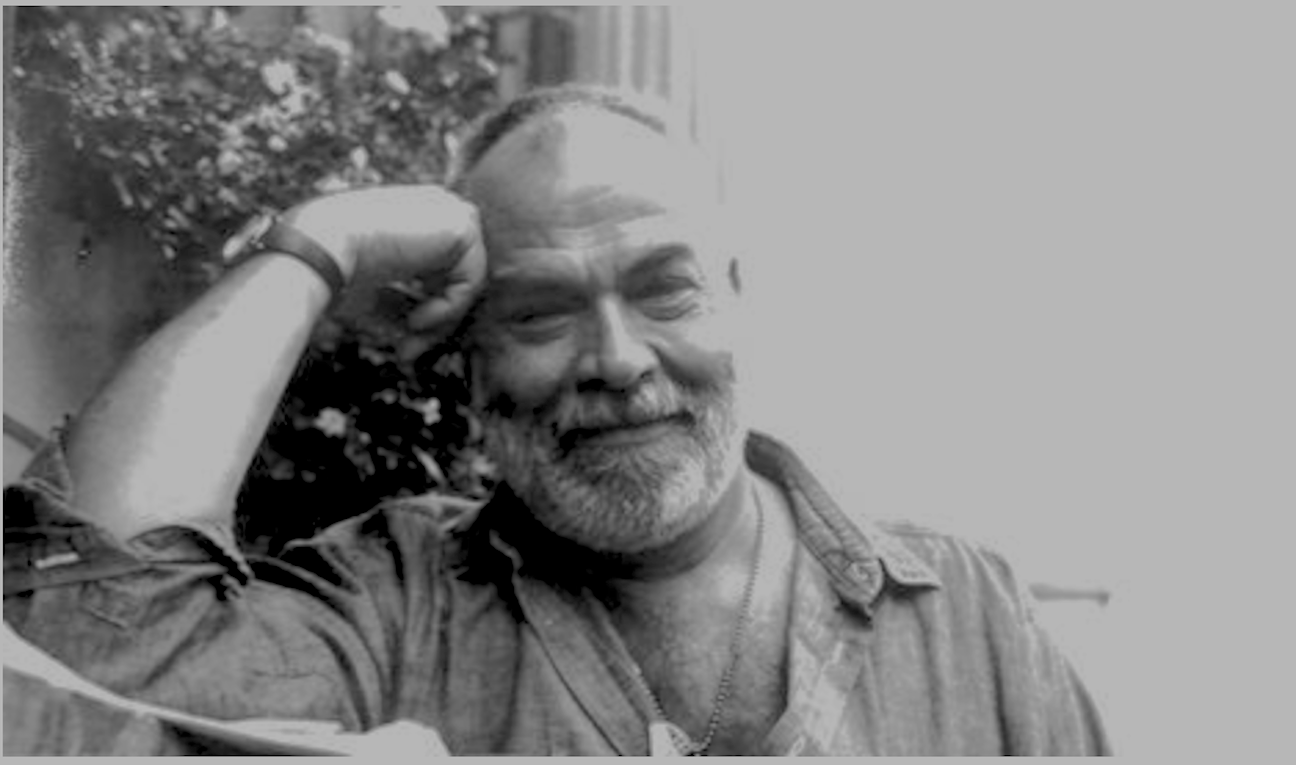

ARCH BROWN may be better known for his work in theater; he was part of the generation of playwrights (Jane Chambers, Doric Wilson, Robert Chesley) who brought gay subject matter onstage in the 1970s. But before that he was a pioneer in another medium, pornographic films. Brown’s A Pornographer: A Memoir is a book that was discovered among his papers after he died in Palm Springs in 2012; it was not published in his lifetime. Brown began writing it, so far as editor Jameson Currier can determine, around 1974, and submitted it to mainstream publishing houses in 1977, when Brown was still making films. (The later part of his life he devoted to theater, especially after the success of his 1979 play News Boy.)

Most of what Brown claims he learned while teaching himself how to make porn films seems eminently sensible. It wasn’t just lighting, editing in the camera, knowing how long an audience will sit still for certain sequences (about three minutes), or mastering how to pan the camera so that the figures didn’t blur. He also learned to interview people in depth about their sexual fantasies, to match them with someone who could fulfill those fantasies, and to make sure they didn’t meet each other until the day of the shoot. And never to have sex with any of the performers in his movies.

Brown learned all this after being fired from one of the jobs he took after moving to New York with a degree from the theater department at Northwestern University, which got him his first job at Circle in the Square. After that, he seems to have been in advertising and marketing for a time. When one of his colleagues was fired for reading Playboyin the office, he resigned, at which point Brown bought his first camera and began to wander the streets of New York.

In 1970, those were some streets to wander. The piers were still rotting on the Hudson River at the end of Christopher Street, and the only reason one went to the meat-packing district was to go to the sex clubs. Brown was known from the start for using such locations—and for the high quality of his films at a time when there was little demand for production values. In the early 1970s, gay porn films were simply backdrops for cruising in theaters like The David or 55th Street Playhouse. (Heterosexual porn films, ironically, were held to a higher standard, since the straight men who went to theaters to see those were actually watching the movie, not the other men in hopes of getting laid.) Brown also gave the actors a plot or situation with which an audience could identify (a day in New York, a visit to the country, a walk around the piers). A self-confessed romantic, he always provided a happy ending, and he took pains with the decor, lighting, color, and soundtracks.

For whatever reason, it worked. “Brown is doing something new, complex and important,” wrote Interviewmagazine’s critic in 1975. “Explicit sexual representation goes nicely in movies. It’s a wonder that all movies aren’t pornographic. That’s what movies are for. Food should be eaten, wine drunk, sex filmed.” In Brown’s view, the porn industry came out of the sexual liberation movement of the ’60s. But he was no militant. At one point in the book, a theater showing some of his early movies is raided by the police. The judge throws out the case against the three heterosexual films that were seized, but not Brown’s homosexual flick—a double standard that he mentions in passing, but no more.

People who read this book for dirt on making porn films, however, may be disappointed. This is not an exposé that takes you behind the scenes on specific shoots; it’s more of a thoughtful reflection on what Brown learned over the years by making movies. It’s based on the interviews he conducted with people auditioning for roles—their sexual fantasies, physical attributes, insecurities, feelings about being filmed. (Some actors, Brown learned, didn’t even want to see the films they’d starred in; others were like the unnamed woman who gave a dinner party at which she screened one of her porn movies for her guests.)

The actors are divided almost equally between men and women. Names are changed and personalities summarized, so the interviews read rather like case studies in a psychology textbook. “Gordon was also one of the regulars in my stable of sex stars,” a typical section begins. “He was good looking in a bland blond sort of way and didn’t have the best body or the biggest cock. But everyone who met him was turned on by him.” Or: “Ricky had been brought up in Texas and was into cowboys. He had grown up in a big city but had seen and unconsciously dreamed of the tough guys in big hats that were a part of the Texas landscape.” Even when we encounter a memorable anecdote, we don’t know who it was. One gay porn star liked to go to the theater where his film was showing and hang out in the men’s room, so that he could startle the moviegoer who’d walk in to pee and find him at the adjacent urinal.

These capsule summaries of actors prompt observations that one might find in a self-help book, or a manual on how to succeed in life and porn. Success, in Brown’s view, meant learning to become the person one fantasized about—and the process through which that happened he called “The Transition.” “I went through a big transition a couple of years ago,” one of his actors tells him. “The more secure I became the better work I was doing and the more friends I had and the more people began to respond to me emotionally. Instead of being a helpless little fag with nothing to offer anyone but clutching fingers and possessiveness, I had all of a sudden gotten my act together. I began to think of myself as that knight on the white horse and I could walk into a bar or party and not only have a good time, but meet new people and an occasional new boyfriend.”

In other words, the person who’s successful at work, in his career, his friendships, is going to be successful at sex as well. “I came to realize that not only was the star personality usually successful in most aspects of his or her life and sexually free, but they could be aware of their own problems and shortcomings and do something about them, and they were also aware of their sexual fantasies and often did something about them, as well.” What made a good porn star depended on what made a real movie star—good looks, ability to perform for the camera—but also, Brown believed, on an actor’s being at ease with sex, and not just sex but the rest of life.

It all sounds a bit like How to Win Friends and Influence People, or rather the gay uplift that followed Stonewall and produced books like The Joy of Gay Sex. It is impossible to read A Pornographer without being aware of the era in which it

Published by Chelsea Station Editions.

was written: the Me Decade. Gay liberation was underway, there was no such thing as AIDS, and homosexuals in cities like New York were aware that they were creating new forms of affective linkage—couples who allowed each other secondary boyfriends, people who could have sex with strangers with no consequences, having learned famously to separate “sex and sentiment.”

Like a child of the ’60s, he considered making porn movies a lot healthier than dropping bombs, and wondered when mainstream movies would include sex. But this is by no means an angry book. It’s in fact curiously dry—the grittiness of real life eschewed in favor of a more cerebral tone. Even observations like “Many men with exceptionally large penises have trouble getting completely hard, as if there is not enough blood in their body to fill it, but Bernard had no such problems” have a professorial tone. This may have been because Brown thought he’d have a better chance of getting a book like this published if soberly written, or because the nitty-gritty details of making fuck films genuinely didn’t interest him. Whatever the reason, the book’s tone is surprisingly neutral. Or it is, until we come to the afterword by a man who happens to be the president of a foundation Brown created to award grants to gay writers: James Waller.

Waller was Brown’s boyfriend when he was a graduate student at Columbia and Brown was living on 14th Street with his longtime companion Bruce Brown (whose last name Arch Kreuger adopted as his “nom de porn”). When asked by Waller what he did for a living, Brown said he was a “professional gay”—and, while ironic, this seems to have been the case. The relationship between Brown and Waller, separated by seventeen years, was among other things a sexual initiation. Here, for instance, is Waller’s description of the small apartment to which Brown took Waller after meeting him in the Barbary Coast, a bar at Seventh Avenue and 14th Street, one night in 1982—a trick pad-cum-studio that Brown rented upstairs from the large apartment that he shared with Bruce Brown:

Altogether, it was an eye-popping mise-en-scène for the likes of innocent little me. And my eyes would have occasion to pop again and again over the first week of our affair. The shower, for example, was outfitted with a coiled metal hose for anal douching—a device I’d never seen before. (Arch taught me to use it, of course.) In the bedroom was a huge blanket-chest filled with sex toys, including dildos ranging in sizes from index finger to fire hydrant, a variety of clamps and other pincers (e.g., plastic clothespins), sundry ropes and chains, and so on and on. For role-playing, there was a selection of hats—hard hats, workingmen’s caps, cowboy hats, etc. And beside the bed sat an ultra jumbo-sized can of Crisco—a lube of choice in those days. The bed itself was just a wooden platform topped with a queen-sized mattress, which was covered by a vinyl fitted sheet that Arch would clean, after sex sessions, with Windex and paper towels. Sex with Arch tended to be a messy and often somewhat greasy affair, and the room had a vague but indelible odor combining bodily effluvia, Crisco and ammonia.

Here, in one paragraph, you have the 1970s. The “ultra-jumbo-sized can of Crisco” was precisely what was scary to some of us about “the professional gay” of that time—the man with the moustache who lived downtown, the man one saw in the Ramrod, the Eagle, or the Spike. The can of Crisco—the greasy white stuff that made your grandmother’s apple pie crust so flaky and moist—was instead glistening on the fist entering the anus of the man in the leather sling—another version, one could argue, of the can of Campbell’s soup and Brillo boxes that Warhol had repurposed, an American staple that gay men had made subversive in a way that gay life can no longer be.

But this is what’s not in Brown’ memoir: the mess and the grease. Waller’s brilliant afterword is everything the memoir is not: personal and moving. We learn more about Brown in Waller’s reminiscence than we do in A Pornographer (which, to be fair, is not meant to be an autobiography but simply an account of Brown’s career in porn). We learn, for example, that Brown “despised” his mother. Brown never came out to his Midwestern parents, because, he writes, sex was never discussed in his family. Still, Brown’s life, in Waller’s version, seems like the paradigmatic story of a gay man of his time. He moved to New York, found a longtime companion, had boyfriends on the side (an arrangement he wished heterosexuals could have as well), and then moved to Palm Springs, where he started a theater, and was ripped off by one of his male caretakers—a young man who ran up gambling debts on Brown’s credit card—before he died. There’s enough there for a miniseries.

When Brown was working, he writes, there were only about twelve gay porn theaters in the entire U.S. Now people watch it online without having to leave the house. But what effect is it having on us? Brown mentions a heterosexual man he met who came in from New Jersey once a week to watch porn movies in a theater in New York, and then went home to his wife and tried out new things he’d seen done on screen. If, as the French aphorism has it, we would not fall in love had we not read about it first, I suppose we learn how to have sex from watching porn, though life influences porn as well. Brown could not help noticing how people were requesting kinky sex and drugs as the years went on—which was what was happening in gay life too. He acknowledges people who think watching pornography is a waste of time—time that could be spent having the real thing. But for those who can’t get the real thing, it’s a mercy. There’s an expression, “mercy fuck,” which means having sex with someone you really don’t want to have sex with. But until this is legislated as an entitlement along with Social Security, most of us will have to be satisfied with porn, since in real life two things that rarely go together are sex and charity.

Andrew Holleran’s fiction includes Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.