Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima

by Damian Flanagan

Reaktion Books. 256 pages, $16.95

YUKIO MISHIMA lived—and died—with high drama. He was a prodigiously talented, prolific, and versatile writer, publishing his first story at age sixteen and writing almost continuously up to the day of his death (a very public suicide) in 1970. When he was only 28 he had already written enough for one Japanese publisher to bring out his Collected Works in six volumes, making him the youngest author ever to achieve that landmark. He would go on to write much more, of course, and in the process he’d become Japan’s first internationally famous author. He was also a celebrity playboy, cultivating romances with many prominent and well-to-do young women, throwing lavish society parties, traveling the world, championing outlandish military schemes—all the while avidly, and for the most part furtively, pursuing gay sex.It is no wonder that Mishima’s life has inspired numerous books and films.

John Nathan and Henry Scott Stokes, who knew Mishima personally, both published biographies of the writer in 1974. Paul Schrader’s 1985 biopic, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, with a soundtrack by Philip Glass, received broad critical acclaim. Jerry Piven’s The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima (2004) attempts a psychoanalytical reading of Mishima. Much more has been published in Japan. In 2013, Stone Bridge Press brought out a translation of Naoki Inose’s 1995 biography under the title Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima. At nearly 900 pages, Persona is by far the most comprehensive account of Mishima’s life. Damian Flanagan’s biography, recently published as part of the Critical Lives series issued by Reaktion Books, is compact by comparison and serves as an excellent introduction to Mishima’s life and work.

Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka (the pen name came later) in Tokyo in 1925. He lived in the house his parents shared with his maternal grandparents, a fact that figured strongly in his development. He was a small, sickly child, and his grandmother doted on him, even insisting that he remain with her when his parents eventually moved into a house of their own. After her death, he returned to his parents, and his mother became the focus of his affection. His father, unhappy with Mishima’s delicate nature and artistic sensibility, bullied him, destroying all of his early manuscripts in an attempt to dissuade him from writing. But Mishima continued his literary efforts, and when he published his first fiction, a short story in a literary magazine, he took the pen name Yukio Mishima, creating an alter ego that was as much a creation as his fiction.

In accord with his father’s wishes, Mishima studied law at Tokyo University and then began work in Japan’s Ministry of Finance, landing a prestigious position reserved for the best and the brightest. He continued to write, publishing his first novel, The Thieves, in 1948. But it was his autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Mask, published just one year later, that earned him fame and recognition. In it, he dealt frankly, even shockingly, with his homosexual feelings. The novel includes the famous scene in which the young narrator masturbates over a reproduction of St. Sebastian by the Italian Renaissance painter Guido Reni, spilling his semen upon the pages of one of his father’s expensive art books.

In accord with his father’s wishes, Mishima studied law at Tokyo University and then began work in Japan’s Ministry of Finance, landing a prestigious position reserved for the best and the brightest. He continued to write, publishing his first novel, The Thieves, in 1948. But it was his autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Mask, published just one year later, that earned him fame and recognition. In it, he dealt frankly, even shockingly, with his homosexual feelings. The novel includes the famous scene in which the young narrator masturbates over a reproduction of St. Sebastian by the Italian Renaissance painter Guido Reni, spilling his semen upon the pages of one of his father’s expensive art books.

Flanagan portrays Mishima as a driven, disciplined writer who worked hard not only at his craft but also at reinventing himself. He also provides an ongoing analysis of the writer’s strange, powerful, and lifelong homoerotic death wish, an obsession epitomized by his morbid fascination with the St. Sebastian-like martyr, who is both beautiful and heroic. Mishima’s Confessions confused readers at first, but praise from the literary elite, along with extensive media coverage, made it a bestseller. Despite its salacious subject matter, his parents were unconcerned—they dismissed the homosexual content as a ruse. (He returned to gay subjects with his 1951 novel, Forbidden Colours, and even wrote an SM/seppuku-themed porn story for the gay magazine Adonis in 1968.)

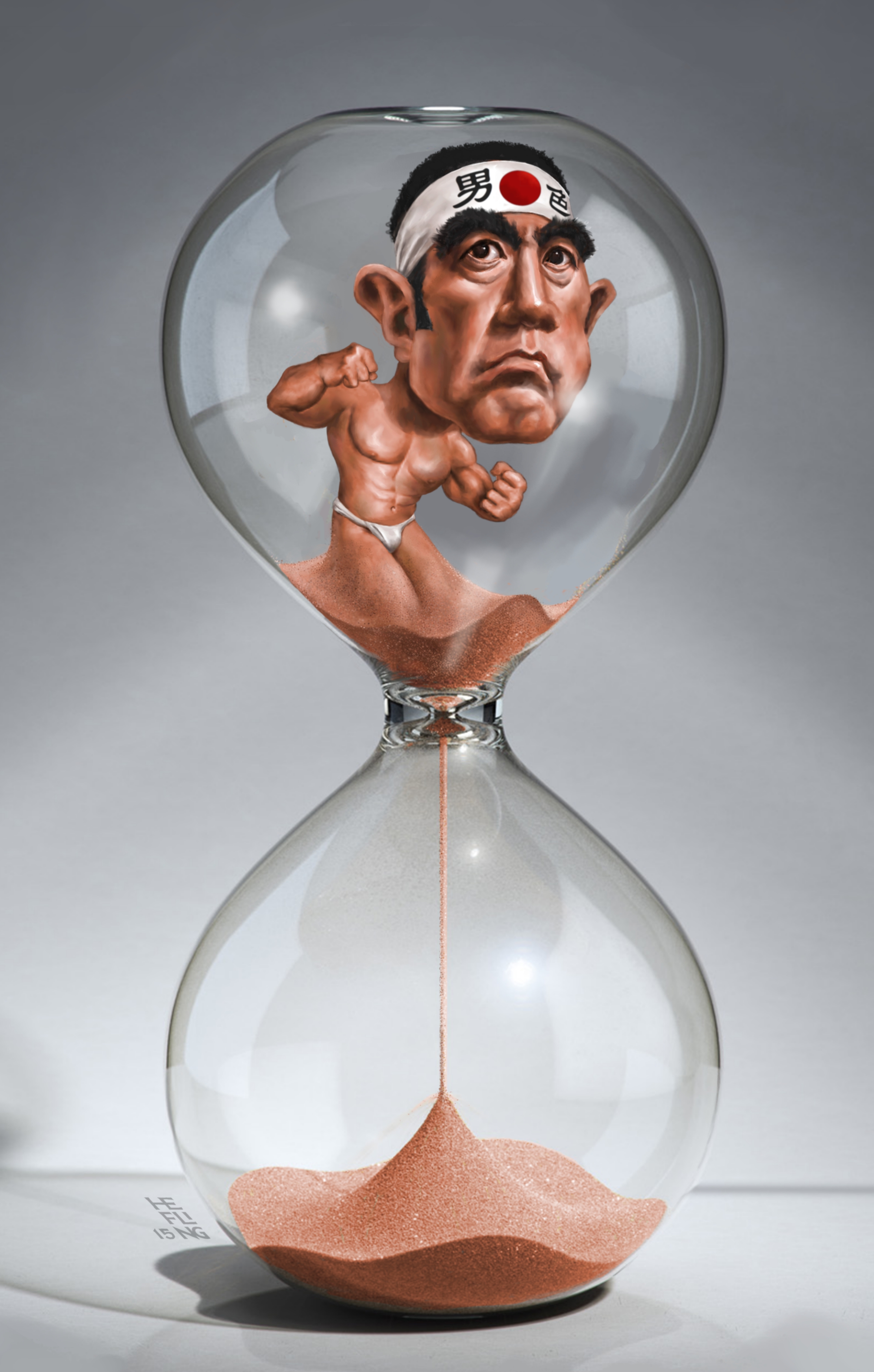

By the 1950s, Mishima was an established writer, producing a steady stream of work that included both popular, crowd-pleasing fiction (many of these novels were turned into films) and highly regarded literary works, including not only novels, but plays, short stories, and essays. He toured the world in the early 1950s and visited the U.S. not long after that, spending time with Christopher Isherwood, James Merrill, and Tennessee Williams, among others. It was during this period that he also began his obsession with bodybuilding and was often photographed honing his physique in gyms.

Mishima seems to have lived life at an almost manic pace, filling his day hours with his many social events and leaving the late night and early morning hours for his writing. In Flanagan’s analysis, Mishima was obsessed with controlling time; he considered all deadlines sacrosanct. He had a near fetish for clocks and watches, a fascination that began when the Emperor presented him with a silver watch in recognition for graduating from the Peers’ School at the top of his class in 1944. He was even known to end friendships with those who showed up late for meetings and social dates.

It’s fair to say that Mishima, like Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Knut Hamsun, is known as much for his politics as for his writing, though in Mishima’s case politics is perhaps not quite the right word. Céline and Hamsun’s achievements will be forever clouded by their anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi views. And while Mishima toyed with right-wing militarism and even wrote a play called My Friend Hitler, he was no Nazi. His patriotic, militaristic fervor was less about ideology than about his sexually motivated desire to die as a soldier in battle alongside handsome young men. He brought that desire to fruition, in 1970, committing seppuku (hara-kiri) during his carefully staged takeover of a military facility in Tokyo.

Flanagan provides deft plot summaries and sensitive readings of Mishima’s fiction and deploys a wide array of Japanese sources currently unavailable in English, producing a rich portrait of this very strange and complicated man. As Flanagan tells it, Mishima’s life was one long, extreme, calculated performance, and that assessment seems apt. It’s a performance that, 45 years later, continues to reverberate in Japan, and beyond.

Jim Nawrocki is a writer based in San Francisco.