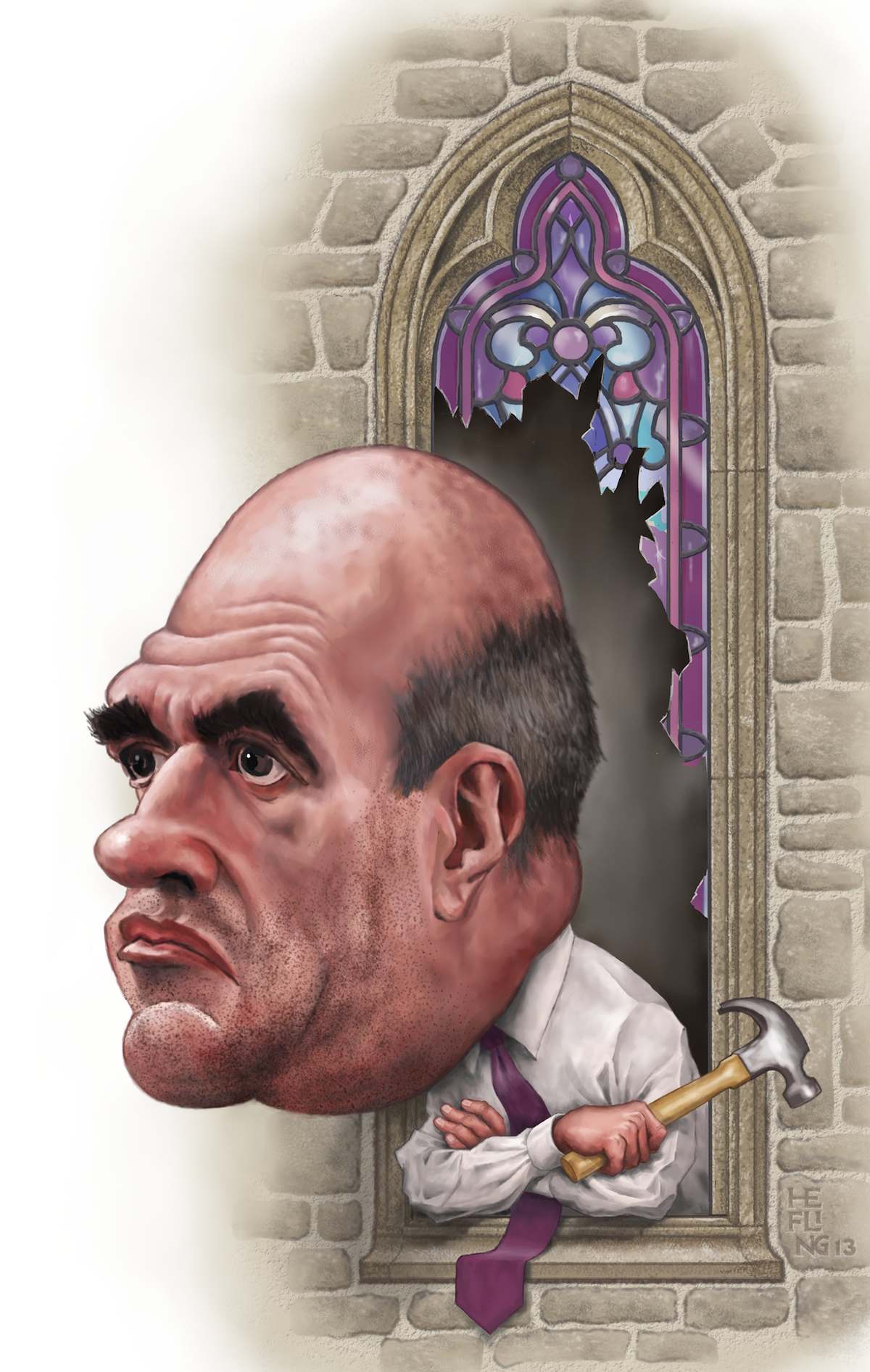

Irish essayist, playwright, journalist, critic, and former altar boy Colm Tóibín chalked up another milestone when his one-woman play The Testament of Mary opened on Broadway last April. while its run was short, the play was nominated for a Tony in the Best New play category. The Testament of Mary is based on his 2012 novel and imagines the untold story of the Virgin years after the disappearance of Jesus.

Tóibín’s prose style has been described as “daring and precise,” “austere,” “lyrical,” “reticent,” and even “monkish.” The New York Times named his award-winning 2004 novel The Master, which is based on the life and career of Henry James, as one of the ten most notable books of the year, and it was short-listed for the Booker prize, as was 1999’s The Blackwater Lightship. His novel The Story of the Night (1996) won the Ferro-Grumley prize. His 2007 short story collection Mothers and Sons displays the full range of his ability as a prose stylist, as does his noirish tale The Use of Reason, about an art thief trapped in a dead-end situation. And there’s the existential mood of A Long Winter, which recounts a young gay man’s desperate search for his runaway mother in the snowy pyrenees.

Tóibín lives part-time in Manhattan in a twelfth floor sublet apartment on riverside drive, a block away from Columbia, where he is the Irene and Sidney B. Silverman professor of the Humanities, and where this interview was conducted.

Michael Ehrhardt: Catholic protesters picketed the theater during previews of The Testament of Mary, chanting rosaries and bearing signs labeling the play blasphemous. you were even compared to Satan. Did that come as a surprise to you?

Michael Ehrhardt: Catholic protesters picketed the theater during previews of The Testament of Mary, chanting rosaries and bearing signs labeling the play blasphemous. you were even compared to Satan. Did that come as a surprise to you?

Colm Tóibín: Actually, there were very, very few protesters. I think there were about fifty at a preview, and about a little over a hundred at opening night. Whereas between 30- and 35,000 people saw the play. Nobody in the theater ever protested or stood up to say this could not go on. This was a highly organ- ized protest. It’s a free country, after all, and people have a right to free speech.

ME: Testament was first performed in the Dublin Theatre Fes- tival in 2011. Did you feel particularly vulnerable as a gay man publically challenging the Church in Ireland? Were there pro- testers there too?

CT: Not at all! It was quite the opposite. There was a mecha- nism in place whereby if someone wanted to leave the theater during a performance, they could. We had it controlled that way. And nobody ever did leave. It was a smaller theater, and so there was much more tension. But it was a theatrical ten- sion. No issue arose, either inside or outside the theater about my sexuality or the contents of the play.

ME: You said somewhere that you believe the concept of the closet is slowly dying from American life. What about Ireland?

CT: Things have always been different in Ireland from the U.S. There are different degrees to being out there. you find people who are out to their family, but not to their grandmother, out to their mother, but not their father, out to their sisters, but not their brothers. It’s a gradual process. But you never find any- one totally in the closet nowadays, or it’s very unusual.

ME: As a recipient of many accolades and awards for your writing, what’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word “shortlisted”?

CT: About the Booker Prize, I don’t use the term shortlisted, I use the word “lost.” That I lost it twice.

ME: What do you think when you’re referred to as a “writer’s writer”?

CT: Oh, I love that idea! But, you know, John Ashbery de- scribed his condition as a writer’s writer’s writer. That’s one better. Because only a writer’s writer can read you. I mean, I’d like to be a writer’s writer, but every so often I write a book in which other people can participate.

ME: you live part time in Dublin, Spain, and New york. Have you become adept at dealing with culture clash over time? Does it have any impact on your writing?

CT: I don’t really think so. When you get to a certain age you live in your head, rather than on the street. And because I’m up here [in northern Manhattan], so far away from “New york”—I mean, I don’t even get a train card and go down into it. This is a very isolated spot. And when the wind blows in the winter off the river, you really realize that you’re not in a cozy city. So, I really live inside my head. It doesn’t really matter where you are when you’re writing, because you’re sum- moning up memories and working with ideas that you may have long ago mapped out, so that you’re looking down, and the page is not a mirror, so you’re not seeing anything. There- fore, where you are is the least relevant thing about writing. I can write anywhere.

ME: After university in Dublin, you travelled to Barcelona, then Argentina, the Sudan and Egypt. The doyenne of Irish literature, Edna O’Brien, says that “writers are always on the run.” Can you relate to that?

CT: I think Edna O’Brien came out of a particularly bad time in Ireland, and suffered accordingly, but she really spent most of her life in London. I think she would have found Ireland an impossible place to be for someone like her, a feminist with such a large ambition. She wouldn’t be taken as seriously there as she was in London, as a stylist or somebody whose books ex- plored very difficult matters.

ME: Can you really teach the mechanics of writing? And what advice do you give young writers?

CT: Well, you can create a safe place where people can become very serious about their work and what they’re doing. And if you’re lucky, you have some people who are very talented— and there’s actually nothing you can do for them. I mean, among the students I have had was Philipp Meyer, who wrote American rust, but I don’t think he really learned anything from me. But there was something that might have made him feel that this sort of work was important, so that coming in once a week and having me there might have made a difference to him. But not a big difference.

ME: You’ve said that “you have to be a terrible monster to write.” Quote: “Someone might have told you something they shouldn’t have told you, and you have to be prepared to use it because it will make a great story. you have to use it even though the person is identifiable. If you can’t do it, then writ- ing isn’t for you.”

CT: Be careful when you’re around a writer.

ME: You’ve written about your early adulthood living in Ire- land, when the laws against homosexuality were still on the statute books (as they were until the early 1990s). How were gay connections formed in such a repressive environment?

CT: It’s a very complicated Irish story. For the most part, with certain exceptions (the late ’60s), the police ceased to be inter- ested in that law. When, for example, an effort was made in the European courts to declare the law [to be]against the conven- tion of human rights, our government said, “We don’t even use the law, haven’t used it for years.” And that was true. The dif- ference between London and Dublin in the years after the de- criminalization in London was that Dublin was a smaller city, and a more intimate place, and people were much more afraid of coming out, of losing their jobs or their connections with their families. There were many relationships of people that I know that started in those years who are still together, who’ve lived together without any difficulty at all from the state. The problem was always about visibility and fear. There was no de- bate about it; it wasn’t on the radio or television or on film—it wasn’t there! yet, as a gay man I was riled upon hearing a car- dinal, otherwise a reasonable man, come on the radio scream- ing about the need to imprison people like me!

ME: The filmmaker John Waters, who went to a Roman Catholic high school, has stated: “Thank God I was raised a Catholic—so sex will always be dirty.” you wrote in The New York Times about how your spiritual crisis was compounded by revelations about sexual abuse by priests. This is a source of your story “A Priest in the Family.” Were you aware of such abuse while you were in Catholic school?

CT: No, absolutely not. However, lots of other people around me knew of the abuse of boys. I mean, there was one priest who was mentioned, but it was taken as sort of a joke. Nobody ever took it seriously. However, I never knew it—which is strange, not to know something that must have been right in front of my nose.

ME: You helped serve Mass as an altar boy in Dublin. And you once actually thought about becoming a priest? What was the appeal for you?

CT: I think one of the reasons why is that being a gay teenager involves a great deal of introspection, so you move inwards rather than outwards. And, instead of having a natural way of handling the world out there, that becomes a way that you in- vent, and nothing is taken for granted within the self. And that can hit at a spiritual space within the self, and it can hit a cause, and suddenly the two things merge, that actually are very un- like each other, yet both are entirely about the inner sanctum of the self. And that has always to be kept so private, that many things can happen with it, and all of that can arrive at the point of a very deep spirituality. I think that’s something a lot of gay men may recognize, but not find it particularly easy to talk about. It might come up in the writing of James Baldwin, for example. That might be where I noticed it the most.

The other issues were, I suppose, that becoming a priest would allow you to function within society, as someone who could be a leader, who could be very useful, could be needed. That could be something very beautiful to be needed. And that must have been a very attractive image for me as a boy.

ME: You say that reading between the lines for gay connota- tions and validation was part of your literary growth, if not a technique for survival. What was some of your formative reading?

CT: I read Hemingway. I mean there were different phases of Hemingway, so you can choose them, as opposed to his over- blown masculinity, which I didn’t identify with. Henry James, and Fitzgerald, and Kafka, whom I found very exotic. I cer- tainly read William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch by the time I was seventeen or nineteen. And James Baldwin’s Go Tell it on the Mountain and Giovanni’s room, which seemed to have more that I could relate to. I read Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge and his gay novel The City and the pillar, which I didn’t think was very good.

ME: Anglo-Irish writer Elizabeth Bowen’s work is full of char- acters, usually coded, who are either clearly or ambiguously homosexual. Iris Murdoch, also Irish, has openly queer char- acters, some of whom are more likable than her straight ones. Did either of them have an influence on you?

CT: I read a lot more Murdoch than I did of Bowen. I read Murdoch’s books in waves when I was in my twenties, and I think she must have had around nine or so books by then, and I think I read them all. I only met her soon after she became ill.

ME: Your fascination with Henry James and appreciation of his work led you to write The Master, but while you admire his work, you believe that he wasn’t master of his personal life, “a life of pure coldness,” you say, due to his closeted existence.

CT: I believe that James actually gained a lot by being clos- eted, in the sense that he worked harder than he might have oth- erwise. It’s hard to imagine how he might have done anything differently than what he did. The interesting figure is not al- ways Oscar Wilde, but instead it can be Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), who was an English socialist philosopher and early gay activist, who lived a mostly openly gay life. He spoke to clubs about socialism and about sexuality and certainly had many lovers. What’s interesting about him is that while Wilde went looking for trouble, Carpenter did not. There was a kind of odd sincerity about Carpenter, which made people leave him alone. So, it wouldn’t have been impossible for James to live openly, especially if he stayed in Paris or Rome. But he didn’t. I think it began to affect him deeply when he was in his fifties, but not so much twenty years before that. So, from about 1875 to 1895, James had been quite content.

ME: Why was Henry James so important to you to take on as a character?

CT: I suppose the primary thing is that there really isn’t any- one else like him as a novelist. I mean, the size and ambition of his body of work, and then the prefaces, essays, and short sto- ries he wrote, make him a towering figure for anyone interestedin the invention of character, especially the nuanced expression of character. And he remains that: a pure artist. I had originally had no interest in him personally, other than his work. But still, I was intrigued enough to go and find out more about him. And I was very taken with the way in which his self fed into the work—or didn’t—the artistry of both the barrier and the re- lease mechanism. I became interested in how James had navi- gated the particular waters not only of his sexuality but also of his talent. And I was interested in the palpable absence of the author in the books, the artist keeping himself at bay. And there’s a lesson for us all in relation to his seriousness, for ex- ample, or his industry. The other matters, of course, are sad. It might have been better had he been rewarded in his love life and his home life with some measure of happiness.

ME: You don’t mention Edith Wharton in The Master. She and James started as pen pals, then were friends and traveling com- panions. She must have been a close confidant as well. Why did you leave her out of the novel?

CT: Edith Wharton first met James in the late 1880s, but their relationship didn’t really flourish until after 1900. And my novel ends at the turn of the century. And I think their rela- tionship was so easy to understand; there was no mystery around it.

ME: Do you suppose James ever confided his sexuality to her?

CT: No. However, she knew everything. I mean she lived in Paris for so long and met everyone. She would enter a room and take one look around the room, and—trust me. In addition, they were both in love with the same man, William Morton Fullerton, which she certainly knew about just by observing James.

ME: Do you think that Henry James (unlike George Bernard Shaw and Frank Harris) refused to sign a petition to free Oscar Wilde out of fear of having his own reputation tainted by the scandal?

CT: Well, James really did dislike Wilde and found his work of no interest. He found his work silly, and he found his flaunting around London silly. James was thoughtful, many-sided; he lis- tened very carefully, was very clever, but he saw Wilde as a big camp. The Wilde affair was a different matter, and it intrigued him. But he certainly wasn’t going to put himself out in any way. And it wasn’t just about signing a petition, because he did- n’t sign any other petitions; he just wasn’t a petition signer by habit. George Bernard Shaw, being a socialist, was almost pro- fessionally involved in signing petitions.

ME: Wilde was a walking paradox. Do you think it is possible that subconsciously, perversely, instead of leaving the country, he wanted his love affair with Bosie to be made public?

CT: Yes, I do. I think that the secret history of it all is that, somehow or other, he wanted it to be known. It makes no sense otherwise. His suing of the Marquess of Queensberry makes no sense otherwise. Often, he was behaving like a total fool. But there was some funny part of him that he wasn’t even aware of himself: that wanted society to know his secret. Just the idea of being publicly represented, known, and validated. I’ve written about this need in heterosexual relationships as well. For instance, in The empty Family there’s a lead story called “Silence” in which Lady Gregory has a torrid affair, and no one ever knows about it. And afterward, because it was se- cret and untold, she suddenly feels that the whole thing was somehow unreal, that without having a confidant or friend to talk to about the fact, it not only reduces the emotion, it actu- ally crumbles the affair, and it ceases to be.

ME: There’s a similar theme in your earlier novel The Story of the Night, when the protagonist, Richard, begins his clandestine affair with young Pablo and gradually feels it doesn’t fully exist unless recognized by family and other people, and aired out in the sun.

CT: Yes, I must have remembered that when I wrote “Silence.” It does seem that in our relationship to society it is somehow re- quired, though it really shouldn’t be. If you think about it, it re- ally doesn’t make sense.

ME: The daily dilemma for gay men is that we’re always on the defensive; placed in a ridiculous position in which we con- stantly have to defend our very existence in a hostile hetero- centric society dominated by a willful blindness to our basic civil rights.

CT: I think that when the gay rights movement began here, and, I think, it made its way through feminism into the gay world, it was a hugely liberating force. I remember once, being out with a friend in a coffee bar and talking to a nice old gay man, who suddenly said to us: “Look, you’re young. The most important thing for you in your life, and you may not think this is true, but the most important thing is to be nice to your boyfriend.” I was very moved, because there it was: if you couldn’t keep the private part of your sexuality, then all your ef- forts to do the public thing were for what?

ME: Back in 1993, you refused a commission from The Lon- don review of Books to write about your homosexuality, and you replied that you couldn’t do that, explaining that your sex- uality “was something that remained uneasy, timid and melan- choly, and had nothing polemical and personal, or even long and serious to say on the subject.” Is that still true today?

CT: Well, I didn’t want to write an autobiography, or about how I’m a poor victim of Irish Catholicism. And I also didn’t want to be in the front line of any sort of march, because I felt there were politicians and activists out there who could do a better job than I could. But also I realized that whatever I was going to do, I was going to find metaphors for it—ways of deal- ing with it by finding characters whose lives I can dramatize in ways that I could not dramatize my own. And I would never really be able to make sense of myself. There’s no character in any of the books that I can tell you: that’s me.

ME: You’ve admitted in an interview in Bookslut that you have personal demons, “suffered certain hurts in childhood,” and you go to a shrink to deal with them. What do you consider your demons? Are they an intrinsic part of what makes you a writer?

CT: Well, I don’t know about the second part of that, because you can never really tell why you pick up a pen. And people who may have been through similar experiences did not. However, when I was eight years old, my father had a very serious brain operation, which made it hard to understand him when he spoke—although I would try—so every conversation with him was very difficult. He lived on for four more years, and he died when I was twelve. And all those issues surrounding ado- lescence, puberty, and sexuality became extremely strained, be- cause I was dealing with this all by myself. It wasn’t as if there was any help for it. So, those things got twisted around each other, and I moved into an area of very great defenses and of privacy. Even what I’m saying to you now took a very long time to accomplish. All of that has fed into the work. There’s nothing I can do about that; it just comes up on its own.

ME: Your novel The Story of the Night was the first to deal fully with homosexuality. The young protagonist, Richard, who covertly puts on his mother’s clothing, is a poignant encapsu- lation of someone experimenting with sexual identity. Like yours, his father—also a schoolteacher—died when he was twelve. It’s all in the first person. Is that novel semi-autobio- graphical?

CT: Oh, no. I mean it’s a different historical background, and he’s Argentine. I selected a voice for him, and I kept trying to give him images that I thought would be true. I myself had sib- lings and was brought up in Ireland. As a professional journal- ist, I was always on the go, ready for the next thing. That character is much more helpless, isolated, and vulnerable than I’ve ever been.

ME: AIDS is a big plot element in Story of the Night. To what extent were you personally touched by the epidemic?

CT: When AIDS arrived in Ireland, it was an absolute disaster, because the fact of being gay was not ever mentioned. It was a situation in which people—and I knew many of them—in the same night had to tell their parents that they were a) gay, and b) dying of AIDS. Their parents were worried about the neigh- bors and what was in the papers, what it would look like to the outside world. Even on an intimate level, this affected large families in small towns, and it all took on an element of almost unbearable pain. All this, besides the actual impact of the illness itself. Then one of my closest friends died. When I spent a lot of time in London, in the late ’80s, it was shattering; everyone had a friend or lover who was sick or dying. It became part of daily life for me.

ME: You’ve written many essays on art and artists, and you’re quite a museum-goer. you once said that if you could own any painting it would be Titian’s Man with a Glove, which hangs in the Louvre. It’s also on the cover of the UK edition of The Story of Night. Did you choose it yourself?

CT: Oh, yes, I did. I suggested it to the publisher. The strange part is that George Eliot imagined that very portrait to be Daniel Deronda [hero of her eponymous 1876 novel]. Luckily, we were able to get the rights to reproduce it, because I thought it would be counter-intuitive and not obvious, and provocative.

ME: What fascinates you about the picture?

CT: Oh, it’s an extraordinary piece of work! And there’s some- thing vulnerable in the eyes and especially in the intense glance, with that tinge of melancholy.

Michael Ehrhardt is a freelance writer based in New York City and Roseland, NJ.