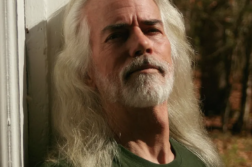

IN THE LATE 1960’s, America’s youth and thought leaders burst free from the confines of a staid conformist culture, demanding an end to the Vietnam War and racism, and, among a new generation of women, liberation and equality. But in the post-military draft and post-Watergate era and the height of disco-mania, former nun and lesbian political activist Virginia Apuzzo learned a very hard lesson: not all feminists are your sisters.

Having left the Bronx-based Sisters of Charity after Stonewall to fight for gay and lesbian rights, Apuzzo, a teacher at Brooklyn College with a master’s degree in urban education, found herself in 1976 arguing with leaders in the women’s movement over the inclusion of a gay rights plank in the Democratic National Committee Platform. She argued as a member of the Women’s Caucus of the National Gay Task Force, a caucus created in the home she shared with her lover Betty Powell, the first black lesbian on the Task Force’s board. The National Organization for Women listed the gay rights plank as one of their four demands—but they dropped it when lobbying failed. As Apuzzo explains in her remarkable, long interview for the Sophia Smith Collection, Voice of Feminism Oral History Project at Smith College, she saw “first-hand the duplicity around the commitment to lesbian and gay rights.”

But the fight gave her insight into politics, and in the following year, the time of Harvey Milk and Anita Bryant, Apuzzo founded the Lambda Independent Democrats and, in 1978, she ran for an Assembly seat. The year after that, she became an administrator in the New York City Department of Health under Mayor Ed Koch. In 1980, Apuzzo went back to the DNC as an openly lesbian delegate and co-author of the first gay and lesbian civil rights plank of a major political party. By now, she was a well-connected activist and strategic thinker—but unlike most of the more left-leaning gay Democrats at the time, she supported President Jimmy Carter over his primary challenger, Senator Ted Kennedy.

It was at the New York City Health Department in 1981 that Apuzzo first became aware of the mysterious disease that was impacting gay men, called “GRID” at first for Gay-Related Immune Deficiency. In fact, it was Apuzzo, along with Bruce Voeller, who convinced the federal government to change the designation of the disease from GRID to AIDS. In 1982, she became executive director of the Task Force, replacing director Lucia Valeska after the latter told an insensitive AIDS joke at a Dallas conference and was forced to resign.

Apuzzo immediately shifted the Task Force’s focus to AIDS. Having created an infrastructure staffed with crisis-trained volunteers for an anti-violence project hotline, she was able to convert that structure into the first national AIDS hotline. Later, the federal government would approach the Task Force for help setting up its own AIDS hotline.

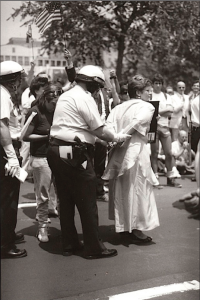

It was Apuzzo who first put AIDS into the context of a larger health issue related to racism, homelessness, and drug addiction. She became one of the most prominent spokespeople on AIDS, testifying at the first congressional hearing on the subject, where she wasn’t shy about criticizing the government for its laggard response, following up with a request for the extraordinary sum of $100 million to research and fight the disease. She continued to testify at congressional hearings about the burgeoning epidemic—as well as joining other activists in street protests.

In 1985, she went into government, serving for six years as deputy executive director of New York State’s Consumer Protection Board. From that perch, she challenged pharmaceutical companies over pricing and unsubstantiated claims for new hiv/aids drugs, forced funeral homes to bury the dead, and changed discriminatory policies in insurance coverage. Governor Cuomo also named her as Vice Chair of the New York State AIDS Advisory Council, where she served from 1985 to 1996.

On October 1, 1997, President Clinton appointed Apuzzo as Assistant to the President for Management and Administration, a move that made her the nation’s highest ranking openly gay or lesbian government official. Ten years earlier, she had been arrested outside the White House while protesting the Reagan Administration’s lack of response to the AIDS crisis. Under Clinton, and with help from her assistant Jeff Levy, Apuzzo secured Social Security disability for people with AIDS.

Apuzzo went back to the Task Force in 1999 as the first to hold the Virginia Apuzzo Chair for Leadership in Public Policy.

KO: Could you describe dealing with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services during the Reagan years and dealing with Republican conservatives?

GA: One big lesson I learned from the election of 1980 was that our community can never afford the luxury of needing to be enthusiastic about a candidate once our options are clear. Disappointment with Jimmy Carter was high, and many hopes were dashed when Ted Kennedy lost the nomination to Carter. Many, particularly those in our most politically organized communities, decided that we would not work for or support Carter in the race against Ronald Reagan. Indeed, many in California believed Reagan unelectable and reasoned that there was no need to get out and push for Carter. I worked hard for Carter, organizing our community in eight key states. When I think of how distinctly different Carter’s response would have been to the onslaught of HIV and AIDS, I am staggered at the thought of how different things might have been.

Health and Human Services was a big disappointment and a big surprise. Secretary Margaret Heckler, supposedly a “liberal” Massachusetts Republican, showed virtually no grasp of the potential scope of the public health crisis. However, an Oklahoma “conservative” Republican who was number two at HHS, Dr. Ed Brandt, slowly became aware of what the cost of inertia in his department would be. In the course of his tenure, he sent us internal documents that reflected his substantiation of the need for the $100 million dollars we had requested in our congressional testimony. He arranged meetings with top department heads in HHS, including a meeting with Dr. James Mason on Mason’s first day at the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention].

But my mantra was: “Not just access—responsiveness.” To that end, we managed to negotiate Social Security disability for persons with AIDS from Acting Commissioner Martha McSteen, who headed the Social Security Administration. That was a huge coup, considering that this was in the Reagan era.

KO: What were the politics like against this backdrop?

GA: The experience of working just to get a Congressional hearing was unbelievable. Without [Congressman] Henry Waxman (D–California) and his incredible staff, I doubt we would have gotten that far. I considered Pennsylvania Congressman Robert Walker the most contemptible of the Republicans present. It was the clearest evidence of blatant right-wing hostility toward our community that I had experienced on the Hill. And it was unabashed. He didn’t even entertain the rhetoric of concern so popular among some bigots. He considered AIDS our own fault, would not acknowledge the incredible voluntary effort that the community had pioneered, and generally reflected the popular attitude that, as long as this disease was confined to the gay community and IV drug users, they got what they deserved.

KO: What prompted you to leave the federal stage and take a job in the Cuomo administration in New York?

GA: When I left the National Gay Task Force in 1985 and joined the Cuomo administration in Consumer Protection, I realized that we could use the power of government to bring insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies to the table, and did so. We did the first statewide price survey of the earliest AZT drugs to illustrate the enormous price being extorted from persons with AIDS and the disparities in price around the state for the same drugs. We pressed for and secured legislation to guarantee patient confidentiality. And the list of issues demanding attention kept growing.

For me it was the most tragic time of my life. Since the mid 70’s I had been traveling around the country organizing in communities like Columbus, Ohio; Huntsville, Alabama; Miami, Florida; Oklahoma City; Kansas City, Missouri; Syracuse, New York—not the East Coast–West Coast route often taken by others. When AIDS hit, I recall being in Miami and asking a crowd of about 200 members of our community if they knew any person with AIDS. Two or three hands went up. I told them that unless there were radical changes with regard to safe sex and drug use, unless they began to organize and demand a response from government, in a year everyone in that room would know someone with AIDS. The prophecy proved tragically accurate.

And that was the case as I continued traveling throughout the country, each year seeing whole segments of the gay male activist community wiped out in city after city. All this in the context of homophobia and fear, with little in the way of federal or state funding going to education. I lost friends, my very dearest friends and comrades in every community across the country.

KO: Jumping to the Clinton era—there were such high hopes for Clinton, especially when he seemed to promise that his administration would try to bring new infections down to zero. What did you think of his efforts at health care reform, and what do you think of Obama’s efforts now?

GA: I share the belief of many of us that no administration has treated this largest public health crisis of our time as a crisis. Sixty million people have been infected worldwide; thirty million have died. What does it take to see into the future and know that the failure to act is deadly? Or to see that the failure of the pharmaceutical industry to find a vaccine and cure is in its economic self-interest? Or that the future of those profits seems assured when you consider that over forty percent of new infections last year were among those fifteen to 24 years old. Albert Camus contended [in the novel The Stranger]that people would have to be mad to submit passively to a plague. How much more insane is it to submit to indifference on the part of those who could change the course of this crisis?

KO: I’m wondering if you could add just a tad more about the significance of 1985—of that time period—your transition from the National Gay Task Force to government and the change in the national conversation because of Rock Hudson’s AIDS announcement and his death?

GA: There is much to be said about this period you ask about: the mid-1980’s and that transitional moment. I cannot give the question the time and review it deserves, so I’ll say only this, and it’s really a personal perspective. I don’t know how well Reagan knew Rock Hudson, but I know how well I knew my best friend, Peter Vogel, how well I knew Vito Russo, Ken Dawson, Paul Popham, Dick Failla, Dick Gross, Don Castellanos, Michael Callen, and scores and scores of others from across the country.

Maybe Reagan needed a public face to make it okay to say the word “AIDS”—but it was the private faces of friends that fueled our determination to push forward. It was the absence of those faces in our lives that was the heartbreak of AIDS, and it is the memory of millions that should keep vivid the stain of shame that Reagan’s presidency will always carry for those of us who were there.

Karen Ocamb is currently the news editor at Frontiers, the Los Angeles newsweekly, and is the editor-in-chief of her blog LGBT pov, where she continues to report on hiv/aids issues.