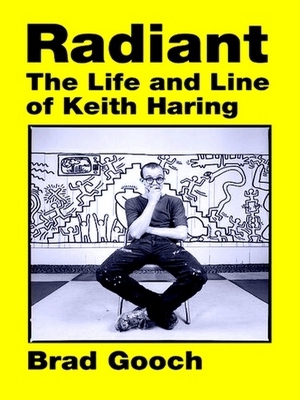

RADIANT

RADIANT

The Life and Line of Keith Haring

by Brad Gooch

Harper. 512 pages, $42.

BRAD GOOCH is an accomplished memoirist, novelist, and biographer of such literary figures as Rumi, Flannery O’Connor, and Frank O’Hara. His latest book is a compelling analysis of the remarkable legacy of artist Keith Haring.

Gooch was a contemporary of Haring when the latter was alive; they inhabited the same queer scene in 1980s New York. Much has been written about Haring from an art history perspective, but Gooch adds to the corpus with this sensitive and engaging portrait of his life and his legacy as an artist. Gooch was given full access to Haring’s archives, and he interviewed more than 200 people. The result is a compendium of vivid, first-person narratives that provide an insider’s perspective on the artist’s life. Because he focuses on friends and colleagues, Gooch delivers less academic “artspeak” than entertaining backstories about the artist’s inspirations and frustrations.

Attracted to the emerging graffiti scene, Haring began drawing images of crawling children and barking dogs on outdoor walls and in public spaces. He also posted Xeroxed agitprop broadsheets—a strategy inspired by William Burroughs’ cut-up methods. He found a kindred community in the burgeoning club scene in the East Village. Gooch details the gonzo performances, installations, and experimental videos that Haring participated in with friends—among them Kenny Scharf, Madonna, Ann Magnuson, and Jean-Michel Basquiat—at such venues as Club 57 and the Mudd Club. Haring’s public profile rose enormously after he began drawing with white chalk on the blank advertising panels on subway station walls. He’d jump off a train and sketch in full view, all the while trying to avoid getting arrested. Under these circumstances, his minimalist images of zapping spaceships, pulsing TV’s, barking dogs, crawling babies, leaping porpoises, and smiling faces developed in quality and complexity. It is estimated that over the next five years, he created over 5,000 chalk drawings (all unsigned) throughout New York City’s boroughs. Photographer Tseng Kwong Chi documented many of his underground performances. Eventually, some of these drawings were digitized for a Time Square electronic billboard show. An early review of Haring’s work in Artforum (1981) was quite insightful: “The Radiant Child on the button is Haring’s Tag. It is a slick Madison Avenue colophon. It looks as if it’s always been there. The greatest thing is to come up with something so good it seems as if it’s always been there, like a proverb.” His first one-person gallery show took place in 1982. A year later, he was featured in the Whitney Museum biennial. Invitations soon followed from institutions in Europe, Australia, and Japan. In 1983, Haring befriended Andy Warhol, an artist whom he greatly admired and emulated. They spoke on the phone regularly, often partied together at night, collaborated, and traded artworks. When Warhol died, Haring stated: “Whatever I’ve done would not be possible without Andy.” As demand for Haring’s work increased, he expanded his output to ink drawings, woodcut prints, paintings on tarpaulins and wood, aluminum sculptures, theatrical sets, and costumes, as well as largescale outdoor sculptures for playgrounds and murals for inner city walls, clubs, and children’s hospitals. Haring was determined to make his art accessible to a wide audience, outside of the elitist, insular domain of curators, galleries, and museums. Whatever the medium or scale, Haring maintained the ethos of his early subway drawings: no preparation, no preliminary sketches, just sure-handed strokes in his inimitable style. Interviews with gallerists recall Haring sequestering himself in the exhibition space days before an opening, creating the entire show en masse. Often, the paint was still drying as the public entered. Haring surrounded himself with kids. Young graffiti artists partied with him in his homes and studios. He collaborated with teenage tagger LA II (Angel Ortiz), embellishing readymade statues with hieroglyphic images. He worked with 1,000 students on an enormous mural celebrating the Statue of Liberty (1986). In Gooch’s biography, we also learn more about Haring’s loving relationship with multiple godchildren around the world. Sex and drugs were also a big part of Haring’s life, as deliciously detailed in Gooch’s account. He met his first significant lover, Juan Dubose, at the St. Mark’s Baths. Every weekend the pair went to the Paradise Garage—a club primarily for Black and Latino gay men. No alcohol was served, though many of the partygoers used hallucinogenic enhancements as they danced through the night. Madonna previewed two unreleased songs at the artist’s 26th birthday party (1984) at this venue, only to be upstaged by Diana Ross serenading Haring with “Happy Birthday.” Trying to maintain accessibility to his work as prices for his art soared, Haring opened his Pop Shop in 1986, in Manhattan, where he sold pins, T-shirts, calendars, watches, magnets, and prints. Critics slammed him for doing this, calling him “a disco-decorator.” While it was never a money-maker, the Pop Shop remained open until 2005. (A Pop Shop in Tokyo was less successful; it closed after a year.) Even as his fame grew, Haring remained dedicated to grass-roots activism, designing posters for anti-nuke rallies, anti-apartheid protests, safe sex promotions, and a myriad of LGBT-related causes. While working in Tokyo in 1988, Haring noticed purple lesions on his leg. His HIV status was confirmed upon returning home. Using his celebrity as a bully pulpit, he publicly announced that he was living with AIDS in Rolling Stone a year later: “In a way it’s really liberating. … Part of the reason that I’m not having trouble facing the reality of death is that it’s not a limitation. … Everything I’m doing right now is exactly what I want to do.” Rather than slowing down after his diagnosis, Haring ramped up his art-making and political activities. In his journals, he described his life as “working obsessively and constantly every day. … the only time I am happy is when I am working.” To celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in a 1989 exhibition at New York’s Lesbian and Gay Community Center, Haring painted the men’s bathroom on the second floor with his “Once Upon A Time” mural, which celebrates the pre-AIDS world of unbridled gay male sexuality. Haring died in 1990 at the age of 31. His memorial service at St. John the Divine Cathedral in Manhattan was attended by “more than a thousand invited guests.” Kenny Scharf and Ann Magnuson were among the less reverent at the ceremony, joking that “Keith would be really bored right now,” as they recreated some “shtick and act” from Haring’s Club 57 days. In his endnote, Gooch succinctly articulates the transcendent power of Haring’s example and work: “In our own era of engagement by so many artists with any available surface; with personal icons and licensing; with activism, collaboration, communication; and with the fostering of community, Keith seems more than ever one of us.”

John R. Killacky is the author of Because Art: Commentary, Critique, & Conversation.