IN THE LAST TWO DECADES, Western European nations have enjoyed mostly steady progress toward the acceptance of homosexuality. For their Eastern European counterparts, however, negative attitudes and intolerance toward homosexuality and homosexual people, or homonegativity,* continue to be remarkably prevalent, with some nations experiencing stagnation or even regression in acceptance in recent years. Gay rights movements have been met with repression and harsh cultural resistance. We can see this particularly in the recent violence toward LGBT persons in Chechnya, an overall rise in hate crimes across the region, and even increases in legal measures to discriminate against this minority.

In general, Western nations have done little to address the rise in the persecution of LGBT persons in Eastern Europe, though the media occasionally offer glimpses of the problem when tensions flare. For example, the West expressed disapproval when the Russian parliament passed a bill criminalizing the “promotion of non-traditional sexuality” to minors, just before the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. Global attention to the issue quickly died down, and protests achieved little. Now, in the Chechen Republic, police forces have detained and brutally tortured over a hundred men in a violent anti-gay campaign. Many have fled their homes and even the country in an attempt to escape the purge. Though Russia has pledged to investigate these offenses, President Vladimir Putin continues to deny that homosexuals face any persecution in Russia at all. Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, responded in an interview by denying the ongoing violence, arguing that “there are no gay men in Chechnya … you can’t detain and repress people who simply don’t exist in the republic” (quoted in The Guardian, May 26, 2017).

Tracking Homonegativity

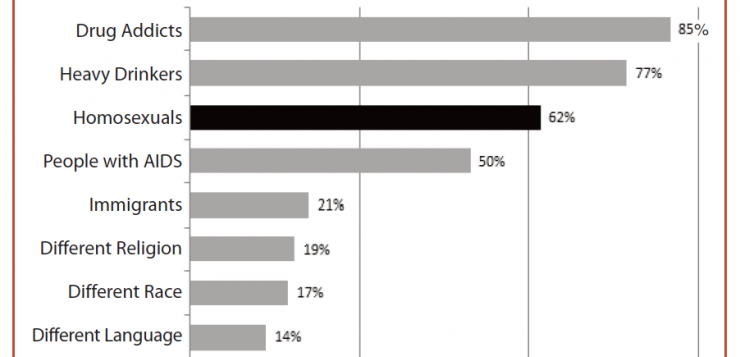

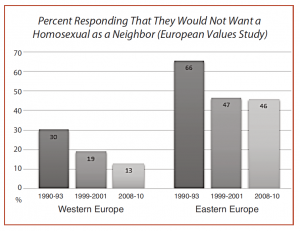

Public opinion surveys, and fluctuations of opinion over time, can provide crucial insights on this issue. For decades now, the European and World Values surveys have been asking respondents about their tolerance toward various groups. The divergence between patterns over time in Western and Eastern European nations has been striking. Below we present data for countries in the European Values Study (EVS) from 1990-2010. Among Western nations (i.e., Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Great Britain, and Northern Ireland), intolerance toward homosexual neighbors has dropped from an average of thirty percent to thirteen percent. In the East (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia), initial large drops in homonegativity between the early and late ’90s stagnated. As of 2010, average intolerance for homosexual neighbors was as high as it had been in the previous decade, and much higher than it ever was in the Western sample.

As we discuss further below, national averages vary, but in the most recent time period of this EVS survey, only one Western nation (Portugal, at 27 percent) had greater homonegativity than an Eastern European nation (the Czech Republic, at 23 percent). Further, it is important to note that even in 2010, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Estonia saw increases in the percent of people mentioning homosexuals as undesirable neighbors from the previous time period. As these older patterns make clear, the rising homonegativity and anti-homosexual violence we see occurring now has much deeper roots. To understand where more current opinion stands in Eastern Europe and post-communist nations, we focus on a subsample of six countries with data across thirty years from the World Values Survey. These patterns highlight the diversity of opinion change in these nations, but also the much greater, sustained homonegativity in each country as compared to the Western European trend.

Catherine Bolzendahl, an associate professor of sociology at UC-Irvine, has published articles in the European Sociological Review, The British Journal of Sociology, Gender & Society, and Social Politics.

Ksenia Gracheva is pursuing a doctorate at the School of Law at UC-Irvine.

This article was adapted from a piece published on-line in Europe Now Journal (www.europenowjournal.org), July 6, 2017, published by the Council for European Studies at Columbia University.