THIS IS the unspoken story of the extraordinary relationship between John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), the preeminent portrait artist of high society of his era, and his African-American muse, Thomas McKeller.

Born in Florence to American parents, Sargent lived mostly in Europe but he kept strong ties to the U.S., mainly Boston. He was an obsessively private man, never married, gave no interviews, and didn’t keep a diary or write an autobiography. If he was gay, he certainly couldn’t be open about it. A “confirmed bachelor” like his close friend Henry James, Sargent was Oscar Wilde’s neighbor for a time and lived under the shadow of Wilde’s trials, which established the emergence of the homosexual identity, closely associated with artists, and new laws that broadened the criminalization of gay activities.

Sargent navigated his public persona as a shrewd pas de deux between revealing and concealing. His secret life started cracking when dozens of intimate, sensual, voyeuristic, and openly homoerotic male nude drawings surfaced after his death. However, the first reference to his possible homosexuality didn’t appear in print until 1981.

Four years ago, a curator at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum accidentally discovered nine signed charcoal studies by Sargent featuring stunning images of an African-American model, Thomas McKeller (1890–1962). This discovery led to last year’s landmark exhibition Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent at this museum. We’re familiar with Sargent’s astonishing portraits, such as the iconic Madame X, but the central piece of this exhibition, a shocking nude portrait of McKeller, turned the perception of Sargent held by most museumgoers upside down.

In 1916, exhausted from being typecast as the portrait painter to the elites, Sargent embraced a new career when he accepted a major commission from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts to paint the murals for its rotunda and grand staircase. These murals catapulted Sargent from the private to the public arena and allowed him to create classical, religious, and mythological images, the perfect excuse to portray sensual male nudes, as Michelangelo had done in the Sistine Chapel.

Sargent, who was sixty at the time, noticed Thomas McKeller, a hunky 26-year-old African-American elevator operator at his swanky hotel. Sargent told him that “his physique would have artistic value” and asked him to become his model, which McKeller did until Sargent’s death a decade later.

There are no known photographs of McKeller, but we know that he posed nude for Sargent, who transformed him into alabaster-white gods and goddesses for his murals. He modeled for Eros, Ganymede, and a curly, blond-haired Apollo. As the exhibition catalog indicates, McKeller’s race was erased throughout Sargent’s murals. However, in many of them, Sargent featured McKeller’s irregular left nipple, making him completely identifiable.

A relationship between a famous white artist and a Black model was a radical idea, particularly in Boston, where discrimination (if not segregation) was commonplace. McKeller also ran errands for Sargent, and on one occasion he carried Isabella Stewart Gardner in his arms to the artist’s studio when the elevator broke down. Sargent wrote to his agent: “Let the darkey [sic]model know that I want him. I don’t know what I shall do without him.” The thorny racial dynamics between artist and sitter were complicated by the fact that, while McKeller was the source of much of Sargent’s inspiration, he received only a few dollars a day, while Sargent got paid $40,000 for the murals, a huge amount at the time. McKeller even modeled for the body of a Harvard University president who expelled black students from its dorms.

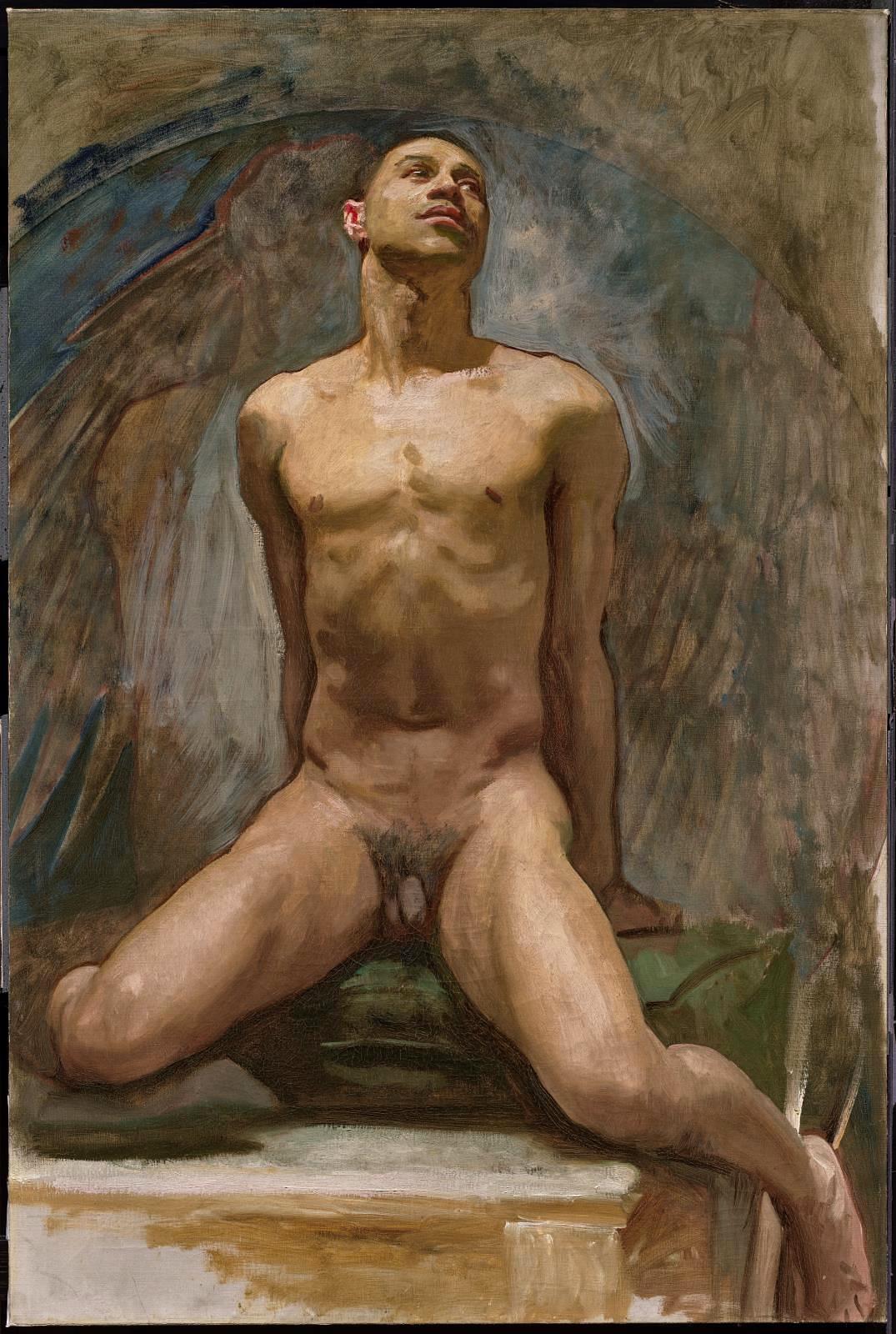

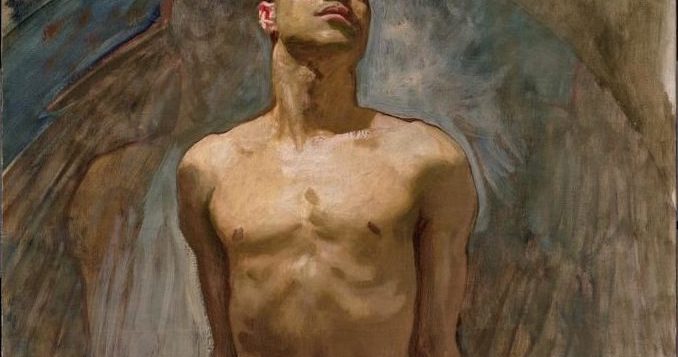

At some point while working on the murals, Sargent painted a ravishing, provocative portrait of McKeller. In it, he appears completely nude, sitting on a cushion, with a striking pose (he was a part-time contortionist), legs spread wide, his genitals a focal point, and his hands, apparently bound behind his back. Sargent lovingly illuminates McKeller’s golden brown skin, his muscles, and his Adam’s apple, and captures his tilted head in a moment of ecstasy. This is no quick or casual portrait, and it’s too large and polished to be a study. Sargent experts indicate that what makes it even more striking is that the image has no mythical or narrative justification. It doesn’t relate to any of the murals, and he painted it at a time when he was rejecting portrait commissions.

Sargent’s only major nude, and one of the great portraits of his career, the painting would have caused a scandal had the model been white. Having a black model gave it an “exoticism” that made it tolerable. Despite being one of

Sargent’s most poignant and beautiful works, he never exhibited it publicly, but proudly displayed it in his studio until his death, when his sisters decided not to keep it in their estate. The painting remained away from the public eye until Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts acquired it in 1986.

One of Sargent’s leading scholars, Trevor Fairbrother, has said that this painting confirmed his sense that Sargent was gay. He adds: “The conflict between Sargent’s public career and his repressed sexuality provides the key tension in his art, and gives us more insight into his work than the ‘asexual bachelor married to his work’ label used by many biographers.” If we believe the statements from some of Sargent’s sitters, he was attracted to men of ethnicities different from his own, with a predilection for Venetian gondoliers, who were famous for attending to tourists’ sexual requests. The painter Jacques-Émile Blanche declared that “Sargent’s gay sex life in Paris and Venice was positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger.”

Records show that McKeller got married and had no children. In a recent interview, his great-niece suggests that McKeller was suspected of being gay, and that’s why he left his native Wilmington, N.C., a city with an African-American majority, and moved to Boston. “To be gay was taboo,” she says, “even within your own family.”

McKeller didn’t attend the unveiling of the murals he inspired, presumably because the color of his skin might have precluded it. The day Sargent died, he paid his respects to Sargent’s agent and quietly went away. In his only known interview, Mc-

Keller proudly boasted that “the body in the Atlas mural was mine.”

We’ll never know if McKeller was just a model or if they had an intimate relationship, because Sargent’s letters and papers were destroyed by his family after his death. As there’s no written evidence of any same-sex relations, Sargent’s sexuality is debated to this day, but his art clearly tips the scales. The murals Orestes Pursued by the Furies and Hercules and the Hydra can easily be interpreted as a metaphor for his struggle with his homosexuality, and his tender portrait of McKeller will forever act as a deeply moving love letter to his muse.

Ignacio Darnaude, an art historian and film producer, is currently developing a docuseries titled “Hiding in plain sight: Breaking the Queer code in art.”

Discussion2 Comments

Whether Sargent was a homosexual since the term gay wasn’t in general use when he died does not really matter to me. He was a great realist artist. His interest in naked men and boys is not restricted to his fantastic painting of Mr.McKellor as shown on the cover of the G & L Review. The discovery of his watercolors of naked men only adds to our suspicion. The quote attributed to Jacques-Émile Blanche declaring that “Sargent’s gay sex life in Paris and Venice was positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger.” That is more than suggestive, if true.

Sargent is not alone as we wonder if the art of Thomas Eakins, Grand Wood, William Sorolla and Henry Scott Tuke suggests more than their canvases reveal. As Mr. Darnaude’s article suggests we will probably never know Sargent’s true desire but we have a chance to enjoy his fantastic art.

A persons sexuality is an important part of understanding who they are… In. a heterosexual dominate society the underlying assumption presumes that it is normal that desire is a motivating factor in how an artist perceives inspiration. And yet a homosexual orientation is dismissed as being non- essential to the artists creative genius. This is because being gay is still tainted in a negative way. You would not find a historian being uncomfortable claiming someone straight and yet they do cartwheels around obviously gay figure s by saying there is no solid evidence of gay sexual relations.