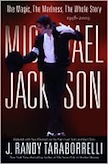

M ichael Jackson: The Magic, the Madness,

ichael Jackson: The Magic, the Madness,

the Whole Story, 1958-2009

by J. Randy Taraborrelli

Grand Central Publishing

832 pages, $18.99

SOME 700 PAGES into this comprehensive and even-handed biography of Michael Jackson, author J. Randy Taraborrelli remarks that the King of Pop would have paid a million dollars for a good night’s sleep. In the wake of his first child molestation scandal in 1994, Jackson worried that his image had been irrevocably tarnished, and there began a fatal descent into insomnia and substance abuse.

Given the details of his sudden death at fifty—he stopped breathing on June 25, 2009, due to an overdose of propofol, an anesthetic so powerful it’s known as “Milk of Amnesia” among surgeons—Jackson’s desperate search for the big sleep takes on an eerily gothic resonance. Each night before bed, inside a rented Holmby Hills mansion, Jackson would reportedly ask for his “milk” before being sedated and rendered cadaver-like until morning. There were rumors of his declining mental and physical health, but the concert-documentary This Is It shows Jackson moonwalking with abandon just two days before his death. We now know the final dose was administered by Dr. Conrad Murray, a Las Vegas-based cardiologist who was expecting to earn $150,000 a month for tending to Jackson during an anticipated comeback tour, and who is now standing trial for involuntary manslaughter. Left behind were numerous hard drives full of unreleased songs, and the posthumous release of his chart-topping “Michael” in 2010 proves that Jackson remains every bit as popular and perverse as ever.

What does Jackson, that American Icarus whose rise to mega-stardom was as swift and spectacular as his downfall, have to tell us about the sexual attitudes that fueled more than forty years’ worth of fascination with his sexuality? Weirdly, the subject of milk isn’t such a bad place to begin such an assessment given Jackson’s comments from 2003 in the now infamous interview granted to Martin Bashir, whom the artist naively thought would help rehabilitate his career. When fifteen million people in the U.K. tuned in for Living with Michael Jackson (followed, three days later, by 30 million more Americans), viewers were shocked to hear Bashir questioning his subject’s moral judgment, particularly Jackson’s habit of inviting children to share his bed. A defiant Jackson, holding a teenage boy’s hand at the time, fought back: “But when you say ‘bed,’ you’re thinking sexual. They make that sexual. It’s not sexual. We’re going to sleep. I tuck them in … give them hot milk. You know, we have little cookies. It’s very charming, very sweet.” No one found Jackson’s confession less charming than the Santa Barbara County District Attorney’s office, which soon raided the singer’s Neverland Valley Ranch and arrested the star.

Jackson was acquitted on all charges, but his deliberate disregard for the socially established codes governing relations between adults and children only highlighted a long history of boundary-breaking behavior in the realms of race, genre, and gender. The fact that Jackson’s death coincided with that of Charlie’s Angel’s Farrah Fawcett prompted one comedian to cackle that the world had lost two famous white ladies on the same day. The joke served as a reminder of how his ever-changing appearance undermined conventional notions of identity as static. Steven  Bruhm writes in his essay “Michael Jackson: Queer Funk” that the singer remains a source of scholarly interest as both a “scapegoat for a larger culture of childhood sexualizing” and for the “postmodern indeterminacy of his face and race.” His single “Black or White” (from 1991’s Dangerous) was meant to be an anti-racist protest song, but its title also reflected back upon the artist’s own racial ambiguity.

Bruhm writes in his essay “Michael Jackson: Queer Funk” that the singer remains a source of scholarly interest as both a “scapegoat for a larger culture of childhood sexualizing” and for the “postmodern indeterminacy of his face and race.” His single “Black or White” (from 1991’s Dangerous) was meant to be an anti-racist protest song, but its title also reflected back upon the artist’s own racial ambiguity.

The details of Jackson’s childhood are well known. By the age of eight he was playing clubs in his hometown of Gary, Indiana, and in Chicago; by nine, he had wowed the Apollo in Harlem, and by the summer of 1968 a contract with Motown Records was signed by “Michael Joseph Jackson” in a child’s barely legible hand. In addition to a grueling schedule of rehearsals, interviews, and tour-dates (all overseen by Jackson’s imperious and physically abusive father), the Jackson 5 recorded 469 songs for Motown between 1969 and 1975, but it was 1970’s “ABC” that sailed straight to the top of the Billboard charts. Offstage, the pre-adolescent Jackson was traumatized by the sexual attention he received at such an early age. While his older brothers reveled in the adulation, Jackson became increasingly frightened of his female fans. In the summer of 1971, a performance at Madison Square Garden had to be canceled only two minutes into the performance when fans stormed the stage, prompting the child-star to plead, “Return to your seats, please.” A groupie would later report that after having sex with Jermaine Jackson (age seventeen) in his Cleveland hotel room, she heard fourteen-year-old Michael say: “Nice job. Now, can we please get some sleep?” He was only three feet from his big brother’s bed during the encounter.

The solo career that followed was no less spectacular. The highlight, of course, was 1982’s Thriller, which sold more than fifty million copies worldwide. Jackson earned an estimated $500 million over his lifetime, and a fifth of those earnings came from Thriller alone. But by the late 80’s, Jackson’s behavior became increasingly bizarre, including a hoax involving a hyperbaric chamber, bathing in Evian water, shopping for the Elephant Man’s bones, appearing in public in pancake makeup and wigs, all of which earned him the nickname “Wacko-Jacko” in the British press.

Speculation about Jackson’s sexuality were never far away. As early as 1979, the singer grew defensive when questioned about his sexual identity, answering a question from Taraborrelli with more questions: “What is it about me that makes people think I’m gay? … Is it because I have this soft voice? All of us in the family have soft voices. Or because I don’t have a lot of girlfriends? I just don’t understand it.” A Saturday Night Live gag on “Guy Talk” featured Liberace and Jackson (played by Eddie Murphy) boasting about their womanizing, an ironic jab that put Jackson in the same category as Liberace. In 1984, dogged by a rumor that he and Boy George were secret lovers, Jackson quickly issued a two-page press release stating that Jackson planned some day to marry and start a family. “The press conference backfired; if anything, it raised more questions than it answered,” notes Taraborrelli. It seemed that the King of Pop was protesting too much. Even his two-year marriage to Lisa Marie Presley, the only daughter of the King of Rock and Roll, felt more like a business deal than a marriage. When they tied the knot in the Caribbean in 1994, the judge asked the groom, “Do you take Lisa Marie to be your wife,” to which Jackson replied: “Why not?”

Just as the most popular African-American recording artist in music history went to radical lengths to alter the traditional signs of blackness through skin-bleaching and multiple rhinoplasties (at least four procedures by 1986), Jackson was equally transgressive when it came to sex and gender. Surprisingly, the first mention of Jackson’s gayness appears in a book about Madonna (also born in 1958, only thirteen days before him), Madonnarama: Essays on Sex and Popular Culture (1993), in which Douglas Crimp and Michael Warner dismiss Madonna’s Sex book as hollow hype, but turn to Jackson’s sexuality as something much more inaccessible and worthy of study. “Imagine,” says Crimp, “Michael Jackson’s Sex. Wouldn’t you like to have access to his fantasy life!” Warner concurs, arguing that the idea is “much more intriguing because there seems to be much more distance between his fantasy life and his cultural circulation.”

At the epicenter of Jackson’s cultural circulation, of course, stands “Thriller,” and its iconic video has convinced Steven Bruhm that Jackson cleverly draws on the tradition of the danse macabre to choreograph what he considers a queer collision of pleasure and pain whereby “heterosexual normalcy” finds itself terrorized. A dashing date taking a girl to the movies metamorphoses into a monster right before her very eyes, and in the video’s last frame, after having concealed what he’s just horrifyingly revealed through song and dance, Jackson sends a knowing wink at the audience, as if the joke is on her. While it’s unlikely that Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle was on the singer’s nightstand, Bruhm argues that we can take Jackson’s queerness at face value if, he writes, “we take ‘queer’ to mean sexually ambiguous, protean, corporally illegible.” Another song from 1991 (overlooked by Bruhm) was “In the Closet.” While exalting “the truth of lust/ woman to man,” the song also insists that “we make a vow for now/ to keep it in the closet.” The video features a lithe and pony-tailed Jackson alongside supermodel Naomi Campbell, and it’s hard to make out whose eye-shadow is heavier.

What’s forever “queer” about Jackson’s sexuality is that it’s never reducible to a single orientation. Even his curious asexuality escapes the container of stable selfhood and keeps on mutating. A ballad like “Human Nature,” the fifth hit single from “Thriller,” fuses soul, funk, and pop, and in that fragile voice that evidently made the singer self-conscious, Jackson sings of a love misunderstood and judged by the majority: “If they say ‘Why, Why?’/ Tell ’em that is human nature/ Why, why does he do me that way?/ I like livin’ this way. I like lovin’ this way.” Jackson was always unapologetically himself, but the nature of that restless self continues to elude us as viewers and listeners. There’s a confessional trace in his desire to break free of the “four walls that won’t hold me tonight” within a “city,” he sings, “that winks its sleepless eye.”

Colin Carman, PhD, a frequent contributor to these pages, teaches British literature at Colorado Mountain College, Breckenridge.