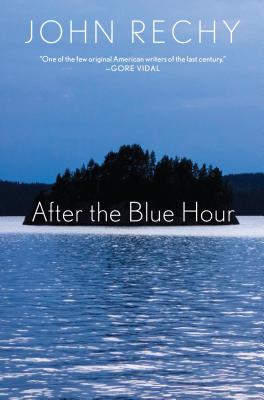

After the Blue Hour

After the Blue Hour

John Rechy

Grove Press. 212 pages, $25.

IF ALL YOU KNOW of John Rechy’s work is City of Night or Numbers or Rushes, be advised that his later novels, such as Marilyn’s Daughter (1988), The Miraculous Day of Amalia Gomez (1991), and even The Life and Adventures of Lyle Clemens (2003), are not only worth reading but far more entertaining on different levels than many popular novels by much younger writers. For those who clamor for a more “gay-themed” book from Rechy than the above, his latest novel, After the Blue Hour, ought to be the answer.

The French have a name for this kind of book: a “récit.” Examples are Camus’ The Stranger and The Fall, several of Gide’s shorter works, and many novels by recent Nobel Prize-winner Patrick Modiano. The author consciously limits the scope and length of the work and by doing so achieves a compression and intensity difficult to get with a longer work. The cast of characters is also limited, and there is generally a shorter set time of action. In addition, Rechy’s récits could be considered postmodern in that he is self- consciously playing with the idea of form and genre.

The protagonist, the young “John Rechy”—placed in quotation marks when I mean the character in the novel—is a writer who has published several excerpts of what will become his first, breakout novel. One character even calls him by his full name every time he addresses him lest we forget who’s narrating the novel. So, is it autobiographical, or is it in fact a memoir? Who can say? It’s a sort of mixture of other European types of fiction, such as the “idea novel,” whose closest cousins might be Gert Hofmann’s Auf dem Turm or Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kröger. Then again, it could be a Bildungsroman. Or a garden party book. The sand beneath the reader’s feet is always shifting.

As it does for the narrator himself, unsurprisingly. The young author, who works as a hustler, has been invited by Paul, a very wealthy, somewhat older, physically attractive man, to spend the summer months on his private island. Present are Paul, his beautiful younger consort Sonya, and his teenage son Constantine. The only others are a pair of servants, male and female, so unremarkable that he calls them the Gray Ones. This could be a perfect setup for a writer to get some work done. There are virtually no rules. Everyone seems free to go off and do whatever he or she wishes. But there are unspoken requirements too. For example, Paul tells “John Rechy” about his two marriages in sensually excruciating detail, explaining how and why they ended. But he got richer and richer with each divorce, the island being one acquisition. “John Rechy” naturally wonders how he’s supposed to respond, so he tells some of his own sex stories, in effect matching Paul’s escapades. But, unlike Paul, he is completely objective about his sexual adventures: it’s just a job. Anyway, he comes not to like Paul much, and doesn’t like Paul’s son at all, but he begins to like the seductive Sonya very much indeed. More sand shifts under his feet.

As it does for the narrator himself, unsurprisingly. The young author, who works as a hustler, has been invited by Paul, a very wealthy, somewhat older, physically attractive man, to spend the summer months on his private island. Present are Paul, his beautiful younger consort Sonya, and his teenage son Constantine. The only others are a pair of servants, male and female, so unremarkable that he calls them the Gray Ones. This could be a perfect setup for a writer to get some work done. There are virtually no rules. Everyone seems free to go off and do whatever he or she wishes. But there are unspoken requirements too. For example, Paul tells “John Rechy” about his two marriages in sensually excruciating detail, explaining how and why they ended. But he got richer and richer with each divorce, the island being one acquisition. “John Rechy” naturally wonders how he’s supposed to respond, so he tells some of his own sex stories, in effect matching Paul’s escapades. But, unlike Paul, he is completely objective about his sexual adventures: it’s just a job. Anyway, he comes not to like Paul much, and doesn’t like Paul’s son at all, but he begins to like the seductive Sonya very much indeed. More sand shifts under his feet.

There are moments of great poetic beauty here, but there’s also an obviously highlighted treatise about evil in the library, and lots of little moments presaging something like doom. As for “John Rechy,” he can’t swim, a distinct disadvantage on an island, but he learns to handle a rowboat and eventually becomes waterborne. This allows him to spend time with Sonya and to investigate the mysteriously mist-covered island nearby with its half-charred single house, the subject of many lurid stories that the son has heard from the locals.

Eventually, tensions rise, Paul manipulates the adults into a not quite embarrassing sexual situation, and the teenager acts out on his own. Is it all “a game,” as Sonya cautions? Of course, the three are all playing different games: the boy one of love and death; Paul a game of getting “John Rechy” to do what he wants; and Sonya a game in which everyone admires her as much as possible, before the likelihood of her being dumped for another woman. As in all Bildungsromans since Goethe, our narrator walks away a little wiser and with his scruples, if not his honor, intact. But there are enough questions remaining about what actually happened on that island for him to write this book.

What John Rechy the author is telling us is that there are times and places in even a controlled, well-considered life that may stand out for us in memory, not necessarily because we did anything wrong or bad, but because some element in their inexplicability almost eradicates whatever else we recall. We may never know, even if more facts are produced. That’s a truth that someone who has lived as long and thought as hard as Rechy can assert with authority.

Felice Picano’s latest book is a memoir, Nights at Rizzoli (OR Books).