IN A RICHLY VARIED literary arc, Brad Gooch went from writing novels (Scary Kisses, The Golden Age of Promiscuity) to publishing authoritative biographies of three fascinating, complicated figures of 20th-century American art. His pivot into nonfiction began in 1993 with City Poet, about influential New York School poet Frank O’Hara, and continued with his Flannery O’Connor biography in 2009, a memoir in 2015, and a life of Rumi in 2017. His latest book, Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, is about the gay graffiti artist turned global celebrity who died of AIDS in 1990 at age 31.

Haring left his hometown in Pennsylvania for New York City in 1978 and discovered a heady scene that combined art, music, literature, nightclubs, sex, and drugs. Fueled by a prodigious output—Haring did more than 5,000 drawings on New York subway stations—and his distinctive imagery and bold line, his reputation soared. His friends included Madonna, Basquiat, and Warhol. By his mid-twenties Haring was exhibiting and selling in New York, Europe, and Japan. He threw himself into politics, especially AIDS activism.

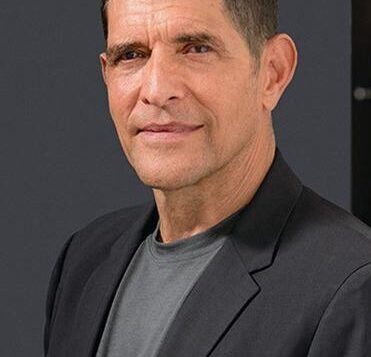

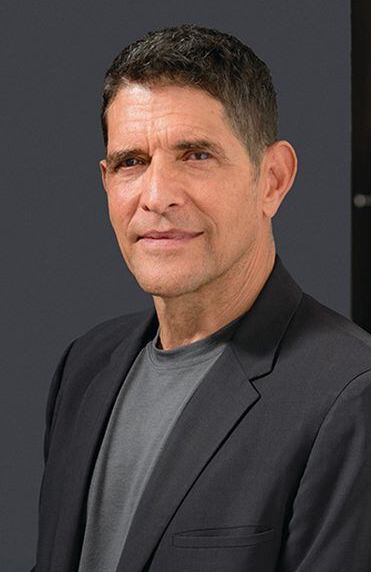

Gooch, 72, lives in New York City with his partner, Paul Raushenbush. They have two sons, Glenn and Walter. Gooch came to New York from Wilkes-Barre, PA, in 1971 to attend Columbia. He worked as a fashion model and has written for The New Republic, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and The Paris Review. A Guggenheim fellow in Biography, he has received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship.

This interview was conducted by telephone shortly before the release of Radiant.

Claude Peck: What led you to Keith Haring as a subject?

Brad Gooch: I was in New York City at around the same time as he was. He came in 1978. I crossed paths with his work on the streets leading from the West Village to the East Village, like some graffiti that said “Clones go home.” It was from this fake organization called Fags Against Facial Hair. In Soho I began to see his crawling babies on newsstands, and then the subway works. Supposedly he came to a book party that Dennis Cooper and I gave for ourselves at Limelight. I remember him at the opening of the Apollo Theater uptown, coming in with his fantastic posse of guys and girls. He was a scene-maker at that moment.

Later, when my lover Howard Brookner became ill with AIDS, Keith gave money for Howard’s care. I remember him at Howard’s funeral standing in the back looking sort of spooked because he was within a year of his own death. I always carried with me this idea to write a novel about Keith Haring. But the facts of Keith’s life are kind of astonishing … and the ten-year comet of his career hadn’t really been told in context. So it all came together to do this as a biography.

CP: With Flannery O’Connor (1925–64) and Frank O’Hara (1926–66) you wrote about writers born a generation before you. Was it easier writing about Haring, who was roughly your contemporary?

BG: It actually does make it easier. I had never been in that situation. With Frank O’Hara, I came to New York five years after he died. And it was not just that I was in New York when Haring was, but that I too was from Pennsylvania. So when I went to Kutztown [Haring’s hometown] and talked to his family, I really understood that family. They were very close. And yet at the same time, you had this funny matter that Keith never said the word gay to them. He never said the word AIDS to them.

And so you have the paradox of someone whose work stands for liberation, yet he wasn’t entirely, comfortably open with his parents. That was a kind of generational thing. I wrote these gay novels and poems and I would give them to my parents. And I had a lover who went home with me for Christmas and Thanksgiving and then came to my parents’ house in a wheelchair when he was dying of AIDS. And all of this was accepted, right? But it wasn’t exactly talked about.

CP: Knowing that Haring died so young somehow added weight to the details you recount of his childhood and early life. You have also written biographies of Frank O’Hara and Flannery O’Connor, both of whom died at a young age. Does a short life become a factor when you write a biography?

BG: Interesting. The three you mention were all also very driven by the idea of early death. Frank O’Hara was, for no obvious reason. Keith was also, and then it becomes verified with his AIDS diagnosis; and Flannery O’Connor had lupus. So they were all in a kind of overdrive and trying to pack a lot of life and work into a shorter time.

As for Keith’s early years, biographers kind of have to believe that Wordsworth line—“the child is father to the man,” that there’s this connection between childhood and one’s later years. With Keith, his Jesus Freak period, his love of the Monkees and his Grateful Deadhead period and his taking acid make a lot of sense in setting up the later Keith Haring. And his father, as an amateur cartoonist, had as much influence on him, as did Picasso and Walt Disney.

CP: There’s a big retrospective of Haring’s art that started at the Broad in Los Angeles in 2023 and is at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through September before going to Japan. And a major catalog. Are we having a “Keith Haring moment” in terms of his sometimes wobbly reputation among critics?

BG: It’s interesting to see Keith’s work now in a museum like the Broad. You realize his work is ready for renewal and reappraisal. The work definitely is trying to speak to us and has this kind of fresh surface to it, like it could have been done last night.

CP: It was still early in your writing career when you went from fiction to biography. Why the switch?

BG: I guess I was seduced by biography. I probably have a certain amount of genre ADD. I’ve done short stories, novels, memoirs. What’s satisfying and thrilling about biography is that it’s this kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, like a 19th-century novel in that it can go from birth to death and has this narrative pull. That’s something that I really like about it. I always see biographies as novels.

CP: Novels with a ton of research. You interviewed 200 people for the Keith Haring book, for example, and spent six years on it.

BG: Yeah, I talked to Edmund White about biographies. His thing is, it’s just too much work. I don’t think he’ll be doing another one again or any time soon. Biographers are always kind of self-deprecatory about the amount of labor that goes into this and the sort of limited ego of it, because you’re dealing with this figure other than yourself. I do all the research myself. I can’t say I enjoy footnotes and so on, but I do like the thrill of facts, pinning things down to actual reportage. You have to have a vision of it that connects to literature.

CP: How did you choose Frank O’Hara as the subject of your first biography?

BG: Frank O’Hara was like half in my world. There were a few reasons that I came to write that book, which seemed like a head scratcher to people when I started it—I mean, biography wasn’t a respected form at all in the ’80s. Frank O’Hara wasn’t really well known as a poet, and poets weren’t that valued. But I studied with [fellow New York School poet]Kenneth Koch at Columbia. And I had fallen in luckily to this crowd that included John Ashbery. And then my first boyfriend was J. J. Mitchell, who had been Frank’s last boyfriend. There are all these kinds of connections, and I heard all these Frank O’Hara stories at dinner. Between the poetry and the life stories and impact on these people—I thought this is very powerful.

Claude Peck is a writer and editor who lives in Minneapolis and Palm Springs.