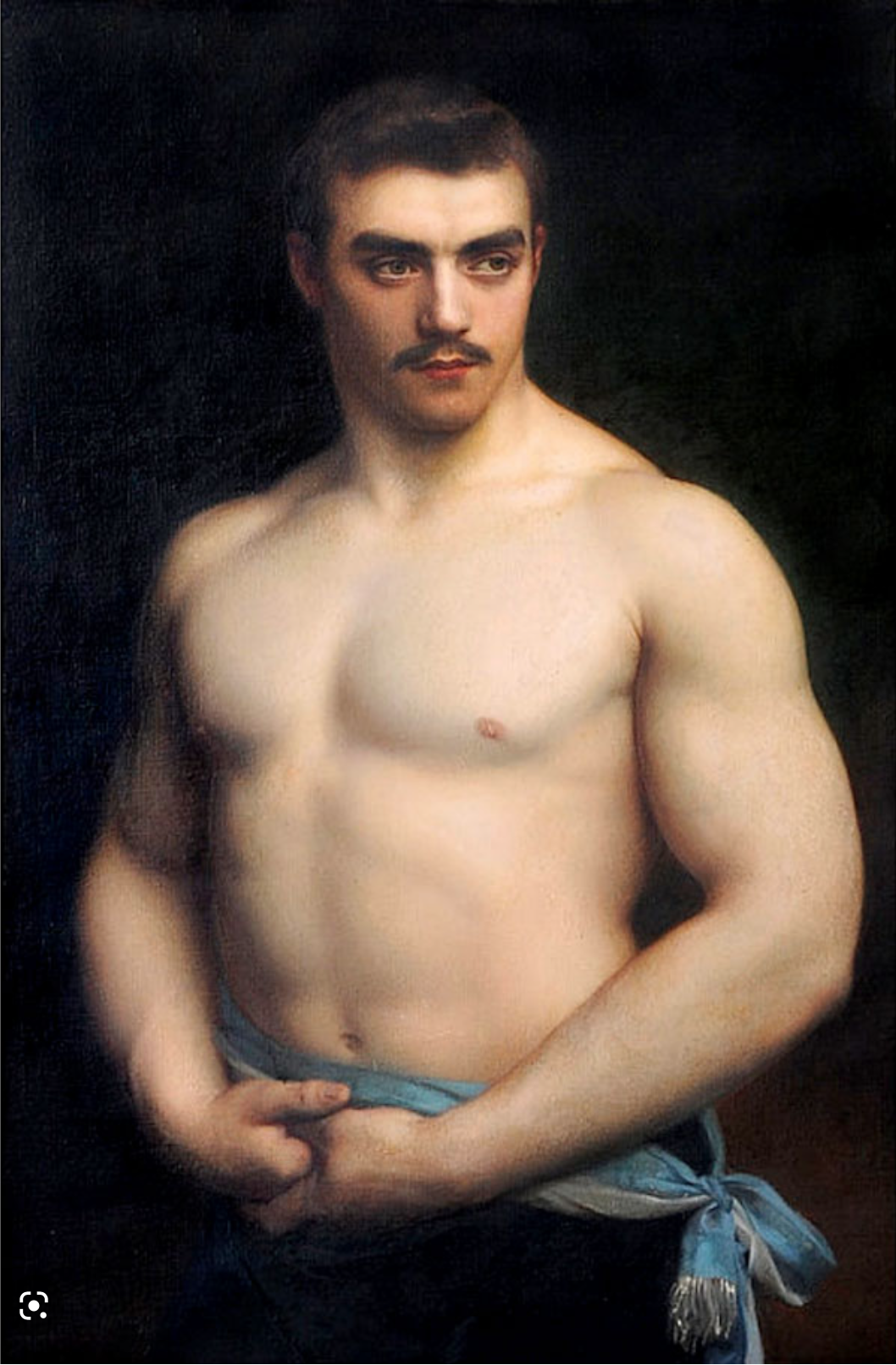

A PORTRAIT of strongman and wrestler Maurice Deriaz (1885–1974) executed by Gustave Courtois (1852–1923) in 1907 has not been forgotten. It currently makes the rounds on social media sites dedicated to the male figure or to artistic images of masculine bodies. But regardless of the medium, the portrait seduces the viewer through its beautiful depiction of Deriaz’ manly physique and its palpable eroticism.

In this half-length portrait, Deriaz stands slightly turned to the right. The flawless porcelain-white skin of the brawny exposed chest stands out against the dark, blurred background. A light blue sash with a silver lining hugs the waist below the navel, tied in a knot on Deriaz’ left hip. The light shines brightest on the middle of the hairless chest and the left clavicle, creating shadows on the right side of the body. The gracefully flexed arms allow the biceps to bulge slightly as the left hand gently clasps the right hand below the sash. Lush brown hair crowns the proud face while the curvatures of the bushy eyebrows—echoed by the discrete moustache over thin carmine lips—frame the seductive gaze from eyes looking intensely towards the left, avoiding direct contact with the viewer.

For a portrait artist of Gustave Courtois’ caliber, the work signaled a bold statement. A bare-chested wrestler and bodybuilder was out of place in the polite society usually associated with academic art at the time. When shown at the Paris Salon of 1907, it raised many eyebrows among critics. One journalist accused Courtois of bad taste for showing the athlete bare-chested, while another speculated on the artist’s experience of pleasure while executing the work: “What intense pleasure M. Gustave Courtois must have felt while giving shape to the triumphant torso of the athlete Maurice de Riaz! How he has caressed its sinuous contours!” Without a doubt, the critics’ uneasiness upon seeing the portrait lay bare the homoerotic content of the piece and hinted at Courtois’ “deviant” sexuality, raising suspicions about the relationship between the artist and model. But who were Courtois and Deriaz, and what was the nature of their relationship?

We don’t know if Deriaz actually did more than just “stand still” for Courtois, but the portrait establishes a connection between “deviant” sexualities and the bodybuilding craze that ran from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th and beyond. After the Oscar Wilde trial had set off a “queer panic,” the more suspect ephebic and feminized representations of the male body were replaced by muscular, virile strongmen who embodied national ideals of manhood. At the same time, such representations served as screens behind which a homosexual audience could remain closeted while enjoying the sight of ideal masculine bodies referencing classical antiquity.

Maurice Deriaz had actually graced the September 15, 1906, cover of La Culture Physique, a very popular culturist magazine published in France from 1904 to 1967 (with notable hiatuses due to world events). When compared to Courtois’ work of 1907, there are striking resemblances between the photo and the treatment of the body in the painting. The shadow on the right, the bulging vein on the right forearm, the right clavicle all mirror each other, giving the portrait its photographic quality. In this way, Courtois violates several unspoken rules of academic portraiture. Whereas most athletes featured in artworks were presented either in the midst of performing an athletic feat or as a mythological hero, he chose to humanize Deriaz by giving him a name and a face that would be recognizable to those acquainted with the wrestling world and La Culture Physique magazine. Rather than focusing on sartorial details—a long staple of portraiture to define the sitter’s psychology—Courtois presents Deriaz half naked. The lack of any other props (aside from the sash) to contextualize the subject further emphasizes the corporality of Deriaz as a real person. Furthermore, by alluding to the cover of La Culture Physique, the portrait functions as a winking reference to the numerous photographs by both famous athletes and private individuals published in the pages of the magazine.

In fact, every issue was peppered with illustrations of what we could call “selfies” of half-naked (and sometimes fully naked) men, including those of professional and amateur athletes. These photographs were at times combined into collages and presented as part of bodybuilding competitions for amateur readers, accompanied by vital statistics of the contestants. From our vantage point, these collages eerily resemble modern-day dating apps—Grindr avant la lettre—with body pics and stats. A young Maurice G. from Franconville, for instance, submitted his picture along with a letter, published in the November 1904 issue, in which he detailed his “stats,” including his height, weight, waist size, and age. For other readers living in his area, it wouldn’t have been difficult to recognize Maurice G. as the subject featured in the magazine. These “selfies,” in turn, mirrored Courtois’ portrait, establishing a wider unspoken network of those “in the know” who were connected through the figure of Maurice Deriaz as displayed in the pages of La Culture Physique.

Courtois’ portrait also references the “classicizing” mania brought about by the physical culture fad. By that I mean the quoting of classical sculptures to justify the new masculine values associated with national virility as inscribed in a muscular body. Athletes posing in the magazine usually recreated the poses of famous statues and incarnated mythological heroes. In the portrait, Courtois lightens Deriaz’ skin and completely removes the chest hair that’s visible in photographs of the wrestler, thereby transforming him into a statue. This cosmetic tactic was often used by models at the time, going as far as to remove hair from armpits, chests, and pubic areas, or even the whole body, as well as oiling the skin. The classical veneer allowed the models to appear to embody æsthetic ideals rather than erotic intentions, yet the possibility of the latter was always at the viewer’s discretion.

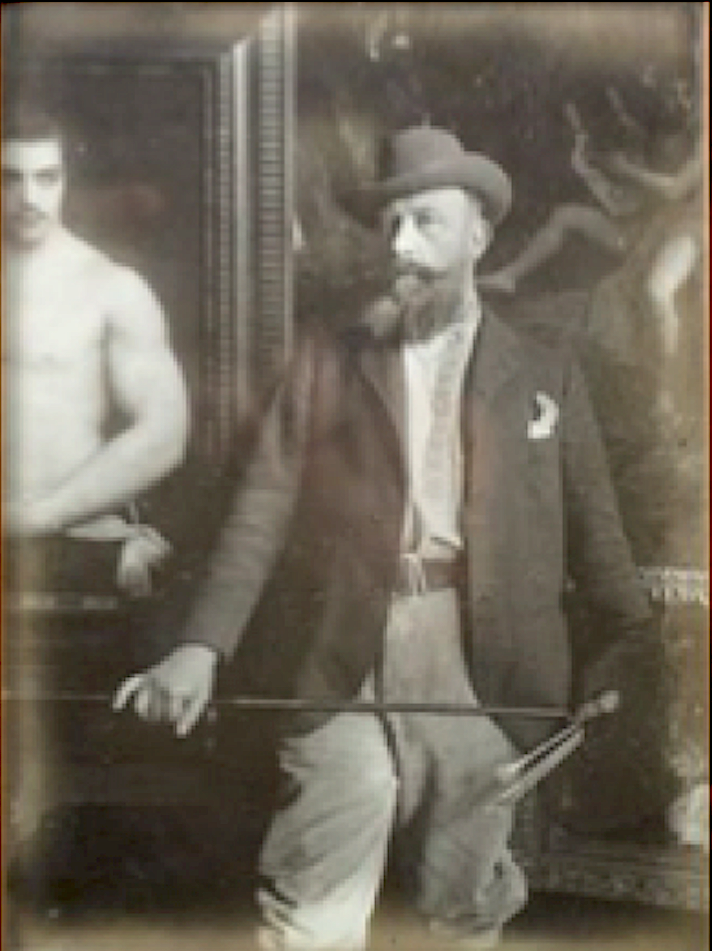

It remains difficult to deetermine whether the relationship between Courtois and Deriaz remained strictly professional. A recently discovered 1910 photograph of Courtois standing next to Deriaz’ portrait is dedicated to the strongman in the following way: “To Maurice de Riaz, a souvenir of his painter and friend, Gustave Courtois.” It is telling that the artist chose to call him “friend” and to stage a photograph with erotic undercurrents. The pose of the artist is suggestive of sexual prowess, the phallic maulstick pressed firmly against the pelvic girdle, creating a bulge in the front of the pants and directing the gaze of the recipient of the photograph—in this instance, Deriaz—toward the crotch. Furthermore, Courtois deliberately chooses to stand between the portrait of Maurice on his right and a lost work of 1904 representing Apollo playing the lyre on his left. As we know, Apollo’s exploits include many forays into same-sex love. Hidden from view by Courtois’ body is an image of a young boy playing the flute, perhaps an allusion to Cyparissus, the beloved of Apollo. Given the 33-year age difference between Courtois and Deriaz and the positioning of the paintings, the “unspeakable” vice of the Greeks inhabits the staging of the photograph.

Whatever the nature of their relationship, the 1907 portrait of Maurice Deriaz certainly raises questions about the representation of the male figure in art and its homoerotic—if not outright homosexual—potential when placed in the context of the physical culture fad of the period and Courtois’ known proclivities toward men. Courtois offers the viewer—who was assumed to be male in the times—a delectable portrait to be consumed either for its æsthetic or erotic content, recognizably similar to the images in La Culture Physique magazine. It is precisely its ambiguity in this respect that could produce a state of “homosexual panic” like the one experienced by the art critics quoted at the top of this article. By redefining and repackaging the image of Maurice Deriaz, Courtois transgressed the accepted boundaries between licit and illicit forms of visual pleasure and sexuality. It’s high time that we rediscover the works of this forgotten painter and re-evaluate his output within the context of masculinity and queer studies. In the meantime, we can continue to appreciate the immortalized beauty of Maurice Deriaz captured in this stunning portrait by Gustave Courtois both as an æsthetic object and a seductive work of art.

Eduardo A. Febles is Professor of French and Francophone Studies at Simmons University in Boston.

Discussion1 Comment

Fascinating article. I’d love to read Professor Febles’ take on two other 19th-century French artists of special queer interest, Antoine Chintreuil (one of the original Parisian Bohemians, who had a lifelong, much younger companion) and Gustave Boulanger (whose Hercules of 1861 is still a jaw-dropper, and who had a very curious personal life).