Rocking the Closet: How Little Richard, Johnnie Ray,

Rocking the Closet: How Little Richard, Johnnie Ray,

Liberace, and Johnny Mathis Queered Pop Music

by Vincent L. Stephens

University of Illinois Press

248 pages, $27.95

LAST SEPTEMBER, The New Yorker reviewed a book on reading in which the reviewer noted that there’s no war between the Internet and books; the Internet is now part of the way we read. We do it because we can look things up on Google or YouTube as we go along. Rocking the Closet, a new book by Vincent L. Stephens about four legendary singers—Little Richard, Liberace, Johnny Mathis, and Johnnie Ray—is a case in point.

Halfway through, I decided to look up Johnnie Ray, for example, on YouTube. Johnnie Ray is thought to be the first white pop star to sing like a black one. He was also “openly deaf” (after a childhood accident left him with partial hearing in his left ear), “effeminate, bisexual,” and often in trouble with the law for soliciting sex with men, though the most shocking thing about him might be that he had an affair with Dorothy Kilgallen, the thin-lipped, bird-like gossip columnist who became a panelist on What’s My Line? Learning about Ray was interesting enough, but not until I saw him sing his big hit “Cry” did I get exactly what it was that Stephens had described in prose. The moment Ray began with “If your sweetheart sends a letter,” I understood: This is the man who did what Elvis did, before Elvis did it.

Traveling back through the history of pop music with what Stephens calls “the Queer Quartet” is both a reminder and a discovery of musical figures that you may or may not have heard of, depending upon your age. Even people who’ve listened to the velvet voices of Johnny Hartman and Billy Eckstine may not have heard of Little Jimmy Scott or Gladys Bentley, a “large, African American woman whose dapper white tuxedo and raunchy blues performances defied a slew of gender, racial, and show-business conventions.” At her career peak from 1929 to 1932, Bentley “performed regularly in front of a chorus of male ‘pansies’ and married a white woman in a civil ceremony in New Jersey,” and was one of the reasons people went up to Harlem in the early 1930s.

Rocking the Closet takes us back to pre-liberation days in the same way that Guy Davidson’s Categorically Famous (reviewed in the November-December issue) reprised the careers of Susan Sontag, Gore Vidal, and James Baldwin to show how celebrities in the ’60s danced around the subject of their homosexuality while paradoxically opening the closet door. While Stephens focuses on four musicians, the subject of both books is basically the same: what the struggle was like before liberation. They’re the gay version of the explosion of books on slavery in academia. In neither subject is there much suspense—we know that the closet, like slavery, existed. And regarding the closet one is tempted to shrug: What would you have done in 1956? Nevertheless, though the point of these books might be expressed in one or two sentences, the details cannot; the latter are what make the history so interesting.

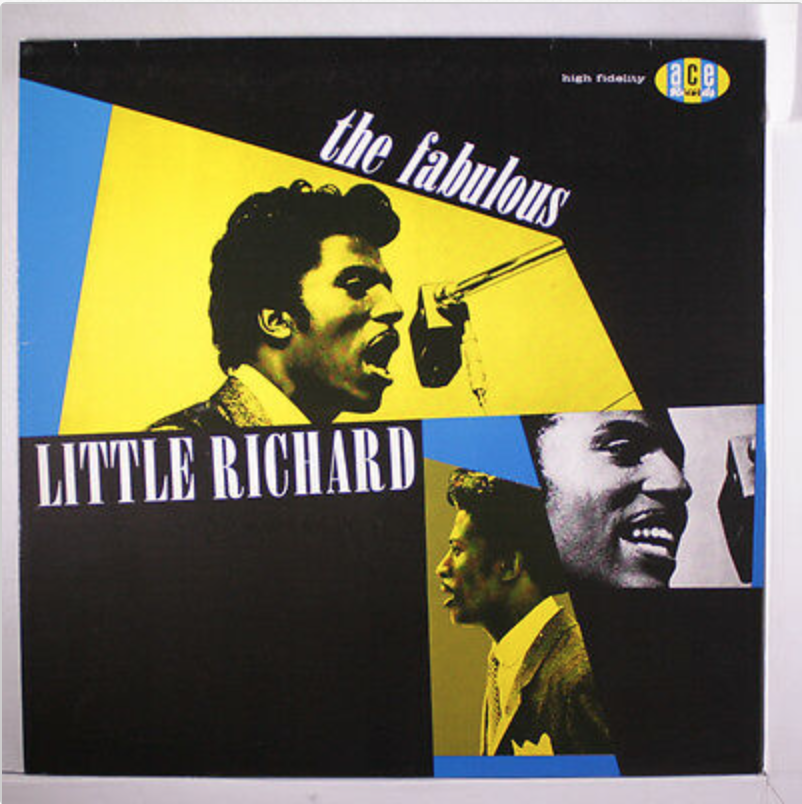

In the case of Rocking the Closet, all four men, despite their racial differences, had the same problem: how to present themselves in public at a time when the ideal of American masculinity was so strict and conformist that it gave rise to a bestselling book titled The Organization Man (1956). Soldiers coming home from World War II were expected to do three things: get a job, get married, and raise a family. The African-American man was subject to even more pressure to be a “race man”: someone of such sterling character and unquestioned masculinity that he was a credit to his race. So, where did that leave Little Richard, who began his career on the “Chitlin’ Circuit” by balancing a chair on his chin “as Princess Lavonne with the Sugarfoot Sam from Alabam minstrel show”?

Stephens suggests five methods by which his subjects coped. The “Queering” Toolkit included: “self-neutering” (playing down one’s sexuality); “self-domesticating” (getting married or at least evincing support for family life); “spectacularizing” (putting on a show so overwhelming it left no room for personal questions); “playing the freak” (ditto); and, finally, “playing the race card (or not).”

Johnny Mathis was the only one of the four who did not have to use the Toolkit, in part, I suspect, because he kept his private life so private, but also because, as he put it to a friend: “I was always adamant about the fact that I was not an entertainer. I was a singer.” It helped that he had an extraordinary voice, which he guarded over the course of a very long career with the discipline of a classically trained vocalist. Watch him on YouTube singing Michel Legrand’s “Pieces of Dreams.” First he shocks the Tonight Show audience a few seconds into the song with a note held for what seems like an impossibly long time, and then he settles into a ballad whose lyrics ( “Little boy lost in search of little boy found”) seem to have a subtext at least as gay as “All the Sad Young Men”; and then, after ending on another impossibly long note, he casually tips the hand-held microphone away from his lips like a gymnast who has just landed on his feet after five flips. The whole thing looks utterly effortless.

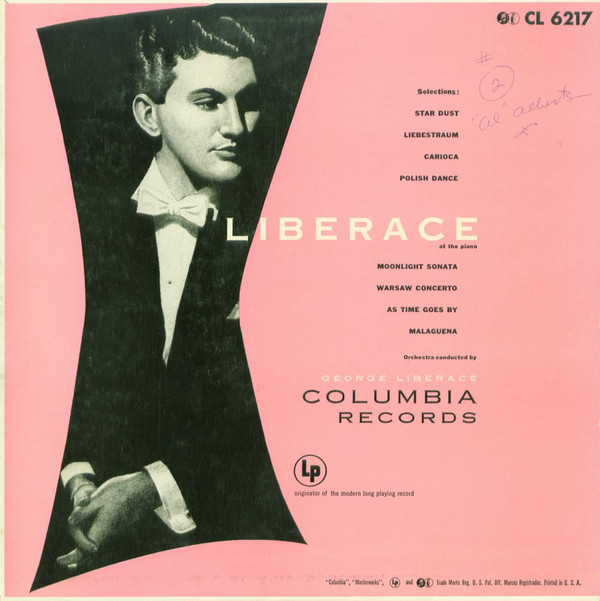

Mathis appeared at a time when the romantic ballad was still popular—though in the case of an African-American singer, one had to be careful not to be too romantic. When an earlier crooner, Billy Eckstine, appeared in a photo in Life magazine with an enthusiastic white female fan, he learned that he’d crossed a line. Black singers had to make sure their sexual appeal was not threatening. Homosexuality was taboo. The Queer Quartet dealt with that issue in different ways. Johnnie Ray got married. Little Richard “enfreaked” himself. It was only after he had become publicly religious that he admitted to having been gay. Liberace sued a London newspaper for libel when a columnist called him “the summit of sex—Masculine, Feminine and Neuter. Everything that He, She, It can ever want” and a “fruit-favored … heap of mother love”—and won the lawsuit. When urged years later by his former boyfriend to admit that he was sick with HIV, he allegedly refused by saying: “I don’t want to be remembered as an old queen who died of AIDS.” Mathis never hid his support for gay causes, but it wasn’t until 2017 that he admitted “I knew that I was gay” on CBS’ Sunday Morning.

The sexuality of all four performers was monitored by the press over the years. Jet and Ebony, the two largest black publications, both of which enforced the unwritten code of masculinity, gave Mathis a pass. But Confidential, like its sister publications Whisper, Hush-Hush, Top Secret, Lowdown, On the Q. T., and Hollywood Life, was as relentless as the McCarthy Committee when it came to homosexuals, until it lost half a million dollars in a libel suit, after which it ceased publishing stories on movie stars’ private lives, which led to its eventual demise. It’s a sequence comparable to what happened to these singers’ careers whenever they tried to domesticate or neuter themselves: their audience shrank. America, Stephens notes, wanted them to be outrageous as a relief from the public’s own surrender to conformity. Only Mathis never had to reinvent himself. His image from the start was so preppy that it was a shock to find him confessing that he’d “balled a lot of times to my own music” in an interview with The Advocate that’s quoted here.

The conflict between conformity and deviance, between the “Organization Man” and the “Freak”—a conflict that led Little Richard and Liberace to periodically clean up their act, lose audience share, and then go back to being outrageous—had a parallel in the split between the secular and the religious for many black performers. Almost all black pop stars in those days had learned to sing in church, and the effect of that upbringing never quite disappeared. One never knows, reading this book, whether Little Richard went back to religion for personal or career motives. But after telling David Letterman “I was gay,” he went on to claim: “I’m just so glad God brought me out of that. I never knew I looked like that, I’m just so glad that God was able to clean me out and wash me up. Thank you, Lord.” Al Green was to foreswear secular music for gospel in later years, and so did Donna Summer, who faced a backlash from her gay male disco fans after doing so. But in every case, going back to their religious roots was always a form of retirement from the scene. Little Richard, for instance, the man who claimed in his autobiography that when he went onstage he had one intention—to wipe out all the other acts—lost his impact on American culture for the same reason Liberace did when he momentarily decided to become respectable. Audiences had discovered, Stephens writes, that “deviance was fun!”

In his introduction Stephens quotes historian Heather Love’s recommendation that gay historians who find themselves “at a loss about what to do with the sad old queens and long-suffering dykes who haunt the historical record” should “admit the difficulties of the queer past … in order to redeem them.” Rocking the Closet does just that. No one is judged. Not Bobby Short, the dandified cabaret singer who held forth at the Café Carlyle for years and protested to a friend: “I had to make a living! I couldn’t march in the Christopher Street Parade!” And not Little Richard when he said: “I want to tell you something. I enjoyed being a homosexual. I didn’t give up something that I hated. I enjoyed being gay. I enjoyed being unnatural. It was fun to me. … But I want to tell you tonight, that’s from Hell.” Even the reformed Little Richard had nice things to say about people like Esquerita, the drag queen on whom he modeled his act. He said that the reason people became homosexual was loneliness: “They’re so lonely, they want people to love ’em. Homosexuals are the nicest people that you can ever meet. They’re kind, they’re artistic, they are lonely people. You can’t hate ’em to Jesus, you got to love ’em to Jesus.”

One used to hear this loneliness, this longing, in the R&B music out of which disco came, but it’s been a long time since people danced to “The Love I Lost,” by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, or “Make Yours A Happy Home,” by Gladys Knight and the Pips. Even the falsetto has disappeared, we learn in Rocking the Closet. The falsetto, while considered effeminate in a white singer (though that hardly stopped Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons) was considered an expression of sincerity and warmth in black music. Go to YouTube and watch Luther Vandross (another singer who ultimately confessed to a friend that he was “in the life” but never came out publicly) sing “Endless Love” with Mariah Carey. Like other black men who used the falsetto—Eddie Kendricks, Al Green, and Marvin Gaye, not to mention the most spectacular example, Sylvester—Vandross gave gay men some of their most memorable moments on the dance floor in the ’70s. But that magic disappeared when disco was succeeded by techno, house, electronic, and finally hip-hop, when the warmth and sincerity of black singers ended in the monotonous drone of rap—which is where popular music seems to have dead-ended for the moment. There have been many changes in American culture since the underground dance scene that gay men made a staple of their lives in clubs like Flamingo, but the one that still flabbergasts is how pop music went from a song like Isaac Hayes’ version of “Never Can Say Goodbye” to Eminem’s “Criminal.” But that’s a subject for another book.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the novels Dancer from the Dance, Nights in Aruba, The Beauty of Men, and Grief.