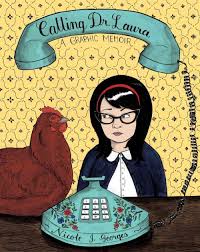

Calling Dr. Laura

Calling Dr. Laura

by Nicole J. Georges

Mariner Books. 288 pages, $16.95

THE TERM “comic book” might conjure dime-store entertainment, tales of superhumans in capes and tights. But take a look at the alternative comics scene, and GLBT memoirs full of candor and insight abound. From Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006) on her relationship with her closeted gay father to Ellen Forney’s Marbles (2012) on her bisexuality and bipolar disorder, one sees gay and lesbian stories blossom in this marriage of the well-drawn illustration and the apt turn of phrase. Comics are at once art and literature, and the best memoirs combine the narrative power of both.

She confers with her sister Liz, who confirms that their father is alive. In the meantime, Nicole’s sister comes out to her mother as bisexual, who says, “No daughter of mine is going to be a dyke.” Because of her mother’s scorn, Nicole cannot come out to her mom either about being a lesbian or about her biological father: “For years I had ‘friends’ instead of dates. Boyfriends turned into ‘roommates.’” Nicole’s live-in girlfriend Radar grows weary of being kept a secret from Nicole’s mother. As the narrator’s denial grows greater, Radar becomes more remote. With the help of her sister Liz, Radar, and, yes, Dr. Laura Schlessinger—“So I’m a radical feminist taking in a little right-wing conservative radio. What gives?”—Nicole must overcome her inertia for a chance at a healthy relationship with her mother, her girlfriend, and herself.

It’s easy to get caught up in the whimsy of Georges’s stylish illustrations. The author draws herself smartly clad in cat’s-eye glasses against precious backdrops: in her room playing board games, in the company of her pet chicken, onstage performing with her girlfriend’s indie rock band. On the surface, her references summon the cheeky and hip TV show Portlandia. But within this cute comic bildungsroman are, as in the work of Bechdel, weighty themes of self-acceptance and creating alternative families.

Throughout Georges’s memoir, her family is a source of danger. She says of her stepfather, “I can’t recall there ever being peaceful middle-ground in Florida, only conflict.” The trauma results in young Nicole’s encopresis, or uncontrollable bowel movements. Upon her mother’s divorce from her stepfather when Nicole is in grade school, the author says: “I was glad when my mother finally broke it off with Ed, what with all the fighting, the choking, and obvious terror.” In this environment, Nicole crafts a family out of her stuffed animals. Later, she embraces her pets as substitute relatives. She comforts her wounded chicken as a way of comforting herself: “I will heal you.” When she moves in with Radar, she rejoices that they have “four new dogs in one new house.” As Nicole’s sister Liz says, “The Georges are not your family. We have to build our own families.” In the narrator’s case, her makeshift family is an anthropomorphic one.

Nicole transmutes her affection, finding love with Radar, with her sister Liz, and eventually with her mother. Ultimately, she does confront her mom, coming out to her and asking about her biological father. And while the answer she finds can’t make up for the years of witnessing abuse or hiding her lesbian identity, she discovers a sort of comfort with her new half-siblings whom she welcomes to the fold. In the process, she has shepherded the reader into her fragile, sweet narrative so that we may be a part of her revelatory journey too.

________________________________________________________

Grace Bello is a lifestyle and culture writer based in New York City.