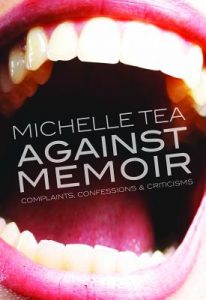

Against Memoir: Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms

Against Memoir: Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms

by Michelle Tea

Feminist Press. 318 pages, $18.95

THE EARLY DAYS of lesbian-feminist literature boasted authors with big personalities—Rita Mae Brown, Germaine Greer, Kate Millet, and Jill Johnston, to name but a few. Since then, the field has been largely bereft of such outsize figures. True, there are many terrific mystery, science fiction, fantasy, and romance novelists, lesbian and bisexual professionals who have lots of loyal supporters. For this reason, if Michelle Tea didn’t already exist, she would have to be invented.

Luckily, she does exist, and she’s made a name for herself with books like Valencia, Rent Girl, and Black Wave, as well as books about the Tarot, various anthologies, and performance pieces through the group Sister Spit. For most of the 1990s and early 2000s she was the spokesperson for a generation of San Franciscans, detailing the residential, literary, and intellectual changes and challenges of the city. She was also the force and soul behind the radar reading series that kept LGBT literature alive in the Bay Area. Now in her forties, she is married and a mother and living in L.A.

By the end of the book we feel we’ve come to know Tea as well as we know the author of a more standard memoir. In her homage to Times Square, Tea writes of her younger self: “I wanted do writing, making music, maybe becoming an artist, maybe I already was an artist, but I would never learn this about myself in smoky, sad, racist Chelsea, Massachusetts. I would have to go to a city to become an artist, to become myself.” Tea understands hyper-logorrhea, the need to write it all out, to get it all down, no matter the topic under consideration. It’s a cool method, so casual you almost don’t see it happening. Given her friendly “out there” social attitude with no apparent agenda, this is possibly the best way to write a memoir—or anti-memoir.

We get vivid pictures of her life and times, as well as where Tea was mentally at each time and place. She’s not afraid of opinions. Regarding those famous Womyn’s Music Festivals, in “Transmissions from Camp Trans,” she writes: “the real purpose is to hunker down in a forest with a few thousand other females, bond, have sex in a fern grove, and go to countless workshops on everything from sexual esoterica to parading around on stilts, processing oppressions, and sharing how much you miss your cat.” In her essay “How Not to be A Queer Douchebag,” she commands: “Stop policing each other like little queer police officers. I have never seen a quadrant of people so ready to tear each other’s faces off as queers.”

As to why she titled her book as she did, Tea explains it in several essays. In “Polishness” she concludes: “Anyone would get sick and tired of doing the same thing for seventeen years. When a memoir is what you’ve been doing. It means you’ve become horribly sick of yourself, of your narrative, and I had.” Tea may have turned against memoir as a genre, but those years writing one were certainly not wasted.

________________________________________________________

Felice Picano’s latest book is a memoir titled Nights at Rizzoli.