AN HOUR BEFORE I was due there, I was surprised to read on my calendar that I was part of a reading group at the Huntington Library in San Marino, part of the hundredth birthday celebration of the writer Christopher Isherwood, born in 1904. I’d totally forgotten. His widower, Don Bachardy, had asked me some months before, and I had long ago found and marked a passage in Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1937), set in Hitler’s Germany, where a homosexual nobleman remembers those wonderfully free days of earlier gay life in Berlin. When I arrived, the auditorium was packed, standing room only, with movie and TV cameras scattered about. An usher seated me in the front row, I found my place in the book, and tried to catch my breath after the rush to get there and the hubbub of the event.

Suddenly I felt an elbow dig into my rib, and a familiar voice said, “Hey kid, do you know where the bathroom is?” I turned. It was the actor Mickey Rooney, and on his other side his wife (number eight?), almost twice his size and resembling a somewhat pulled together Morticia Addams. I looked on my other side: actor Michael York and his wife, then actress Gloria Stuart, and then Don. I’d been at the Huntington before and directed Rooney to our left and up the hallway, marveling that I was sitting next to someone whose films I’d seen most of my life, beginning on TV back on Long Island. He was Andy Hardy, boyfriend of Judy Garland, speaker of the line “I have an idea! We’ll put on a show in the barn!”

I felt another dig in my rib. “Hey, kid. I just had a cataract operation. Could you take me there?” So I stood up and he grabbed my arm, and I walked Rooney across the front of the auditorium and up the corridor to the men’s room. At the washroom doorway I recalled his eye problem and decided to take no chances. “Straight ahead. I’ll wait out here.” A few minutes later he was reseated, and I was up on stage, the first reader.

I bring up this anecdote because it probably will find its way into a future memoir that I write. I’ve published two volumes of True Stories, which have been well-reviewed award finalists, and I may yet do another. These aren’t quite memoirs, but as I explain in each preface, memoirs in negative: by writing about people in my life who’ve been important to me in some way, I am writing about myself. Also, the anecdote illustrates something intrinsic to my life: I meet many famous people, usually under odd circumstances, for better or worse.

Later that evening, after we readers dined at a French place in Pasadena, Gloria Stuart said she’d lost her ride and asked if I could drive her home to Santa Monica. In the car I asked if she were the same Gloria Stuart I’d seen in ’30s horror films like The Invisible Man and The Old Dark House. She admitted she was, adding that she was the favorite ingénue of gay director James Whale. She told me her career had been revived in her eighties with My Favorite Year and especially Titanic, for which she received an Oscar nomination. She knew who I was and said, “Like you, I was an early activist. I was called a socialist when I helped found the Screen Actors Guild.” We gabbed all the way back to her place—a rose-encrusted cottage directly across the street from the scene of the O. J. Simpson murders. We then became pals until her death at age 100.

Books Discussed

It hadn’t always been so. I used to be so utterly oblivious of celebrities that I fought off a middle-aged woman trying to steal a cab that I’d flagged down in Manhattan, only to be told by my embarrassed friend that it was Angela Lansbury. In my memoir Nights at Rizzoli I write about that unrepeatable moment when I understood that the intelligent little woman in the pink raincoat I’d been talking to for a half hour was Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

It hadn’t always been so. I used to be so utterly oblivious of celebrities that I fought off a middle-aged woman trying to steal a cab that I’d flagged down in Manhattan, only to be told by my embarrassed friend that it was Angela Lansbury. In my memoir Nights at Rizzoli I write about that unrepeatable moment when I understood that the intelligent little woman in the pink raincoat I’d been talking to for a half hour was Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Years ago, when people wrote their memoirs, they didn’t include stories like that. They usually wrote about their difficult youth, the poverty and hardship, or the uncompromising parents and education, and how they surmounted all  these difficulties and found their métier and became the great Charles de Gaulle or Douglas MacArthur. In more recent years we’ve also gotten what I call the “hetero-weepies”—Jeannette Walls, Janet Fitch, James Frey, et al. —stories by people not already famous who hope to become so through their memoirs and who sometimes actually do. You know, the kind of books that Oprah Winfrey tends to endorse.

these difficulties and found their métier and became the great Charles de Gaulle or Douglas MacArthur. In more recent years we’ve also gotten what I call the “hetero-weepies”—Jeannette Walls, Janet Fitch, James Frey, et al. —stories by people not already famous who hope to become so through their memoirs and who sometimes actually do. You know, the kind of books that Oprah Winfrey tends to endorse.

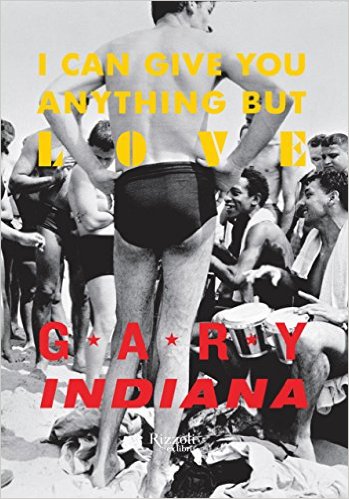

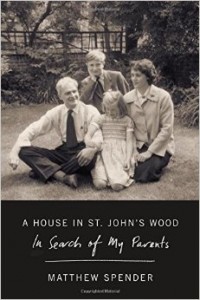

Anyway, my memoirs aren’t like those books at all. And neither are a bunch of gay-themed memoirs that came out in a sudden, wonderful burst in 2015. Among them I include Matthew Spender’s A House in St. John’s Wood, about  being the son of famous gay poet Stephen Spender and his contentious wife Natasha; Brad Gooch’s Smash Cut, about his relationship with filmmaker Howard Brookner; Bernard Cooper’s My Avant-Garde Education, an unexpected treat about his art school life and adventures; Gary Indiana’s I Can Give You Anything But Love; and Jameson Currier’s collection Until My Heart Stops. One can add to these some books I’ve not gotten to yet, such as George Hodgman’s Bettyville and Dale Peck’s Visions and Revisions, plus memoirs like Kevin Sessums’ I Left It On The Mountain and poet John Wieners’ Stars Seen In Person.

being the son of famous gay poet Stephen Spender and his contentious wife Natasha; Brad Gooch’s Smash Cut, about his relationship with filmmaker Howard Brookner; Bernard Cooper’s My Avant-Garde Education, an unexpected treat about his art school life and adventures; Gary Indiana’s I Can Give You Anything But Love; and Jameson Currier’s collection Until My Heart Stops. One can add to these some books I’ve not gotten to yet, such as George Hodgman’s Bettyville and Dale Peck’s Visions and Revisions, plus memoirs like Kevin Sessums’ I Left It On The Mountain and poet John Wieners’ Stars Seen In Person.

If one then includes several magisterial biographies of gay figures like James Merrill, Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and uber-fashion designers Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, and memoirs by younger gay men like David Crabb and Jamie Brickhouse, it becomes clear that some kind of tipping point has been achieved: an entire generation of (so far mostly male) gay people who lived on both sides of Gay Liberation have decided to tell all—or, more typically, some—about who they were, who they loved and hated, what they did, who they became, and maybe what it means to all of us. It really does feel like “a moment.”

If one then includes several magisterial biographies of gay figures like James Merrill, Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and uber-fashion designers Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, and memoirs by younger gay men like David Crabb and Jamie Brickhouse, it becomes clear that some kind of tipping point has been achieved: an entire generation of (so far mostly male) gay people who lived on both sides of Gay Liberation have decided to tell all—or, more typically, some—about who they were, who they loved and hated, what they did, who they became, and maybe what it means to all of us. It really does feel like “a moment.”

What’s partly at work is the Zeitgeist. As gay men of a certain age, we’ve gone through so much in our lives that we’ve been told that it is interesting, perhaps historic. However, we’ve also gone through too much to believe that a happy ending is inevitable—or even likely. At the end of his memoir, Gary Indiana writes that he checked his text care- fully to eliminate “any possible idea of triumph over adversity.” Spender’s straight son had to deal with reverse discrimination in a household where poetry and gay lovers were admired. When he revealed that he wanted to be a painter and was in love with a girl, he was belittled and told that he’d grow out of it. Gooch’s book shows how difficult it was to establish and maintain a relationship during the hip ’70s and ’80s, when ambitions, art, drugs, and sex all got in the way. A good half of Jameson Currier’s biographical essays center on how he couldn’t make something work against this backdrop, whether it be a relationship, a job, or a career.

Still, things could have been worse. At the height of his career Alexander McQueen committed suicide. John Galliano’s anti-Semitic temper tantrum in a Paris café ruined his career, and people who’d made millions from his work viciously turned on him. We know about Tennessee Williams’ sad passing, and Gore Vidal was alcoholic at the end: obese and uncontrollable, a monstrous caricature of himself. Only James Merrill escaped with dignity.

Still, things could have been worse. At the height of his career Alexander McQueen committed suicide. John Galliano’s anti-Semitic temper tantrum in a Paris café ruined his career, and people who’d made millions from his work viciously turned on him. We know about Tennessee Williams’ sad passing, and Gore Vidal was alcoholic at the end: obese and uncontrollable, a monstrous caricature of himself. Only James Merrill escaped with dignity.

As for triumphing—well, none of us did. After five years, I finally escaped the gilded cage that the best and most beautiful bookstore in the world had become for me, by turning down offers of high salaries and promotions for a $3,500  book advance. I’d seen too many talented people unable to fulfill their talents because they’d opted for financial security. Brad Gooch lost Howard to his own modeling career, to his lover’s drug use, and then to AIDS. After his father died, Spender and his mother pretty much fell out: she would have hated his book. Indiana’s memoir, which covers his twenties, goes from bad to worse and ends in a nightmarish Hollywood auto accident. I’ve been inside Ber-nard Cooper’s house—wonderfully midcentury modern—but I had no clue that he studied art: only recently has he become art critic for Los Angeles Magazine. I can’t tell from Currier’s book if he triumphed: I expect not, unless surviving and getting published counts.

book advance. I’d seen too many talented people unable to fulfill their talents because they’d opted for financial security. Brad Gooch lost Howard to his own modeling career, to his lover’s drug use, and then to AIDS. After his father died, Spender and his mother pretty much fell out: she would have hated his book. Indiana’s memoir, which covers his twenties, goes from bad to worse and ends in a nightmarish Hollywood auto accident. I’ve been inside Ber-nard Cooper’s house—wonderfully midcentury modern—but I had no clue that he studied art: only recently has he become art critic for Los Angeles Magazine. I can’t tell from Currier’s book if he triumphed: I expect not, unless surviving and getting published counts.

You’ve probably gathered already that each of these memoirs tells only part of a life story. Not even Spender’s, which begins before he’s born, is anything like complete. You may say this has something to do with how long many of us live, and how many lives and careers we have. But how much can we recall with precision? Obviously a key five years or so will stand out in greater relief than others. Being writers, some of us kept diaries and some have trained memories. Also, instinct often kicks in at key moments and says at the time, “Get this down on paper now!”

But even where my amazing recall and daily journal entries existed, I still needed more information than I possessed for Nights at Rizzoli, because there were facts about people that I never knew that I found I needed for the book. Not about Salvador Dalí or S.J. Perlman or Philip Johnson or Mick and Bianca Jagger, who became personal customers of mine at Rizzoli’s, where I worked in the early 1970s. I needed more about people connected with the store: Angelo Rizzoli, the founder, Natalia Danesi Murray, the head of American operations, Oriana Fallaci, the star reporter. All had fascinating lives. And, although on any evening in the early ’70s John Lennon, Abba Eban, Gregory Peck, George McGovern, or I. M. Pei could all be in the shop, instead I became interested in

But even where my amazing recall and daily journal entries existed, I still needed more information than I possessed for Nights at Rizzoli, because there were facts about people that I never knew that I found I needed for the book. Not about Salvador Dalí or S.J. Perlman or Philip Johnson or Mick and Bianca Jagger, who became personal customers of mine at Rizzoli’s, where I worked in the early 1970s. I needed more about people connected with the store: Angelo Rizzoli, the founder, Natalia Danesi Murray, the head of American operations, Oriana Fallaci, the star reporter. All had fascinating lives. And, although on any evening in the early ’70s John Lennon, Abba Eban, Gregory Peck, George McGovern, or I. M. Pei could all be in the shop, instead I became interested in  the talented, international staff—most of them artists or aspiring artists. So I write about them in detail. A sign of how tight a group we became is that 45 years later I was still in contact with five of them. One sent me a 25-page biography before he died. Not only did I find out about each person but about others in the store before and after my time there.

the talented, international staff—most of them artists or aspiring artists. So I write about them in detail. A sign of how tight a group we became is that 45 years later I was still in contact with five of them. One sent me a 25-page biography before he died. Not only did I find out about each person but about others in the store before and after my time there.

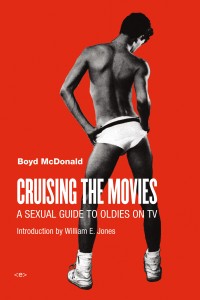

We assume this would be true for any biographer. It has also become part of the groundwork memoirists do before writing, and really enriches many of the books I’ve mentioned. In this group, it probably reaches its apogee with William E. Jones’ absorbing 25-page introduction to a reissue of Boyd McDonald’s Cruising the Movies: A Sexual Guide to Oldies on TV. I was the acquiring editor of that book back in 1985, recognizing it as a unique “memoir” of a brilliant, wayward talent: the founder of Straight To Hell: The Manhattan Review of Unnatural Acts, and of compilations like Cum, Smut, and Cream. In his preface and in the text, McDonald personalizes every frame of every film, and every actor or actress that he viewed on a small black-and-white TV, contextualizing them in the subjectivity of his own admittedly incessant masturbatory life and mind.

That’s another aspect of these memoirs and biographies: how small a gay world it displays. In my volumes of True Stories, I write about meeting and relating to Auden, Vidal, Williams, and Merrill. I published McDonald and Gooch; one of my Gay Presses of New York partners, Larry Mitchell, edited and published Indiana’s Scar Tissue and Other Stories, so we met. Meanwhile, Currier has published my books. I often feel like I’m reading about my extended (and fairly dysfunctional) family.

We also knew people that each other knew, often quite differently. Indiana’s memoir contains a five-page diatribe against his friend Susan Sontag centering on how she was a browbeating “great book” fascist whose opinion alone counted, and God help you if you didn’t agree. Others said the same. I met Sontag twice. First when I went home with a young man in Chelsea and had wild sex: we got dressed and just then Sontag walked in the front door. He introduced us and ran out to do laundry; he was a houseboy. But she sat me down and talked, asking me all kinds of questions. We met again two decades later during the intervals of Der Rosenkavalier at the Metropolitan Opera. She was with my friend Edmund White and Roger Straus, publisher of Farrar Straus & Giroux. I was with longtime friend Susan Moldow, a high-powered editor, now publisher of Scribner and Touchstone, so it was all book talk. If Sontag recalled me, she never hinted at it. Again she was on her best behavior, gracious and considerate.

Another instance: in Smash Cut, Gooch writes about the double publication party thrown for his first book, Jailbait and Other Stories, and Dennis Cooper’s Safe. He states that it took place at Limelight, a church converted into New York’s chic club of the time, and that luminaries including Edmund White, James Merrill, and John Ashbery attended. The book was put out by The SeaHorse Press, a one-man operation. My operation: I put together the event, yet I’m never even mentioned. Weird.

While having drinks at Don Bachardy’s before dinner last month, his co-editor of the Isherwood journals and letters, Katherine Bucknell, skimmed my bio-essay “The English Auntie” in True Stories. Among other things, I write about W. H. Auden telling me that just before the end of World War II, the German-speaking poet had been flown in a Navy plane on a scary secret mission to Germany and was almost shot down. Bucknell is writing the definitive biography of Isherwood and was in L.A. doing research using his papers at the Huntington before returning home to London. “Wystan [Auden] ended up flying several more times to Germany, where he was instrumental in effecting the surrender,” she told me. I already knew: a week before Auden’s terrible decision to move from New York to England, he’d told me this and instructed me not to tell anyone. He wouldn’t say why, but I’d respected his wishes. Now she knew, and it was clear that it would be revealed soon, either by her or by scholar Edward Mendelson, who she said was intent on proving that “Auden was a modern saint.” Matthew Spender knows better: in his memoir, Auden is contradictory, at times pompous, and has other failings—like the Auden I knew.

Revelations are bound to come out, secrets too, and of course, weaknesses and foibles via all of these memoirs. Bernard Cooper, describing his education at Cal Arts, writes that for students “to stand out from the crowd, we had to treat art-making as a competitive sport, hurling ourselves with ever more athleticism toward whatever was next.” I’d always suspected that about Conceptual art. Cooper also mentions that he came out and played around in what he calls The Great Before—before AIDS, that is. So does Gooch, who had already written about “the Golden Age of Promiscuity.” So do I, detailing my extremely bifurcated life: dressed in jacket and tie dealing with the world’s movers and shakers at Rizzoli and then going home, changing into levis, T-shirt, and boots, and cruising the abandoned piers, the trucks, the leather and S/M bars of Chelsea until dawn. The narratives of Spender, Cooper, and Indiana all spell out the ease of discovering our true sexual selves back then. The fashionistas came out equally quickly a few decades later, despite AIDS. And in the 1970’s, we amazed and frightened previous generations of gay men and women. Fighting over sexual politics with an older lover, I was asked in desperation, “What will happen if everyone gay comes out like you and your friends?” I responded “To begin with, the world will see how many of us there are.”

These memoirs and biographies will not only show how many of us there are, but how brave, how clever, how determined, how unafraid many of us were. And given the very high level of writing and the compelling readability of so many of these memoirs, possibly also how overlooked many gay writers have been by the so-called literary establishment.

Felice Picano’s latest book is a memoir titled Nights at Rizzoli (OR Books, 2015).