The Homoerotics of Orientalism

The Homoerotics of Orientalism

by Joseph Allen Boone

Columbia University Press

520 pages, $50.

ONCE EVERY DECADE or so, a book appears that revolutionizes the field of GLBT studies. For many critics, Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality may have been that title in the 1970s. John Boswell’s Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality is surely the 1980s title. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble can lay claim to this achievement in the 1990s. In the intervening decades, however, there has been a sense of critics treading water—or at best extending rather than reassessing the tenets of structuralist and post-structuralist thinkers into marginally new contexts.

Across the same period, GLBT studies, while ongoing, have suffered perhaps from no longer being the new kid on the block. While the sub-discipline embedded itself in university departments starting in the ’90s, and sexuality theorists dutifully took their place on many sophomore syllabi, the publishing world was more fickle: academic presses soon found new areas of niche interest, such as animal studies, while mainstream publishing almost entirely forgot that it had once been interested in gay and lesbian ideas (with rare exceptions, such as 2008’s The Greeks and Greek Love, by James Davidson).

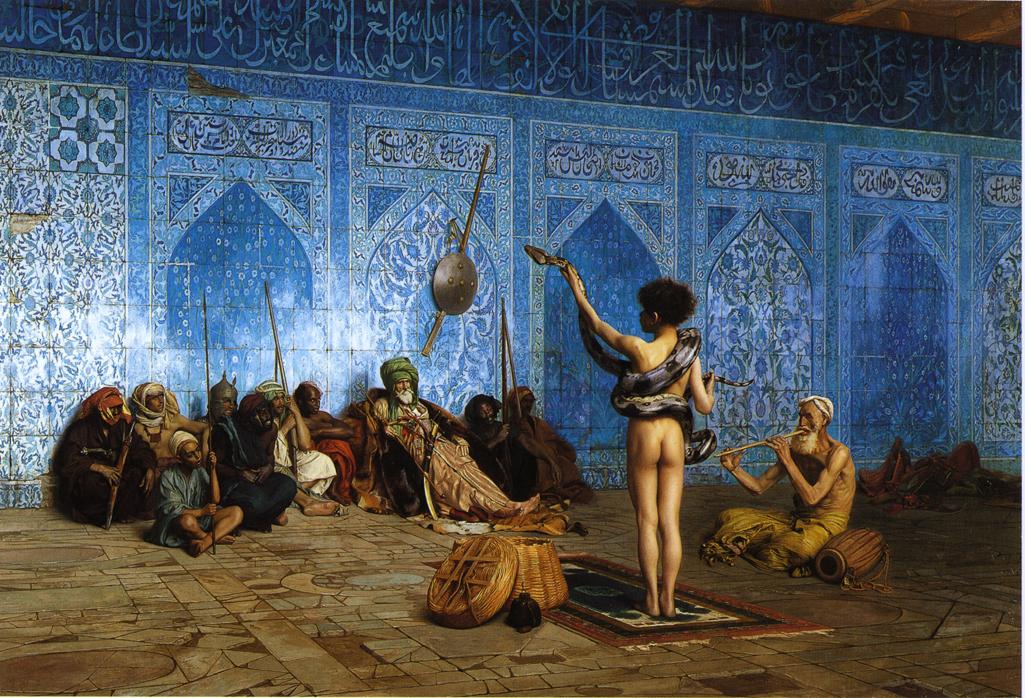

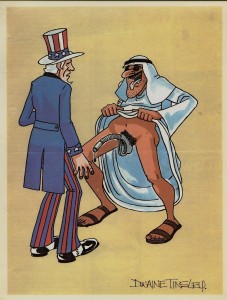

Now, Columbia University Press has transformed this narrative with a singular publication. For Joseph Allen Boone’s The Homoerotics of Orientalism is a book that upends current postcolonial thinking by presenting a massive, inchoate body of texts—literary and otherwise—mutually informing, supporting, and cross-referencing one another across the famously impervious East-West divide. (“East-West” here denotes relations between Western and Islamic cultures, following the formulation of Edward Said’s groundbreaking if flawed 1978 study, Orientalism.) By showing the ubiquity of male same-sex desires, cadences, and expressions within East-West discourses, Boone challenges the social constructionist dogma of feminists and queer theorists, who insist that such desires, cadences, and expressions are particular to a given cultural nexus.

Boone finally makes sense of the flow of writings, paintings, films, and other forms of art between the Islamic East and the Christian West, and what emerges is something far more credible than Edward Said’s original thesis, which was, to summarize, that Western travelers dabbled in the East, objectified it, “sold” it back to a Western clientele, and denied the subjectivity of the ethnic, religious, and cultural “other.” Said’s Orientalism set out to expose and document a persistent Western tendency both to romanticize and to patronize Arab and Middle Eastern culture. But Boone lays to rest utterly the notion that a straightforward, dogmatic, and monolithic power relationship was always being played out when Western writers and artists headed to the Near (or Middle) East.