Editor’s Note: The following is by a grant recipient in a program launched last year by The G&LR, our Writers and Artists Grant, which was awarded to three recipients in 2023. The purpose of this grant is to assist advanced students engaged in LGBT-related research, and recipients are expected to produce an article for this magazine as part of their project. This is the first such article to appear.

REVOLUTIONARY lesbian activists in the 1980s and ’90s formed political organizations and published abolitionist material against the incarceration state, and were themselves imprisoned for their political actions. One organization dedicated to political prisoners was Out of Control: Lesbian Committee to Support Women Political Prisoners. While OOC was primarily a lesbian group in solidarity with women political prisoners, they supported freedom for all political prisoners and published several interviews with incarcerated activists through their newsletter Out of Time. According to Angela Davis, who was herself a formerly incarcerated abolitionist, OOC was “part of a large anti-carceral feminist movement that is still generally unacknowledged.”

That being the case, let us shine a light on some of the lesbian activists who participated in this movement and explore how the OOC and two other revolutionary lesbian organizations—Revolting Lesbians and Queers United in Support of Political Prisoners (quisp)—organized against the carceral state. By raising awareness about lesbian political prisoners in the U.S., these activists sought to redirect the mainstream LGBT movement from assimilationist goals to those of combating imperialism and ending mass incarceration.

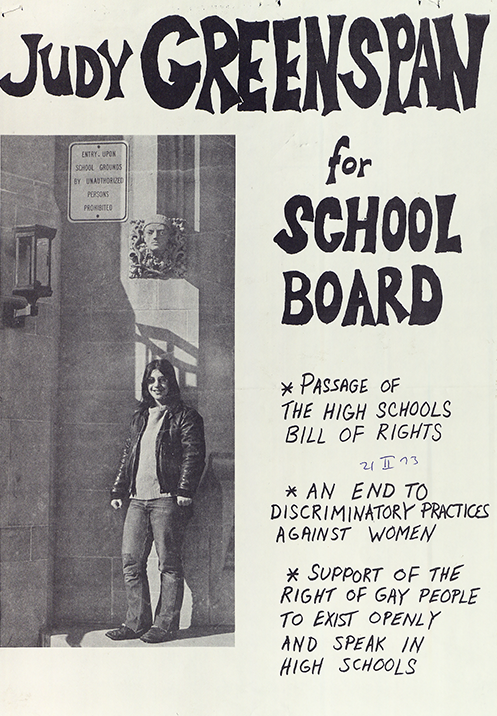

I began this project in 2018 after reading through gay and lesbian newspapers that circulated among incarcerated queer people from the 1970s to the 1990s. I kept coming across an activist named Judy Greenspan, who spent decades organizing with incarcerated people, particularly those with hiv/aids. While doing research at New York’s LGBT Community Center, an archivist suggested that Greenspan, who was in the process of donating their papers, might be willing to speak with me. Through Greenspan’s connections, I began collecting oral histories with Laura Whitehorn, Linda Evans, and Eve Rosahn—all lesbian revolutionaries and antecedents of the prison abolition movement. Years later, this network of activists remains loosely connected and firmly dedicated to the liberation of all oppressed people.

Cait Parker is a doctoral candidate in American Studies with a concentration in Women, Gender, & Sexuality at Purdue University.