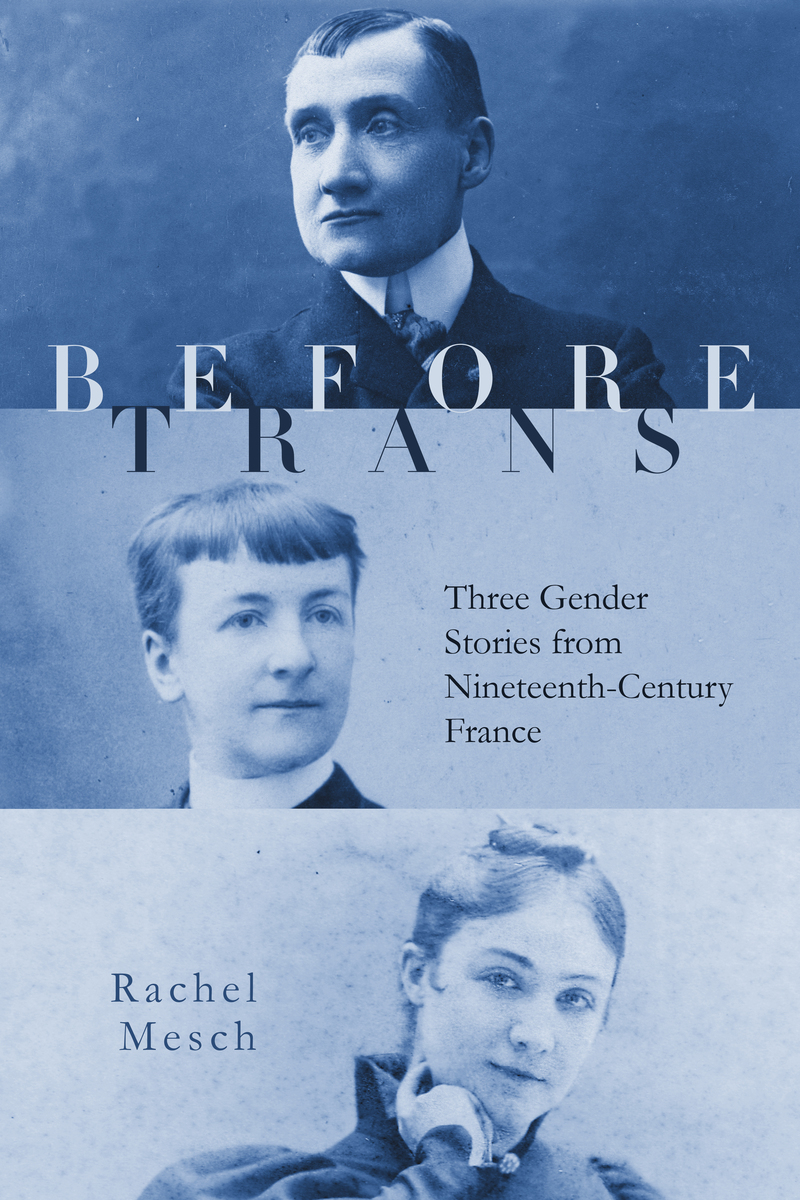

BEFORE TRANS

BEFORE TRANS

Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

by Rachel Mesch

Stanford Univ. Press. 333 pages, $30.

MARIA was a shy, bright girl growing up in East Los Angeles. According to her mother, there was nothing unusual about her gender presentation in elementary school: she liked dolls, her long hair, dresses, princess costumes for Halloween. (Names and details have been changed to protect anonymity.) Mother and child agreed about that. It was only in middle school, with the start of puberty, that Maria started to feel there was something deeply troubling about her body and how she felt in it. After watching a female-to-male trans teen on YouTube, Maria started to figure out that he really felt like a boy and that “trans” was the term to describe this. There followed two years of quiet struggle, gradual adoption of male clothes, and increasing hostility from peers. After trying on a couple of boy’s names, he settled on Eddie. In the meantime, he switched schools twice due to teasing and an assault (ironically, because he got bullied as a “fag”).

Despite the proliferation of trans celebrities and characters in diverse media, it can still be a turbulent, even perilous, process for a person with atypical gender feelings to develop their gender identity and sexuality. Medicine only formulated the concept of “transsexualism” in the first half of the 20th century. This diagnosis and its treatment with hormones and surgery were codified and legitimized in the second half (after the manufacture of sex hormones). While the medical model was being standardized, individuals with diverse gendered feelings were busting through that model by the 1990s, leading to a multiplicity of identities and terms: transgender, genderqueer, gender fluid, gender nonbinary, non-transitioning transgender, and so on.

Before the 20th century, what would a Western person with trouble conforming to gender norms have done without any of these terms? They may have suffered silently. They may have discretely “passed” in their desired gender role—until being exposed in life or at autopsy. They may have brazenly violated vestiary conventions and laws. Many of these stories have recently been detailed by scholars (such as the late Leslie Feinberg) as examples of “transgender warriors” from antiquity to the present. However, it is problematic to lump all of these manifestations of gender diversity as exemplars of our contemporary category of “transgender.” The historical characters did not have this identity label, and, like many a queer teen today, may have actively resisted being lumped under any category.

In her new book Before Trans, Rachel Mesch adroitly walks the methodological tightrope of examining historical characters through the lens of transgender analysis, yet accepting their gender originality. Her writing is theoretically savvy without being academically ponderous. A professor of French studies at Yeshiva University, Mesch has previously studied French women authors of the Belle Époque. In her current book, she brings to life three gender-bending women of the period: Jane Dieulafoy, Rachilde, and Marc de Montifaud. There is a wealth of Rachilde scholarship by feminists—despite the fact that Rachilde disavowed the label. The other two women are more obscure, though visitors to the Louvre might recognize the monumental finds from Dieulafoy’s Persian excavations. Mesch refers to her three subjects as “women” because that is how they identified themselves, sometimes explicitly dismissing the aspersions cast upon them by journalists or rivals who viewed them as mannish feminists, “New Women,” or “bas-bleu.” (Bas-Bleu—“blue-stocking”—remains a pejorative French term for women with literary or intellectual pretensions.)

The three were different on many grounds—politically, socially, temperamentally. However, in terms of Mesch’s project, they had one notable commonality: extended periods when they dressed as men. This was not a trivial fashion statement. At the time, Parisiennes needed a legal permit to cross-dress: a “permission de travestissement.” In French, travestissement means both “transvestism” (cross-dressing) and, more broadly, “disguise.” This regulation had a precedent in older, broader sumptuary laws that prohibited commoners from disguising themselves as aristocrats, clerics, or officers. These laws were suspended only for Carnival: a topsy-turvy time when a pauper could dress as a princess and a butcher as a bishop. Aside from the legal proscription against transvestism, there was strong cultural disapproval. These three women were cross-dressing well before the 1920s, when women’s styles of dress were starting to become freer and more androgynous.

The Paris Prefecture of Police issued the regulation in 1800. It required a physician’s notarized certification that male clothing was necessary for the woman’s health. The regulation’s text betrays conflicting aims to safeguard the individual versus the public. Initially, it claims the law will protect cross-dressing women from harassment (including by police!). Yet, it goes on to suspect these women of “the guilty intention of abusing their disguise.” The permit was valid for only six months and explicitly prohibited the bearer from appearing cross-dressed at balls, shows, or “meeting places open to the public.” Any woman found cross-dressing without a valid permit was to be arrested and brought to a police station. No fine was stipulated. The poorly preserved “Travestissement” file in the Paris Police Archives suggests that few permits were actually issued. However, the file documents some famous bearers, including George Sand, Rosa Bonheur, Rachilde, Jane Dieulafoy, and Marguerite Bellanger (a mistress of Napoléon III). Some feminists contested the law in the 19th century to no avail. It never seems to have been implemented in the 20th century, yet was not abrogated until 2013!

Jane Dieulafoy (1851–1916) had two reasons for adopting male dress: she was a sharpshooter in the Franco-Prussian War, and she went on grueling archeological digs. Born into a prosperous Catholic family from Toulouse, she married a young engineer, Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy, in 1870, just months before the outbreak of the war, in which she served beside her husband—in male uniform. They remained by all evidence a devoted couple until his death in 1920. The two developed a passion for ancient Persian architecture and embarked on their first expedition to Susa in 1880. In preparation for the voyage, Jane learned Farsi, photography, and Persian history. She was Marcel’s constant companion on all their excavations and collaborator on their archaeological publications. In her travelogues, she explains that male dress was simply the most practical way of passing in Muslim lands and engaging in taxing archaeological work.

Jane Dieulafoy (1851–1916) had two reasons for adopting male dress: she was a sharpshooter in the Franco-Prussian War, and she went on grueling archeological digs. Born into a prosperous Catholic family from Toulouse, she married a young engineer, Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy, in 1870, just months before the outbreak of the war, in which she served beside her husband—in male uniform. They remained by all evidence a devoted couple until his death in 1920. The two developed a passion for ancient Persian architecture and embarked on their first expedition to Susa in 1880. In preparation for the voyage, Jane learned Farsi, photography, and Persian history. She was Marcel’s constant companion on all their excavations and collaborator on their archaeological publications. In her travelogues, she explains that male dress was simply the most practical way of passing in Muslim lands and engaging in taxing archaeological work.

Their magnificent finds—the Frieze of the Archers, the Lion Frieze, the double bull head capital—were exhibited at the Louvre to astonished audiences, then and now. She was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1886. On her initial return to France, she also returned to female dress, but after subsequent excavations remained permanently male-attired. In many press photographs she sports identical clothes as her husband. Journalists extensively covered her public lectures, highlighting her sartorial choices, while conceding her reasoning: it facilitated their exotic travels and co-equal collaborations. Her “transvestism permit” is lost, but her rationale was not unusual.

The police transvestite file contains permits granted for the purpose of horse riding or for exercising traditionally male professions like printer, stonecutter, and locksmith. It also notes permits for bearded women and a woman who appeared so masculine that “she would look ridiculous in the clothing of her sex.” However, at least one satirical cartoonist was less convinced; he questioned who wore the pants in the house and depicted Jane as caricaturally masculine. However, photographs and illustrations represent her as a boyish man (even into old age), impeccably dressed, and proudly wearing her Legion of Honor ribbon.

In addition to scholarly books and travelogues, Jane also published fiction and (with Marcel) Le Théâtre dans l’intimité (Theater at Home, 1900), a collection of five classical plays and farces that they had adapted and presented in their Parisian mansion. The volume extols Classical theater, produced at home, as an antidote to the overblown contemporary productions designed to appeal to the masses (think Broadway musicals catering to tourists). A worthy domestic production, they argued, does not need elaborate sets or costumes; given the androgyny of classical togas, men or women could play any role. These are the subtle hints at gender crossing that Mesch emphasizes throughout Jane’s texts. Each novel has its own suggestive plot elements that mirror aspects of Jane’s cross-dressing experiences in war or exploration.

Sadly, we do not get more explicit testimony of her cross-gendered inner life, which might have emerged from a joint project the Dieulafoys never completed: a work on male-to-female cross-dressers. Mesch presents just one page of the archival drafts of this project, which included historical figures like the Chevalier d’Eon and the Abbé de Choisy, as well as “Stuart.” Stuart was a 19th-century American male opera singer who performed female roles. The Dieulafoys had hosted Stuart at their home, and Jane’s notes highlight that doctors had found Stuart’s throat to be that of a woman, suggesting Jane’s interest in medical explanations of “psychosexual hermaphroditism.”

Why did they never publish this work or another on cross-dressing in the theater (which Mesch only mentions in passing)? Did they want to protect the respectable veneer of a happy marriage? Or was it a part of her overall political complexity? Mesch observes that Jane’s different justifications for male dress are couched in Catholic and nationalistic conservatism. Her soldierly dress helped her fight the Prussians and defend France, just as Joan of Arc and other transvestite female saints had done. Jane’s Persian travelogues present her as a swashbuckling explorer, gazing upon exotic or primitive Muslims with the Orientalist, cultural superiority of the best of male colonizers. On sexual politics she was equally conservative. An outspoken Catholic, she was a self-declared “enemy of divorce.” She shared the worries of conservative pundits who were dejected by France’s shameful defeat in the war. They feared that France’s declining fertility reflected the collapse of manhood and the disdain of motherhood. “Stable families are formed under the shelter of indestructible homes,” she wrote, “and it is stable families who make up strong nations.” Although her marriage was permanent, they never had children. Her writings suggest a compromise of sorts: traditional femininity would have squashed the heroic exceptionalism that made her an equal to her husband.

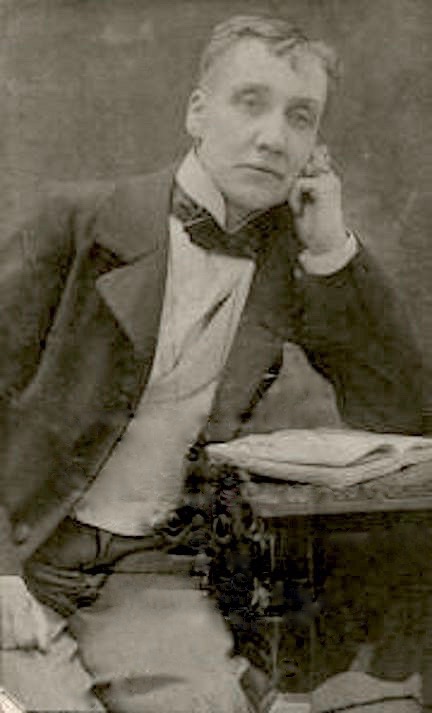

Rachilde (1860-1953) was the pen name of Marguerite Eymery, born into a well-to-do family from the Périgord region of France. Her autobiography from the end of her life has proven highly fanciful under the scrutiny of a legion of Rachilde scholars in the last few decades. In her own telling, the name Rachilde was that of a 17th-century Swedish count whom she channeled during a séance when she was sixteen. She later admitted it was a hoax. However, it remained a useful male pseudonym for launching her career as a journalist and then a novelist of scandalous erotic novels. Rachilde’s cross-dressing was just for a brief period, early in her career. She requested her transvestism permit in 1885 with the justification that it was necessary to exercise her profession as journalist. However, unlike Jane Dieulafoy, Rachilde’s transvestism was meant to draw public attention, even notoriety. It ended after her marriage to Alfred Valette in 1889. The following year, the two of them relaunched a defunct publication, Le Mercure de France, as a literary journal and later a publishing house that was a vehicle for Symbolist writers and emerging novelists like Colette and André Gide.

Rachilde (1860-1953) was the pen name of Marguerite Eymery, born into a well-to-do family from the Périgord region of France. Her autobiography from the end of her life has proven highly fanciful under the scrutiny of a legion of Rachilde scholars in the last few decades. In her own telling, the name Rachilde was that of a 17th-century Swedish count whom she channeled during a séance when she was sixteen. She later admitted it was a hoax. However, it remained a useful male pseudonym for launching her career as a journalist and then a novelist of scandalous erotic novels. Rachilde’s cross-dressing was just for a brief period, early in her career. She requested her transvestism permit in 1885 with the justification that it was necessary to exercise her profession as journalist. However, unlike Jane Dieulafoy, Rachilde’s transvestism was meant to draw public attention, even notoriety. It ended after her marriage to Alfred Valette in 1889. The following year, the two of them relaunched a defunct publication, Le Mercure de France, as a literary journal and later a publishing house that was a vehicle for Symbolist writers and emerging novelists like Colette and André Gide.

While Rachilde’s cross-dressing lasted less than a decade, her toying with gender was lifelong, Mesch argues. Her memoir claims her female birth was an “accident of nature” and that her father had raised her as a boy. She reportedly did military training alongside her father and acted as a war correspondent. In a world dominated by male writers, her calling card read “Rachilde, homme de lettres.” Most notably, her novels are populated with gender bending characters, which by her own account were projections of herself: “transvestites of her mind.”

The novel that brought her notoriety and a pornography lawsuit, Monsieur Vénus: Materialist Novel (1884), features a genderfluid heroine, Raoule. She marries an effeminate florist, manipulating him into effectively being the wife of the couple. Its conclusion made her a darling of the Décadent movement. Raoule orchestrates the death-by-duel of her husband/wife, then plucks his hair, teeth and nails to enliven a wax automaton. She makes love to it nightly, dressed in mourning as either a man or a woman. Rachilde labeled her heroine as a hysteric and embraced this diagnosis for herself. She seems to have welcomed the criticism that her novel was the product of a perverse and sick mind. Mesch, however, interprets her hysteria as a cover for—perhaps a manifestation of—Rachilde’s inner turmoil about her gender.

Although her cross-dressing ended after her childless marriage to Alfred Valette, her writings and pronouncements continued to defy gender conventions. Mesch argues that Rachilde’s anti-feminist tract from 1928, “Why I Am Not a Feminist,” reveals her as neither male nor female. She was perhaps gender nonbinary before that possibility explicitly existed. She certainly wished to be seen as a uniquely creative creature, beyond sex.

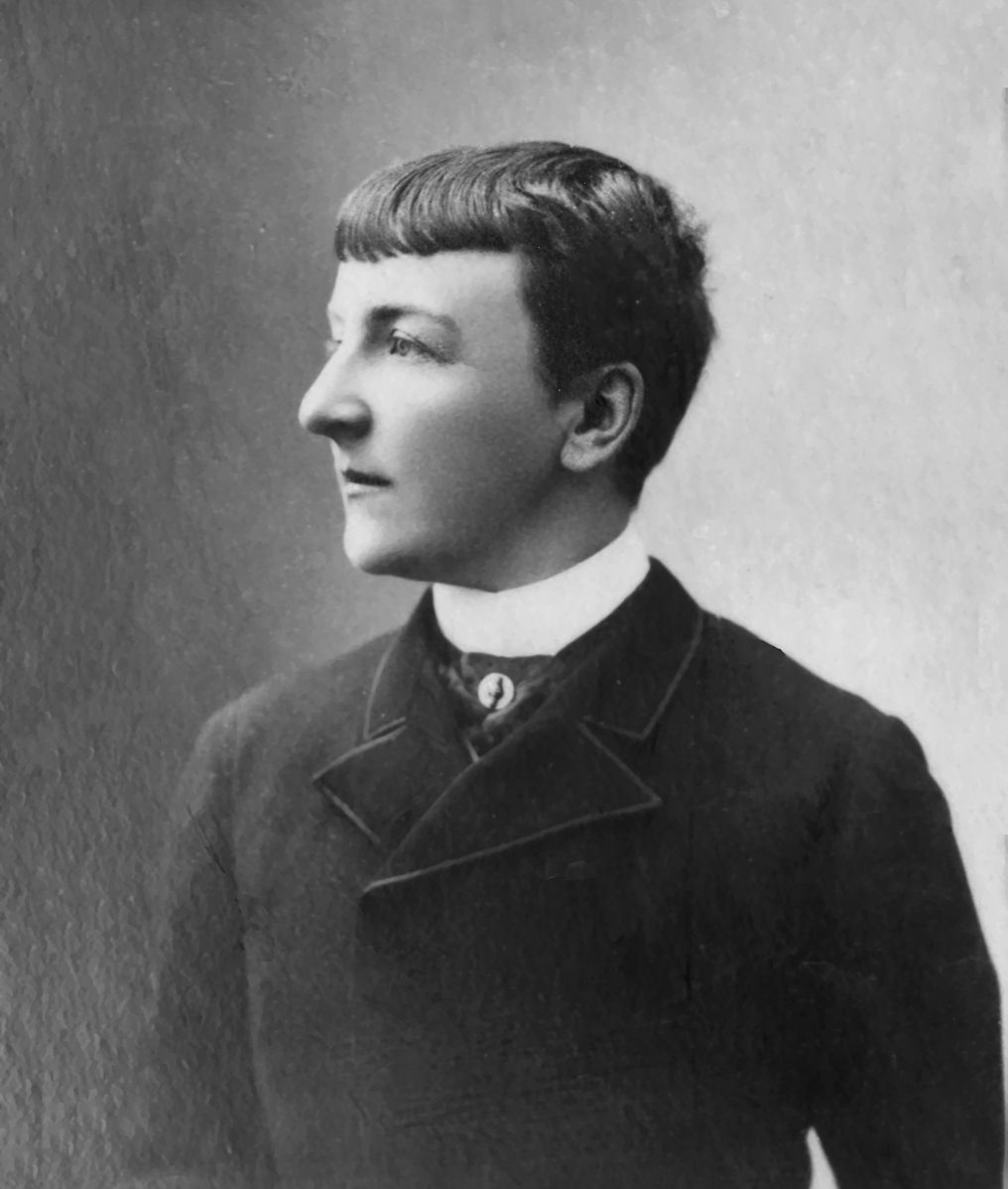

Marc de Montifaud (1845-1912), Mesch’s third character, was the most visibly masculine of the three (from available photographic evidence). She was born Marie-Amélie Chartroule de Montifaud into a well-off Parisian family. Her mother was a conservative Catholic, while her liberal-minded physician father would become an adherent of libre-penseur (free thought) philosophy. She studied art and followed her father’s anti-establishment inclinations. In 1864, at age nineteen, she was married to a 35-year-old Spanish count who was personal secretary to Arsène Houssaye, a celebrated writer, director of the Comédie-Française, and owner of the weekly arts journal L’Artiste. The journal began publishing her art reviews under the pseudonym Marc de Montifaud in 1865. She was a prolific art critic and attended the annual Art Salon, possibly disguised as a man: her 1867 entrance pass lists her as “Mr. Montifaud.”

Marc de Montifaud (1845-1912), Mesch’s third character, was the most visibly masculine of the three (from available photographic evidence). She was born Marie-Amélie Chartroule de Montifaud into a well-off Parisian family. Her mother was a conservative Catholic, while her liberal-minded physician father would become an adherent of libre-penseur (free thought) philosophy. She studied art and followed her father’s anti-establishment inclinations. In 1864, at age nineteen, she was married to a 35-year-old Spanish count who was personal secretary to Arsène Houssaye, a celebrated writer, director of the Comédie-Française, and owner of the weekly arts journal L’Artiste. The journal began publishing her art reviews under the pseudonym Marc de Montifaud in 1865. She was a prolific art critic and attended the annual Art Salon, possibly disguised as a man: her 1867 entrance pass lists her as “Mr. Montifaud.”

Mesch notes that Montifaud wrote about her male transvestism only once: in a passing comment in an autobiographical letter of 1882. What initially stirred criticism were her historical publications, such as her first, on Mary Magdalene, followed in 1874 by Les Triomphes de l’abbaye des Conards (“The Victories of the Abbey of Fools/Cuckolds”)* and her 1876 edition of a 17th-century libertine novel. This last book brought charges of “offense to public decency.” Instead of being sentenced to a prison where other male authors (including the Marquis de Sade and Zola) had been sent for chastisement, Montifaud was fined and condemned to the women’s prison that housed prostitutes and violent inmates. She instead fled to Brussels and eventually arranged to do alternative time in a mental institution. Nevertheless, she persisted: she kept on publishing, being sued, and being condemned.

She emerges, despite Mesch’s sympathetic telling, as a feisty, perhaps even prickly and entitled character. She continued to publish a string of controversial if not outright provocative books: a history of Vestal Virgins of the Church (and their divine ecstasies); a history of the cross-dressing Abbé de Choisy; and a series of cleverly erotic short stories. Her first novel, Madame Ducroisy (1879), was condemned for indecency. She was fined and sentenced to four months in prison—again served in a mental asylum. She kept on publishing, being fined, and fleeing to Brussels. She was accused by journalists of being a hysterical bas-bleu and was suspected of being a lesbian. There is evidence she had affairs with women and men. But for all the public attention, there’s little to go on about Montifaud’s sexuality or gender feelings. She remained married until her husband’s death in 1901. They had a son named Marc, to whom she was devoted.

The most striking public depiction of her cross-gendering was from her assault on Francis Magnard, the editor of the conservative newspaper Le Figaro. The paper had printed a front-page story about a woman publishing under the pseudonym “Madame de Sade” who was condemned to prison for her pornographic stories. However, it was Mme. de Sade’s husband who had abusively forced her to write them and had reaped the profits of her notoriety. Montifaud rightly recognized herself in the satire but was incensed that her husband had also been maligned. The two of them confronted Magnard at the Comédie-Française. A patron prevented the husband from striking Magnard in a duel-provoking manner, but Montifaud managed to slap the editor with a copy of the defamatory newspaper. Journalists reported Montifaud was not recognizable as a “member of the fair sex,” as she had an “unfeminine face,” was dressed in a tailcoat, and sported short hair.

Montifaud fled again to Belgium, where she continued to wear male clothing. It was, she claimed, to remain hidden and to protect her son. Even after returning to Paris in 1883, she maintained her male appearance. Falling on hard times, she reportedly passed as a man to work as a porcelain decorator. Mesch details a telling letter from a friend of Montifaud: a government bureaucrat who apparently made inquiries on her behalf in 1896 about her need to get a transvestism permit for her public appearances. He reassures her it is not necessary, since she has made such a longstanding habit of cross-dressing and the police had granted her verbal approval. Most likely the police had long since tired of the formality, even if conservative critics continued to rail against feminists and masculine women for forsaking femininity and the duties of motherhood. Her last work, Alsace (1904), was a patriotic one-act play published under a third male pseudonym (Paul Érasme) and also censored. Montifaud was fairly opaque about her “gender identity”—to use our current term. However, she doggedly pursued male occupations and “unfeminine” topics with tenacity. She cut a distinctly masculine appearance for the latter half of her life.

Mesch’s detailed and textured survey of these women and their writings does full justice to their unique talent and complex psyches. It would be facile to label them as transgender heroes, as they avoided any group identity. In their individual ways, they struggled to be adventurous and creative at a time when this was frowned upon for women. Their bending of gender rules was exceptional and had few historical role models. They certainly did not embrace the medical model of “sexual inversion.” This concept was formulated during their lifetime and was familiar to highly educated people like them. The medical diagnosis of transsexualism was not consolidated until the mid 20th-century.

Ironically, their often bumpy yet daring exploration of unorthodox gender is also post-transsexual. Many genderqueer people since the 1990s have struck out on their own creative gender and sexuality path beyond the medical orthodoxies of the 1950s to the 1980s. Like my patient Eddie and other young, gender-nonbinary people today, Mesch’s three exceptional subjects spun their unique, private gender psyche even as they wove it into the fabric of their life’s work. Gender-bending people today are also composing their own, original gender stories.

* Sixteenth-century “festive societies” performed burlesque parades and held rowdy festivals during carnival. They mocked the nobility, clergy, and judiciary. Montifaud re-edited a 1587 account of the 1541 festivities in Rouen, including the satirical, punning poetry tossed out to spectators. I imagine it was a blend of Mardi Gras and Monty Python. These were the sorts of carnival festivities that were specifically exempted from travestissement rules. (See Dylan Reid, “Carnival in Rouen: A History of the Abbaye des Conards.” Sixteenth Century Journal, 32: 4, 2001.)

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and Associate Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA.