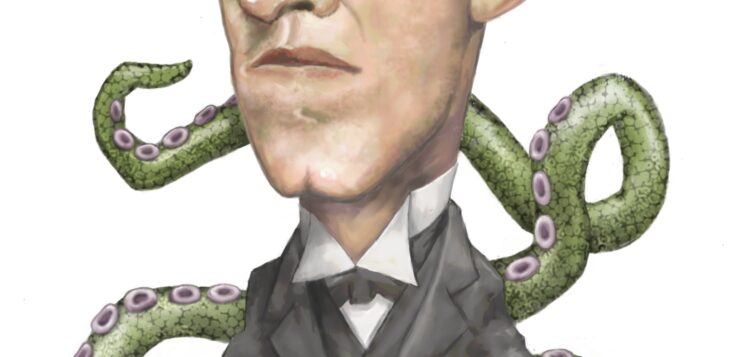

THE HORROR FICTION of H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937) is best known for its tentacled monsters, demented occultists, and adjective-heavy phrases like “dissonances of exquisite morbidity and cacodaemoniacal ghastliness.” Lovecraft’s work appeared primarily in cheap pulp magazines like Weird Tales, and while he died penniless, he is now considered one of the world’s great horror writers. Toys, games, and movies based on his stories continue to pour out of the dream factories, and his writing has been the subject of academic conferences, philosophical treatises, and essays by Joyce Carol Oates.

Despite all the recent attention, few critics have examined the homoerotic presence that pervades many of Lovecraft’s stories. Female characters are rare, and his male characters inhabit a homosocial world filled with same sex-pairings and attractions. Sailors, lonely academics, and sorcerers—all of whom can be read as gay—lurk on the outskirts of civilization, learning horrific secrets and threatening the social order.

Ambiguously gay male duos appear frequently. The unnamed male narrator of 1921’s “Herbert West—Reanimator” spends seventeen years as the companion and assistant to the story’s titular physician. The two bachelors live together in isolated houses where they experiment with reanimating corpses. West is described as “blonde, clean-shaven, soft-voiced and spectacled,” but the men he raises from the dead are more butch. His first subject is a “brawny young workman,” and most of the others are similarly brawny. The narrator writes, perhaps jealously, of how West stares at men with healthy physiques on the street. It’s all in the name of science, right? West is ultimately dismembered by a horde of his undead subjects, led by one whose reconstructed face is “handsome to the point of radiant beauty.”

A similar male couple appears in 1924’s “The Hound.” This time the duo are debauched æsthetes who, bored with romance and adventure, turn to grave-robbing to get their kicks. Lovecraft suggestively describes their nocturnal thrills as the “stimuli of unnatural personal experiences” that require them to increase “the depth and diabolism of our penetrations.” Like Herbert West and his unnamed assistant, this decadent duo live alone on the fringes of society, where they can indulge their appetites undisturbed.

A similar male couple appears in 1924’s “The Hound.” This time the duo are debauched æsthetes who, bored with romance and adventure, turn to grave-robbing to get their kicks. Lovecraft suggestively describes their nocturnal thrills as the “stimuli of unnatural personal experiences” that require them to increase “the depth and diabolism of our penetrations.” Like Herbert West and his unnamed assistant, this decadent duo live alone on the fringes of society, where they can indulge their appetites undisturbed.

In the 1923 story “Hypnos,” an unmarried male sculptor finds his muse in a man who’s suffering from a convulsive fit in a train station. The man’s face is beautiful, his forehead is godlike, and he reminds the sculptor of an ancient Greek faun brought to life. “I knew thenceforth he would be my only friend,” the sculptor says as he brings the man home to live with him. He compulsively sculpts his handsome new friend before the two turn to “impious exploration” of astral realms (with dire results).

Lovecraft dedicated “Hypnos” to his close friend Samuel Loveman, a gay poet and bookseller. Loveman was only one of several gay men in Lovecraft’s circle, the other most notable being one Robert Barlow, who was chosen by Lovecraft to be his literary executor. Lovecraft was 44 years old when they met; Barlow was only sixteen. Lovecraft made several visits to Barlow’s family home in Florida, where the two were inseparable and spent much time rowing and talking alone in an isolated cabin. A fictionalized—and explicitly gay—account of their relationship is the centerpiece of Paul LaFarge’s 2017 novel The Night Ocean.

Despite these hints, there is no firm evidence that Lovecraft was gay in our sense of the term. His only known romantic and sexual partner was Sonia Greene, an older woman whom he married in 1924. Their marriage lasted only two years. Greene later told friends that she always had to initiate sex with Lovecraft. “Howard was entirely adequate sexually, but he always approached sex as if he did not quite like it,” she told the writer August Derleth. This could be taken as evidence of repressed homosexual tendencies or, as biographer S. T. Joshi suggests, evidence that Lovecraft was borderline asexual. Then, too, given that his father died from syphilis in a Providence sanitarium, it’s possible that Lovecraft had a deep fear of sex. His mother later died in the same sanitarium from unknown causes. In light of his family history, it’s not surprising that the heterosexual couplings in his stories are usually fraught with peril and even terror, whether the issue is incest, bestiality, ritualized sex with demonic entities, or rape by aquatic monsters. Regardless of its psychological source, homoerotic situations both subtle and overt appear repeatedly in many Lovecraft stories. In “The Electric Executioner” (1930), a collaboration written with Adolphe de Castro, a frail young man who is about to be married finds himself trapped on a train with a crazed occultist named Arthur Feldon. Feldon, who is tall, handsome, and very strong, easily overpowers the young man. As he prepares to murder him, Feldon chants the names of youthful Greek demi-gods, including several (Hylas, Atys, and Dionysos) who had older male lovers. The occultist is a symbolic threat to heterosexual marriage that must be defeated before the wedding can occur. The young man eventually outwits Feldon and kills him. The story concludes with the young man marrying his bride. But marriage isn’t safe, as Lovecraft shows in “The Thing on The Doorstep” (1937). After the wealthy and scholarly Edward Derby marries a young woman, he learns that her body is possessed by the soul of her deceased father, a sinister wizard, and that the father-in-law wants to take over Derby’s body next. Body-swapping, gender reversals, and murder ensue. Another marriage dissolves less gruesomely in “The Strange High House in The Mist” (1931) when a bored college professor and his family vacation in a seaside town. The professor visits an old house that the locals shun, but instead of finding terror inside he is greeted by a handsome, bearded sailor dressed in antique clothes. The gentle-voiced sailor shows him sea-gods and other wonders all night long, and the next morning only the professor’s physical body returns to his family. His soul remains in the old house with the sailor, and their laughter echoes over the town. As the story ends, the locals grow concerned that the town’s young men will lose their fear of the old house and join the mariner and professor there. In Lovecraft’s world, the gays really do recruit. Sailors also figure prominently in one of Lovecraft’s most famous tales, “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928), which tells how an elderly bachelor professor learns that a monstrous extraterrestrial deity lies dormant under the Pacific Ocean. The tentacled god, unpronounceably named Cthulhu, first announces his presence to the modern world by afflicting artists and other sensitive types with nightmares. The professor meets one of these artists, a languid sculptor who socializes only with other “aesthetes”: “He called himself ‘psychically hypersensitive,’ but the staid folk of the ancient commercial city dismissed him as merely ‘queer.’” Lovecraft uses “queer” nine times in “Call of Cthulhu” to describe everything from alleyways to pieces of art. Presumably it means “unusual” when describing an alleyway, but its definition is undoubtedly more ambiguous when applied to the fey sculptor. Lovecraft also describes a group of ethnically diverse sailors as “queer and evil-looking.” Sailors, the elderly professor discovers, are Cthulhu’s main worshippers. And they are unambivalently queer in the modern sense of the word, as the police discover when they raid a ritual held in a swamp. As they approach the site of the ritual, the police hear a mad “cacophony of the orgy” and “howls and squawking ecstasies.” Upon reaching the bacchanal, they are horrified by what they see: “Void of clothing, this hybrid spawn were braying, bellowing, and writhing about a monstrous ring-shaped bonfire.” It can only be described as a ritualized naked sailor orgy. The critic Edmund Wilson once wrote in The New Yorker that “Lovecraft was not a good writer. … The only real horror in these fictions is the horror of bad art and bad taste.” Despite earning critical disdain after his death, Lovecraft’s tales continue to inspire artists and fans eighty years later. He is now a major force in popular culture and attracts attention from big-name artists. Stephen King has said that “H. P. Lovecraft has yet to be surpassed as the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.” Oscar-winning filmmaker Guillermo del Toro is also a Lovecraft fan and incorporates Lovecraftian imagery and themes into his films. This winter Nicolas Cage starred in Color Out of Space, a film based on the story of the same name, while this summer HBO will release Lovecraft Country, a show based on Matt Ruff’s 2016 novel exploring racist themes found in Lovecraft’s work. Jordan Peele, who won an Academy Award for Get Out, is one of the producers. Most film adaptations and other Lovecraft-inspired pop culture ignore the source material’s homoeroticism. One exception was 1985’s Re-Animator, a gorily comedic film based on “Herbert West—Reanimator.” Although Re-Animator turns the story’s unnamed and devoted narrator into a robust heterosexual male named Dan Cain and adds lots of female nudity, Herbert West remains soft-spoken, bespectacled, and undeniably fey. Played by Jeffrey Combs, West intrudes into Dan’s life and disrupts his relationship with a pretty female medical student. Does he just need Dan’s help to resurrect the dead, or does he want something more? Re-Animator accurately captures the queer ambiguity lurking in so many of Lovecraft’s tales. But most Lovecraft films avoid the queer aspects of the original stories or add heterosexual elements not found in them. For example, a 2005 film version of “Call of Cthulhu” added female celebrants to the orgy scene, as have comic book adaptations of the story. It’s not surprising. Given the density of Lovecraft’s sometimes turgid prose, few readers even seem aware that the orgy features strictly man-on-man action. Perhaps the world is not yet ready for Cthulhu’s radical (and slightly sinister) gospel of queer sexual liberation; and Lovecraft’s own opinion on the matter remains unclear. Did he want to join those naked sailors in the swamp? Was he terrified of them? Or was it both? If the first sentence of “Call of Cthulhu” is any indication, he may not have known himself: “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.”

Peter Muise, who writes about New England folklore and legends, is the author ofLegends and Lore of the South Shore.

Discussion2 Comments

The explicitly curious thing about Lovecraft’s relationship to Barlow is that he elder left his considerable writing to a NINETEEN YEAR OLD he began corresponding with at the age of 13. It’s one thing to be a friend of someone, and quite another to hand over your legacy.

None of this, of course, is even possible under current day LGBTQ ideology, which no doubt ensures an ongoing silence, which “serious” i.e. straight critics are happy to oblige.

Lovecraft is quoted as describing pederasty as “disgusting”, ignoring the well known fact that (a) many homosexuals throughout history have vehemently publicly denounced homosexuality in order to cover up their own homosexuality, and that (b) many people of any number of sexual stripes are in denial about what it is they want–until they they do it.

Surely it’s possible a 40 something man would visit a teenager multiple times, alone in a cabin, for reasons other than sexuality, even if that teen later committed suicide because he was being outed as a homosexual. And surely it’s possible that Lovecraft was asexual. Possible and convenient.

You know where my thoughts lay.

All of this is pure invention on your part. There’s nothing in there that points to West and his assistent being homosexual and Lovecraft considered it a “sissy” thing.