O’Horgan had a huge hit directing the musical Hair. But when they were just starting out, what they were doing really resembled one of those Judy Garland–Mickey Rooney musicals in which a bunch of kids decide to put on a play—not in a barn, in this case, but at a coffeehouse run by a gay man named Joe Cino. This is where Lanford Wilson’s The Madness of Lady Bright was first produced, and Robert Patrick’s The Haunted Host. Both plays star loquacious queens in their apartments—the first going mad, the second entertaining an innocent caller. Sometimes the settings were more grandiose. Harry Koutoukas’ Tidy Passions, for example, opened with a one-line homage to Allen Ginsberg’s Howl: “I have seen the best cobras of my generation die mad—from lack of worship. … Ancient temple music UP.”

These plays were put on not only in the Caffe Cino, but also in places like the Mercer Arts Center (until the derelict hotel adjacent to it collapsed), the Judson Memorial Church, and La Mama—all of which became what was called “Off-Off Broadway.” They were all done with very little in the way of theatrical production values; in fact, an amateurish tone was key. (Script directions for Tidy Passions: “It is vital that no part of the setting or costumes be bought, the designer of the costumes and sets must spin them of remnants and castaway items.”) And they all had campy titles like Women Behind Bars, The Vicissitudes of the Damned, Miss Nefertiti Regrets, Journey to the Center of Uranus, Conquest of the Universe, In Search of the Cobra Jewels, Cock-Strong, and, my favorite for some reason, Too Late for Yogurt.

In the larger scheme of things, this book tracks the mostly gay history of Greenwich Village between the Beatniks (Ginsberg, Kerouac) and the rise of punk rock (the Ramones, Blondie). Stonewall is but a blip in this tale. More important landmarks are: Andy Warhol’s Factory, the Cockettes’ infamous appearance in New York, the PBS show An American Family, the nightclubs Max’s Kansas City and CBGB, and Blondie’s “Heart of Glass.” The people we follow include Patti Smith, Sam Shepard, David Bowie, Lou Reed, John Waters, Valerie Solanas (the woman who shot Warhol), Hibiscus (of the Cockettes and the Angels of Light), the triumvirate of drag queens Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, and Holly Woodlawn, and a host of characters that most people have never heard of unless they lived in the Village at that time. Doric Wilson does not appear for some reason, and playwright Charles Ludlam is hardly mentioned (the Caffe Cino actors thought him too traditional).

It is hard to say who presides over the book, but if one had to choose a figure, it would probably be Warhol, even when he’s offstage. Warhol and his Factory are a constant presence, like a flying saucer from a sinister planet in one of the plays that were put on at John Vaccaro’s Play-house of the Ridiculous.

Vaccaro and Charles Ludlam fell out while Vaccaro was directing a script of Ludlam’s called Conquest of the Universe. After they split, Ludlam rewrote the script for his own theater troupe and called the play When Queens Collide, which could be the subtitle for this book. The Caffe Cino crowd had highly combustible egos, but they did share one thing: a do-it-yourself approach to the arts—i.e., you didn’t have to know how to play the guitar to start a rock band, or be an actor to star in a play, or work in the movie business to make a movie. “Don’t be an ac-TOR,” Vaccaro would say to make fun of Method acting. They all knew they were amateurs. (The macho Abstract Expressionists who met at the Cedar Tavern considered even Warhol “a little fairy commercial illustrator.”) At the same time, they were highly ambitious—“driven” is the word used for both Patti Smith and Debbie Harry—though their method was to mock what you dreamt of being: a star. And they were all fleeing something: families, small towns, homophobia, New Jersey. As one of the early punk rockers discovered when they first saw the New York Dolls at the Hotel Diplomat: “We just knew right then and there that there was a place that we could feel like we can express ourself without feeling like an outcast.”

There was a difference between the drag queens on Cornelia Street and the Factory crowd, but because McLeod does not editorialize, it’s left to the reader to ascertain just what it was. When playwright Robert Heide met Harry Koutoukas, they were both walking around the Village with a copy of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. The Factory was less intellectual, and much edgier. It wasn’t just the amphetamines the Factory actors brought with them to the Cino or the speed that Factory star Ondine injected into his dick in the bathroom during rehearsals. The Cino playwrights really do seem to have been like Garland and Rooney putting on a musical. What they had was the chutzpah of nonentities, of people who had nothing to lose—though they had their dark side too. John Vaccaro had, according to Penny Arcade, “a really apocalyptic vision of the world in the middle of peace, love and happiness, but New York was not a place of peace, love and happiness in the sixties.” Indeed, during one performance at La Mama, where many of the Cino playwrights gravitated after the Caffe closed, Harry Koutoukas took out a razor and began slitting his wrists while everyone froze in horror. “Oh,” he said when the other actors finally walked off, “are you going to condemn me for getting blood on the stage?” There was enough nihilism in both crowds to go around.

McLeod’s point that these “denizens of downtown … transformed culture on a national and global scale” is persuasive. When one reads of a “happening” (a ’60s term) on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, one thinks of ACT UP and Occupy Wall Street. The production that Tom O’Horgan directed of Paul Foster’s play Tom Paine was years before Hamilton, just as his production of Hair prefigured Rent. An American Family was the first of many reality shows, including, alas, The Apprentice. What’s new?

Attitudes toward homosexuality, for one thing. It is shocking to read Anne Roiphe’s claim in The New York Times that Lance Loud’s “flamboyant, leechlike homosexuality” meant that this “evil flower of the Loud family, dominates the drama—the devil always has the best lines.” As for his mother Pat: “She is confronted, brutally and without preparation, with the transvestite, perverse world of hustlers, drug addicts, pushers, etc., and watches her son prance through a society that can be barely comprehensible to a forty-five-year-old woman from Santa Barbara.” But then a main motive of the downtown pop scene was, and always will be, épater le bourgeoisie. People in the audience at NYU threw up when Wayne/Jayne County ate shit (dog food, actually) while singing a song called “Toilet Love.” The desire to shock was a huge element in all of this. As John Waters put it: “I made all of my movies to offend hippies.”

McLEOD, now a professor at the University of Iowa, fell in love with the New York underground while working on a play in high school by Patti Smith and Sam Shepard called Cowboy Mouth, and his book is a sort of torrent of anecdotes, assembled with the enthusiasm of the true fan. But he doesn’t shy away from the underside of drug use and violence that ran through this subculture. There was something creepy about the fact that, as someone pointed out, Warhol himself did not do drugs but encouraged other people to do them (like the beautiful but doomed actress Edie Sedgwick). “There was always the sense that something could go terribly wrong at the Factory,” Robert Heide recalls, like the time in the fall of 1964 when a woman named Dorothy Podber “walked into the Factory with her Great Dane named Carmen Miranda, motioned to the Monroe silkscreens, and asked, ‘Can I shoot those?’ Warhol said yes—assuming that Podber was going to take a picture—but she instead pulled out a pistol and shot a hole through the canvases.”

In 1964, the scene darkened when a dancer named Freddie Herko, who was taking too much LSD, went to a friend’s apartment, put on Mozart’s Great Mass in C, and danced right out the fifth-floor window to his death. After asking Robert Heide to point out the spot on the sidewalk where the body had landed, Warhol looked up at the window and said: “I wonder when Edie will commit suicide. I hope she lets us know so we could film it.” What is one to make of such a statement? McLeod lets a woman who’d grown up in the Village at that time explain that it was “Andy’s way of processing” Herko’s death. “Because at that time to show emotion, none of that was acceptable for men in that age. I mean, cool was the number one thing. It was a thing that was very prominent in the Village, a kind of game that the bohemians would play.”

The camp humor that lay at the center of the drag queens and gay playwrights’ work could be cutting and cruel, but it was the concept of cool—the blank face of Warhol, the “Gee” and “Golly” with which he responded to things, the faux innocence—that separated the Cino crowd from the Factory. It was, you might say, the difference between the ’60s and the ’70s. Even though Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn were part of the back room at Max’s Kansas City over which Warhol presided, they were somehow a lot sweeter than the Factory crowd. Candy Darling, whom rich people uptown would pay five hundred bucks to go to their parties (for a touch of bohemian chic), was a small-time player compared to Warhol and his business manager Fred Hughes, who began charging society people thousands of dollars for a portrait. After Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas, he withdrew from the downtown scene and began concentrating on the rich and famous. There is a real tension between downtown and uptown in this story, and only Warhol made the transition, stepping back from the violence downtown only to die years later of a nurse’s incompetence while recuperating overnight from gall bladder surgery in a hospital on the Upper East Side.

The lead Valerie Solanas pumped into Warhol (for which she served only three years) is only one violent scene among many that punctuate this book. It wasn’t just Freddie Herko or Solanas or the drugs (pot, LSD, amphetamines) or the crystal meth Lance Loud later confessed he’d been shooting every day for twenty years, or Koutoukas’ slitting his wrists onstage. When Joe Cino’s boyfriend, an electrician, was electrocuted on a job in New Jersey in 1967, Cino, convinced it was suicide and not an accident, stabbed himself to death in his coffeehouse, then called a friend while he was dying. The friend was asleep but his roommate went to the Caffe and found “Joe on the floor surrounded by blood, lit only by the dawn sunlight and the Caffe’s twinkling Christmas lights.” (Stage that.) “After Joe killed himself,” said Robert Patrick, “both Harry Koutoukas and Ondine came to me in tears saying that they had killed Joe by slipping him some drugs. They had gotten some terrifically good, superior acid, and each of them had dropped a tablet of it in his drink. They never knew the other had, by the way. Each of them thought they had killed Joe.” After Joe’s death the whole scene shifted to the East Village.

McLeod devotes more than one chapter to the video artist Shirley Clarke (whose 1967 documentary Portrait of Jason starred a gay black hustler), but his main subjects as we move from the ’60s playwrights and The Factory are the career of Lance Loud and the rise of punk rock. An American Family debuted on public television in 1973. Lance was the first openly gay man on TV. “Television ate my family,” Lance would say before he died at fifty of Hepatitis C and HIV. But before that happened, he and his mother Pat moved to New York, where he finally got to meet the idol to whom he’d written letters when still a teen in Santa Barbara: Andy Warhol, the man behind the Velvet Underground. When Lance went out at night, it was to Max’s Kansas City, not the Eagle’s Nest, and although his band the Mumps never got a record contract, it was the punk scene to which he aspired. The punk scene arose in the early ’80s, when I began to see around the East Village the words “clones go home” stenciled on the sidewalk by a group called Fags Against Facial Hair, a new generation wanting to shove its predecessor aside. But reading McLeod, one learns that Blondie was on the scene in 1975—the midpoint of disco, or rather what disco was before Saturday Night Fever mass-marketed it.

“Disco,” according to Clem Burke, the drummer for Blon-die, “was probably more subversive than punk rock. That whole lifestyle—the underground clubs, the gay culture, the leather scene.” But rock critics of the time either ignored or despised it. The Age of Clones, which The Downtown Pop Underground doesn’t discuss, was different from punk in both origin and spirit. Disco came out of R&B, while punk was a commentary on white rock. Clone culture was different in other ways as well. It lacked the cynicism that the Factory, and punk rock, either believed in or adopted as an attitude. Its ideal was the Marlboro Man, not Sid Vicious. Its play was The Boys in the Band, not The Madness of Lady Bright. Clone culture had its drag queens, but they weren’t Jackie Curtis, Holly Woodlawn, or Candy Darling; they were anyone who put on makeup for the Gay Pride Parade.

The Saint, the climax of the gay New York discotheque, was located in the same building on Second Avenue that had previously housed the Fillmore East, Bill Graham’s short-lived attempt to introduce the San Francisco rock venue of the 1960s to New York. But the ’60s and ’70s, the hippies and drag queens, the punk rockers and the clones, all seem to have existed independently of one another. Still, even if these various milieux ignored or disdained one another, they were all variations on the same elements: homosexuality, invisibility, and energy bubbling up from people who had been excluded from the mainstream.

That the Stonewall rebellion is barely mentioned in what is after all a history of the arts is understandable, but that night seems to have been part of the general ferment of the downtown subculture that McLeod admires. It was an event in which the angry drag queen was central, but when it finally happened, it wasn’t a drag queen who was the first to come out of the bar and into the paddy wagon, according to Jim Fouratt, who was walking home that night from a nightcap at Max’s Kansas City; it was a bull dyke who rocked the vehicle back and forth until the door popped open, while other people began doing what the police had never seen gay people do before: throw things at them.

That energy seems to have faded now—along with the force of drag queens. True, there’s Kiki and Herb, but where’s Jackie Curtis, or Divine in a crab outfit singing “A Crab on Your Anus Means You Are Loved” in Journey to the Center of Uranus? After the ’70s, drag turned into Wigstock and the Halloween parade in New York, then into the queens in Provincetown that straight families came to gawk at, and finally into RuPaul’s TV show. It’s totally harmless now—something the playwrights on Cornelia Street were anything but. When someone asked Jackie Curtis to do something camp, he shouted, “Camp? I’ll give you camp! Concentration Camp!”

There is in McLeod’s history—which is made up necessarily of interviews and paraphrased memoirs—the occasional feeling that you had to be there to have appreciated what went on. Like Balanchine’s ballets, these drag performances were in the end ephemeral. All we have are books like the one McLeod, happily, has put together. Otherwise, it’s gone. It’s dwindled to RuPaul’s Drag Race—the final Disneyfication. Drag queens are now being invited to branches of our public libraries to read stories during the Children’s Hour. But I can’t imagine them reading the lyrics to “He’s Got the Biggest Balls in Town,” one of the songs Jackie Curtis wrote for a show called Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit:

He’s got the biggest balls in town, even upside-down

You ain’t seen balls till you’ve seen Paul’s:

Round, firm, and meaty. You could write a treaty on those

balls!

He’s got guts in those nuts! When Gabriel calls they’ll blow his

balls.

Too much for kids in a public library, no doubt, but, when you think about it, it was out of this erotic craziness that Stonewall burst forth … which, of course, would lead to drag queens reading stories to kids in public libraries.

Andrew Holleran’s fiction includes Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.