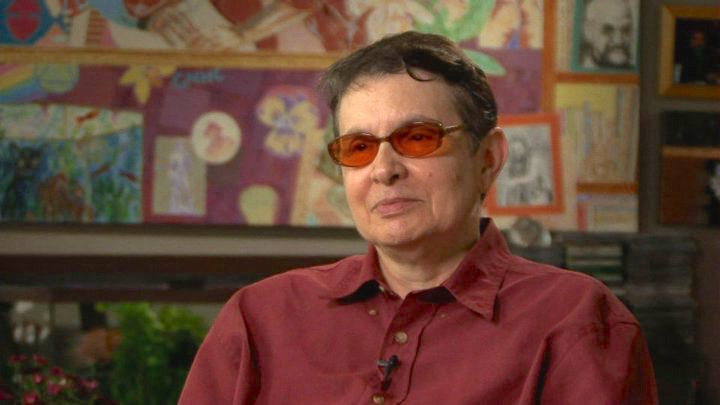

GAY AND LESBIAN READERS in the 1970s devoured After You’re Out (1975) and, years later, Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation (1992), books that Karla Jay co-edited with her close friend Allen Young. Younger generations have encountered Jay in She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, Mary Dore’s 2014 documentary about mid 20th-century feminism.

A Brooklyn native with a ribald sense of humor, Jay was originally labeled “slow” because she had trouble reading and writing. Once she got glasses, she soared intellectually and earned a bachelor’s degree in French from Barnard (Columbia) and a doctorate in comparative literature from NYU. After nearly forty years of teaching at Pace University, she is now Professor Emerita of English and Women’s and Gender Studies. Her other publications include the anthologies Lavender Culture, Lesbian Erotics (1978) and Dyke Life: A Celebration of the Lesbian Experience (1995), along with the thoroughly entertaining Tales of the Lavender Menace: A Memoir of Liberation (1999).

A Brooklyn native with a ribald sense of humor, Jay was originally labeled “slow” because she had trouble reading and writing. Once she got glasses, she soared intellectually and earned a bachelor’s degree in French from Barnard (Columbia) and a doctorate in comparative literature from NYU. After nearly forty years of teaching at Pace University, she is now Professor Emerita of English and Women’s and Gender Studies. Her other publications include the anthologies Lavender Culture, Lesbian Erotics (1978) and Dyke Life: A Celebration of the Lesbian Experience (1995), along with the thoroughly entertaining Tales of the Lavender Menace: A Memoir of Liberation (1999).

Jay lives the Upper West Side of Manhattan with her spouse, Karen F. Kerner, a retired physician, and her vigilant guide dog, a standard poodle named Duchess. With the living room shaded against the bright sunshine that bothers her eyes, she spoke about her formative influences and offered some wisdom to young LGBT activists.

Hilary Holladay: Where did you get your interest in literature? Was there someone in your family who loved poetry or was a big reader?

Karla Jay: My parents were not big readers. We had a set of the Encyclopedia Britannica, which was very old and had been inherited from someone. The only books that came in were Reader’s Digest Condensed Books. My parents never read The New York Times. My father would read the Daily News or the Mirror. The woman who took care of me, Nene—the only thing she read me were cartoons in the newspaper and the sports scores. She was a big fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and we used to listen to the Dodgers out on the terrace, where we could get reception.

I didn’t read at all as a child. I was visually impaired and didn’t know it. I’ve written a piece called “Dummy” about how I wound up in a class for what they called “slow learners,” children who were seen back then as mildly retarded. Lots of other kids in that class were delinquent, so they stuck us all in this sort of holding pen. [The teachers] finally realized I’d been faking the eye tests. I’d sit in this room with these other kids and they’d go ahead of me and read the spelling chart. I would just repeat what they said, but I couldn’t see it myself. Finally a teacher caught me. He had an “E” and he held it up, and he said, “Which way is it facing?” I heard the kid ahead of me say “E” but I didn’t know which way it was going. The teacher was holding it, you know, a different way. So they realized I couldn’t really see at all. Finally I got glasses, and they realized that I wasn’t stupid.

HH: In Tales of the Lavender Menace, you write about your mother’s mental illness and the difficulties of your childhood and young adulthood. There’s no sense of bitterness or

even reproach in this memoir. How did you learn to go beyond those emotions?

KJ: I think through feminism. I was very bitter about my mother, because I always took care of her. I was a caretaker from the time that I was a small child. And my brother, who stayed at home [after college], was a caretaker, because she got worse as she got older. When I left home, the family doctor told me: “Don’t look back. You have to get out of there.”

She didn’t tell me until I was in my late twenties or almost thirty that she’d been married before. She’d married a man she knew was going to die of rheumatic heart, and there was nothing they could do for it. I realized that she wasn’t born like this, and that forces had conspired to give her this unfortunate life before she knew me. Her own mother had been crazy and died in a mental hospital. She must have had this really terrible time of it. There were no drugs back then to help her. So, after college, I got very much into Buddhism, which is all about accepting the world that’s around us. Like losing my eyesight—it just is what it is. We all get parts to play in life, and what counts is how you play your hand.

HH: Tell me about your mentors and teachers in the women’s movement.

KJ: There were people who encouraged me to write, particularly Robin Morgan, and there were people in the movement who, just by their presence and what they’d done before me, encouraged me. For example, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon had done so much in the 1950s with the Daughters of Bilitis. That was really a great inspiration. They had been so out and had faced so much opposition with so much cheerfulness. They did it during the McCarthy Era when it was much harder than when I was in the Women’s Movement, and we were following on the coattails of the Civil Rights Movement.

HH: Looking at the Women’s Movement as it emerged in the mid- to late-20th century, which of its voices do you consider as the most influential and long-lasting?

KJ: Well, although I disagreed with her stance on lesbianism, no one can discount the importance of Betty Friedan. She had her flaws, but The Feminine Mystique was really groundbreaking. And Gloria Steinem is not only an important writer and thinker, but she really is one of the most gracious and kindest people I’ve ever met. She cofounded Ms. magazine and the Women’s Media Center and became a voice to motivate people to remain active in the cause. Another person who was a mentor to me was Barbara Deming, who was a pioneer in the peace movement and civil rights. Barbara taught me a lot about pacifism and forgiveness and never seeing people as your enemy. If you saw people as your enemy, they would always be your enemy. Barbara always kept her eye on the goal. I learned when people were angry at me to just let it go. I think it was the greatest lesson, because I didn’t fight with people in the movement—they were not the patriarchy.

HH: I’m curious about your career as a professor and mentor at Pace.

KJ: I started at Pace in 1974 as an adjunct and decided early on that because Out of the Closets had come out in 1972, I couldn’t live my life in the closet, couldn’t have this double existence—it was too late already. I became the adviser of the Stonewall Coalition, which kept coming and going as the group kept getting decertified by a hostile administration. One of the things that I found most discouraging as a lesbian academic was that, later on, when there were groups of gay academics, the gay men mentored and encouraged other men, but they didn’t encourage and mentor lesbians.

HH: Why not?

KJ: I think that they saw men as having more potential for valuable careers and perhaps because they just didn’t connect with lesbians. So I’ve always tried to mentor young lesbian scholars and all women scholars who have come to me for help. I think people have to mentor both men and women and not just a select few. I think we have to go out of our way to mentor minorities, to encourage people who are coming up to go on and have great careers. That’s the challenge: not to rest on our laurels. People don’t spend enough time helping other people come up after us.

HH: Do you have advice for young lgbtq activists who are going to the next frontier beyond same-sex marriage?

KJ: College students don’t realize that when they get out of college, they’re going to be discriminated against. Not everybody is going to think [being gay]is really cool. And I think that they have to keep fighting for women’s rights, for the rights of minorities, for the rights of lgbtq people, for all of these groups. Then they have to turn around and help other people. They have got to continue fighting for basic human rights for everybody.

Hilary Holladay is the author of Herbert Huncke: The Times Square Hustler Who Inspired Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation (Schaffner Press).