LANGSTON HUGHES

LANGSTON HUGHES

by W. Jason Miller

Reaktion Books. 224 pages, $19.

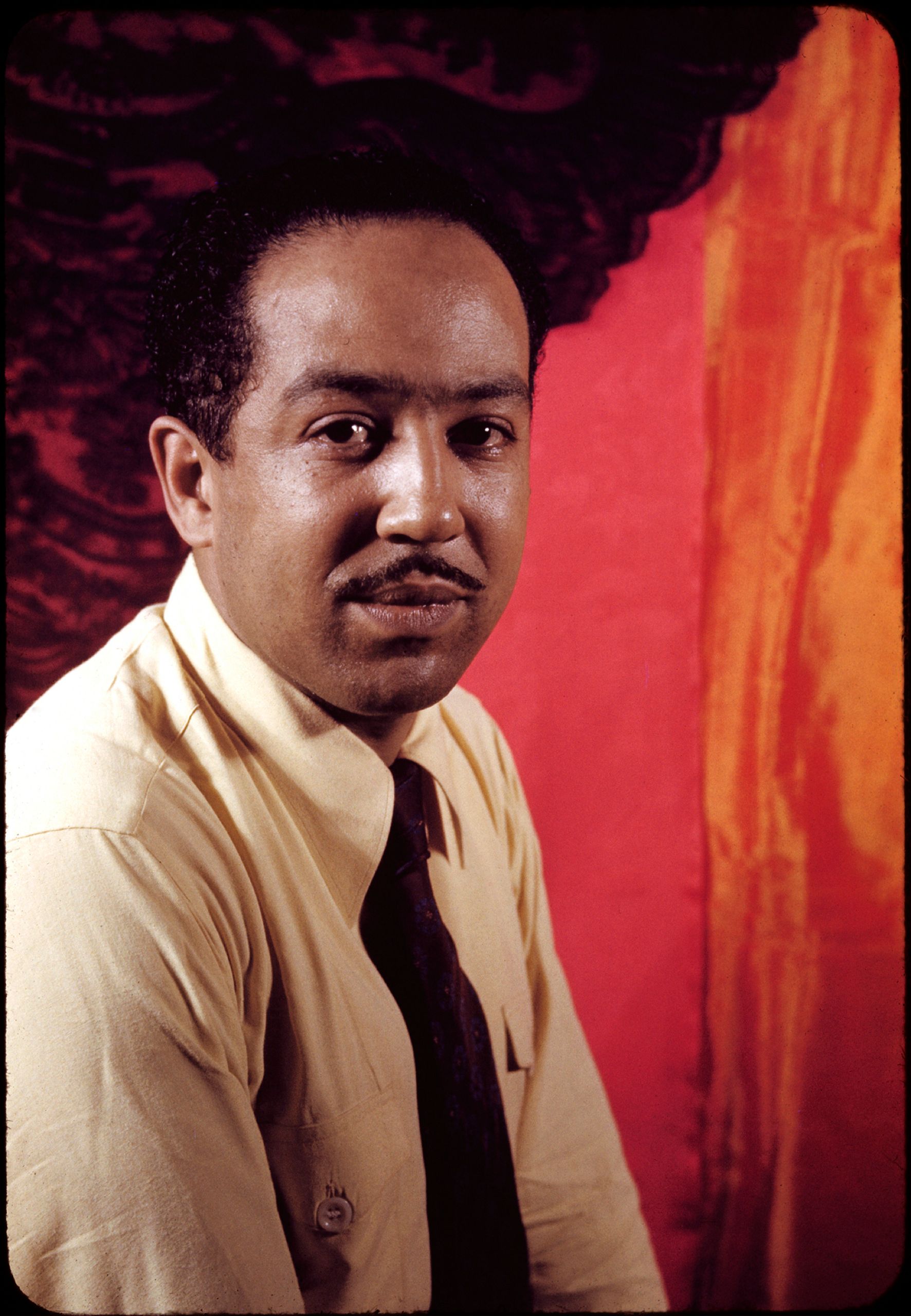

LANGSTON HUGHES (1902–1967), one of the best-known writers of the Harlem Renais-sance, remains an endlessly fascinating, charismatic figure. He was born into a chaotic but well-educated and politically connected family, sometimes living with his mother or grandmother or family friends. At other times, usually during the summer, he lived with his father, who could abide neither family life nor Jim Crow laws, and had left his family behind to build a life in Mexico. This unsettled life no doubt was part of the reason that Hughes wrote in his second memoir, I Wonder as I Wander (1956): “I often feel very sad inside myself [though]not inclined to show it.” He was elected class poet in elementary school, where his teachers introduced him to such poets as Carl Sandburg, Amy Lowell, and Walt Whitman. But it was after reading the poems of Guy de Maupassant that he decided to become a poet.

W. Jason Miller, a professor of literature at North Carolina State University, has chosen to concentrate on close readings of Hughes’ poetry, noting how far ahead of its time it seemed, and the fact that Hughes frequently requested that a blues musician provide accompaniment when he gave poetry readings. Because this is not a comprehensive biography, it’s not the place to find out about Hughes’ intimate relationships, whether male or female. In fact, Miller wonders why Hughes “was so guarded about his sexuality.” He mentions Hughes’ 1951 poem “Café: 3 a.m.” as one that “addresses homosexuality” sympathetically.

Miller states that Hughes was the first African-American writer to make a living exclusively from his writing, though it was a very tenuous living. In his younger years, he worked as a seaman on trans-Atlantic ships, which he wrote about in his first memoir, The Big Sea (1940). He referred without comment to a cabinmate, a Puerto Rican sailor who “didn’t care much for women” and preferred silk stockings, which “he bought on the African coast and slept with under his pillow.” Hughes was hired by the Baltimore Afro-American to report from the front lines of the Spanish Civil War, and he traveled all over the U.S. to give readings in far-flung locations. He was generous to a fault with his brother and mother, with whom he had a fraught relationship, and he spent a good deal subsidizing their lives.

It was in Russia in the 1930s that he received the most money for his writing, but he wrote: “Once I gave as my reason for not joining the Party the fact that jazz was officially taboo in Russia. ‘It’s my music,’ I said, ‘and I wouldn’t give up jazz for a world revolution.’” Hughes’ dedication to music was such that he always traveled with his 78 rpm records and a portable gramophone, cutting-edge technology at the time. On returning to the U.S., he created his own theater, Harlem Suitcase Theater, which Miller notes was based on “Russian experimental techniques.” Few props and costumes meant that shows could easily go on the road.

This is a physically attractive book, with heavy, glossy pages and some rarely seen black-and-white images, but it seems to have been rushed into production, with numerous misspellings and at least one very glaring error. Hughes was not the first African-American to have had a script purchased by Hollywood. That honor, at least as far as can be ascertained, goes to fellow Harlem Renaissance writer Wallace Thurman, who sold two scripts to the “B” unit of Warner Brothers shortly before his death at age 32 in 1934, five years before Hughes’ co-authored the script for Way Down South.

Martha Stone is the literary editor of this magazine.