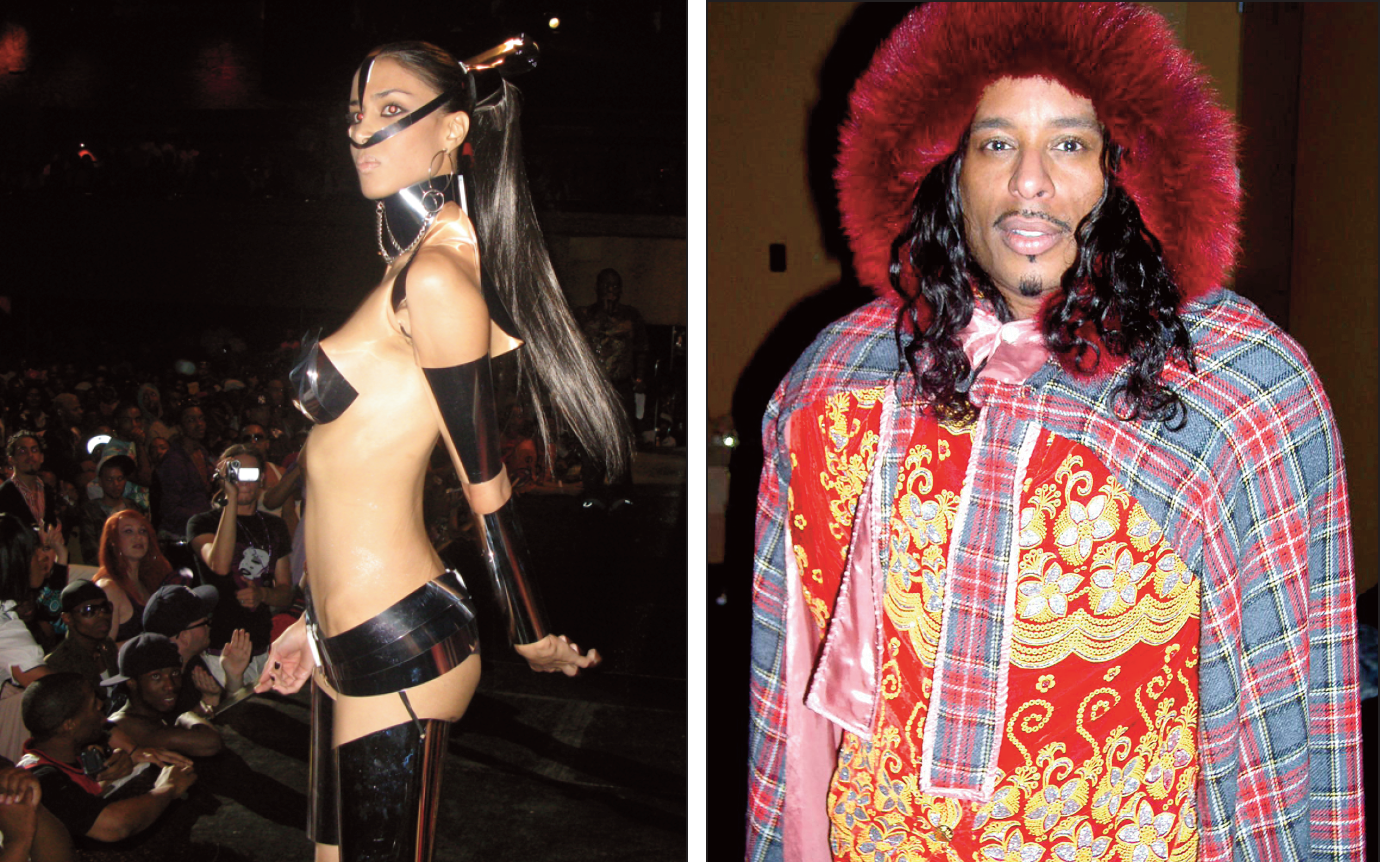

COMPOSED PRIMARILY of African-American and Latino people, many or most of them transgendered, the House and Ball community is a system of “houses” that participate in competitive drag balls. Centered in New York City, the houses have names like Xtravaganza, Ninja, LaBeija, the Garavani, and so on, and are organized as “drag families” headed by a “house mother.” It’s a community that’s as amorphous, inclusive, and diverse as any other GLBT (or lgbtq, etc.) universe. Like other subcultures within the larger subculture of “gaydom,” House and Ball has made direct and indirect contributions to popular culture while simultaneously resisting hegemony and absorption through the use of codified language and organizational structure.

Discussion1 Comment

I Love the magazine and thankful you exist. I’ve been an LGBTQIA activist since the late 60’s and yet there are so many stories and articles and aspects of our community I learn about each time I receive a copy of GL&R. I come from a print generation and value holding the magazine while I read. Thanks again Lee Zevy