Glenveagh Mystery: The Life, Work and Disappearance of Arthur Kingsley Porter

Glenveagh Mystery: The Life, Work and Disappearance of Arthur Kingsley Porter

by Lucy Costigan

Merrion. 336 pages, $84.95

IMAGINE your spouse, partner, lover goes out for a walk one evening and never comes back. It could happen to anyone. The police are called, you tell them your story, and nobody is to be found. What would you do? That is the dilemma Lucy Costigan’s Glenveagh Mystery sets out to explore. She has created a page-turning historical drama replete with maps and descriptive illustrations leading readers on a treasure hunt for clues to how someone can just vanish without a trace.

We find ourselves asking the same question that prompted Costigan to research and write this book. What happened on that fateful night on Inishbofin Island when the renowned art historian/millionaire Arthur Kingsley Porter vanished without a trace? The book unfolds in a way that allows us to assume nothing.

What we learn is that Porter was born into a well-to-do family in Darien, Connecticut. He lost his mother at a young age. Subsequently, his father had a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and he soon set about hiring a series of attractive young women to attend to his needs,

And yet, from an early age Porter felt himself to be a man shackled by social responsibility who wanted only to be free. His restless spirit constantly sought

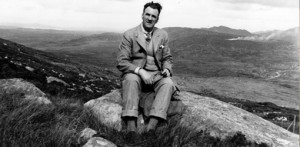

freedom through travel and exploration. He would become a noted American art historian and medievalist whose claim to fame rests upon his groundbreaking studies of Romanesque sculpture and Lombard architecture. Writing and refining his ideas, Porter drove himself relentlessly to finish his thousand-page study, Medieval Architecture: Its Origins and Development, which was completed in 1907. The book set the standard for a new generation of art historians.

Early in 1911, at a social gathering, Kingsley met his future wife Lucy Brian Wallace. He was a tall, shy, and handsome 28 and she a pleasantly plump 35-year-old with highly developed sensibilities who was immediately drawn to Porter. The fact that Lucy was seven years older did not deter Porter from proposing, and they were married at the home of her parents in June of 1912. Three years later, Porter was teaching at Yale, his alma mater, where his family had studied since the 1840s. In late January, he wrote to the president of Yale stating that he wished to leave a bequest to the university to establish a faculty of art history. Two years later, Porter was appointed assistant professor of art history at Yale.

Nine years later in the preface of a new book, he writes “that in all great art the intention of the artist must be to bring forth a creation from the depths of the soul, from the sublime well of emotion; for the essence of all great art is Joy: the joy of grandeur, the joy of poetry, the joy of gloom … but always joy. The genius endows the object with a spark of the divine joy, so that it may awaken the same or a kindred emotion.” Seeking “joy” became the driving force of his life.

After much persuasion, in 1920 Porter finally accepted an appointment at Harvard. At this time he was completing his landmark study Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads. But for all his devotion to the Middle Ages, he harbored an abiding love of Greek art that was not well understood during his life. He took particular delight in the nude male figure and was fascinated by the play of muscles that was “the glory of manhood” in Greek sculpture. What impressed him was the fact that the ancients had no shame about expressing their admiration for male beauty and “made of it a glorious hymn in praise of sex.”

At age 45, Porter had everything that most mortals could hope for, yet he grew increasingly restless and despondent. At the very height of his success, he began to experience serious bouts of depression. During this crisis, an inner secret that he had kept bottled up and hidden his whole life struggled to emerge, a secret that would shatter his private life forever.

He began to delve into his own sense of despair by studying psychoanalytical books and came to believe that the root of his unhappiness was his sexual repression. His growing insights led him to a painful confrontation with himself. He longed for a passionate sexual relationship with another man. The story of how he went about summoning the courage to tell Lucy about his homosexual fantasies and find his joy is fascinating. The fallout from his confession led him to seek treatment with the foremost sex therapist of his day, Havelock Ellis. Ellis was the co-author of the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality, Sexual Inversion (1897, co-authored with John Addington Symonds), which describes the sexual relations of homosexual males, including adult men with youths. Ellis did not classify homosexuality as a disease or a crime. His sympathetic discussion of Greek pederasty encouraged Porter to take a young male lover.

In July, Alan Campbell, a patient of Ellis’, arrived at Porter’s rental home. He stayed almost a week, during which time he and Porter became lovers. It was the beginning of a strange ménage à trois. By 1923, Alan was a part of the couple’s Cambridge life in the very heart of homophobic Harvard. Porter’s spirits soared; he displayed a new zest for teaching, and all seemed well with their world. But Campbell was not in love with Porter and missed his ex-boyfriend in California.

Afraid of being outed as a gay man at Harvard, Porter was constantly restless and itching to get away. On August 29, 1929, he tried to resign from his post, but his resignation wasn’t accepted. That same year, Porter bought the Glenveagh Castle (constructed 1870–1873, in County Donegal) where he and his wife Lucy would spend several months each year, learning Irish and studying archaeology and culture.

On July 8, 1933, while spending a night at the fisherman’s hut he had built on Inishbofin Island, Kingsley Porter disappeared without a trace. The subsequent inquest was the first to be held in Ireland without a body. Lucy told of frantically searching the outlet, desperately trying to locate her missing husband all through the day and well into the evening. She related that in the afternoon a thunderstorm developed, and the island’s rugged and rough beaches were strewn with boulders. Porter was presumed to have drowned, but the inquest was inconclusive.

Nothing was said about Porter’s homosexual tendencies. The mystery of what really happened to Kingsley Porter remains unsolved. Sightings of the professor continued to be reported from locations around the world for many years after his disappearance. People swore they saw him as far away as India. In October 1933, Lucy set about establishing a scientific fellowship for research into homosexuality. She mentions corresponding with Alan in a letter to Dr. Ellis, with whom she kept in touch after her husband’s disappearance.

Glenveagh Mystery takes us on an intriguing hike down a series of twisting paths that veer off into the brambles. In a narrative studded with cultural, moral, and psychological thorns, Costigan gets at the core values of her characters. The book ends with the various rumors that followed Kingsley Porter’s disappearance and implies that he and Lucy may have staged his death so that he could start a new and joyful life as a homosexual. She leaves readers with two questions: Did Kingsley row or swim to the mainland from the island before the storm? Could he have continued his studies and travels as the medieval pilgrim he had always yearned to be, leaving behind a life that he no longer found tenable?

What we do know from reading Costigan’s thriller is that Porter was an intrepid traveler who had explored the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia, and who felt at home almost anywhere he went. In an era when no identification was required of a foreign gentleman traveling, starting a new life would have been easy. Kingsley could have gone anywhere in the world to live out his dream of a joyful (gay) life.

Cassandra Langer, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a freelance writer based in New York City.