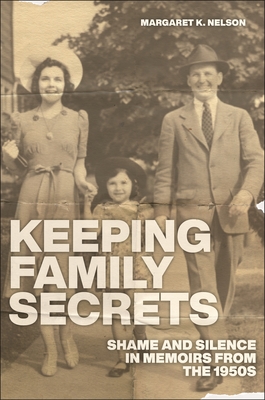

KEEPING FAMILY SECRETS

KEEPING FAMILY SECRETS

Shame and Silence in Memoirs from the 1950s

by Margaret K. Nelson

NYU Press. 256 pages, $30.

IN HER INTRODUCTION to Keeping Family Secrets, Margaret K. Nelson defines “family secrets” as “information that family members seek to conceal from each other or from outsiders because to do otherwise would risk eliciting not only embarrassment or minor discomfort, but also profound shame and, on some occasions, material hardship or even danger.” This is deep stuff. Nelson distinguishes “family secrets” from a general tendency to sanitize one’s public image. Her focus is on a decade known for its obsession with secrets: the 1950s, the era of McCarthyism, witch hunts for Communists and homosexuals, and the triumph of the isolated nuclear family as the standard social unit that “became hegemonic among White people.”

Needless to say, the “secrets” analyzed in this book have already been revealed many times over, as memoirs from this era abound. This book is itself based on memoirs by people who lived through this era, people whose often jaw-dropping personal stories came to light once it was safe to reveal them in memoirs. The “secrets” are organized into categories: absent siblings, i.e., children who were institutionalized all their lives because of physical or mental disabilities; same-sex desire among boys; “unwed mothers”; parents who were members of the Communist Party; unorthodox conceptions (hidden adoptions); and hidden Jewish ancestry. This was the kind of information that existed behind closed doors but clashed with the popular image of respectable families.

In a chapter titled “The Sounds of Silence,” Nelson describes the concealment of same-sex desire among boys. In most cases, boys learned that revealing such desires would be dangerous, and when parents or siblings suspected that young Johnny was not “normal” (sports-loving, into girls, etc.), there was often an unspoken family pact either to exclude him, or to shield him from the hostile outside world. As Nelson points out, homosexuality was illegal in most states, was considered sinful by most religious denominations, and was defined as a psychiatric illness until 1973. Possible consequences of being “outed” were so terrifying that staying closeted for life usually seemed the only safe option.

Why did the author focus only on boys? Nelson says that her research into memoirs did not turn up many memoirs by women who reported same-sex desire in their youth: “Gendered notions about what is acceptable for women to say and do might account for some hesitation on the part of publishers to have made visible that version of female sexuality.” The few accounts from females the author found differed from those of males in several ways. First, girls with romantic feelings for other girls could usually hide them in close friendships. Second, “the girls came to recognize their own desires considerably later.” This “coming out” process for women was often associated with discovering feminism, whereas for the men of that era it didn’t have the same connection to a political commitment. The author doesn’t mention the possibility of transgender children or teenagers in the 1950s, though they must have existed.

There were numerous opportunities for girls to become social outcasts in that era. In “Paying the Price of Silence,” Nelson discusses unwanted pregnancy among unmarried girls, which logically followed from another secret: illicit heterosexual sex. If a shotgun wedding could not be arranged, the consequences for the young mother were brutal. She was usually sent to a “home for unwed mothers,” where she was eventually pressured to give her baby up for adoption. In some cases, the long-term separation of young mothers from their children led to quests by adults raised by adoptive parents to find their birth mothers, and vice versa.

A search for hidden origins led several of the memoirists to uncover a variety of secrets: not only birth mothers, but in some cases alternative families. It’s not really surprising that some families hid their Jewish “roots” during and immediately after World War II. However, the extent of the secret culture of Communist families (parallel to other “minority” cultures), complete with summer camps for their children, seems like an aspect of postwar American life that should be better known.

What this book reveals is fascinating, but the stories that still seem to be missing are even more so. The author’s source material was clearly limited, and, as she explains, family “secrets” of the 1950s were often kept secret until the deaths of all those who knew the truth. This study could be considered the tip of an iceberg.

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Canada.